Tuesday, February 28, 2006

ESDC: terrorism not part of Environmental Impact Statement

Ok, this isn't new, given that the discussion happened four months ago, but it's news because it hasn't been reported before: The Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), which in perhaps a month will issue a Draft Environmental Impact Statement regarding the Atlantic Yards plan, will not go beyond its legal mandate to consider terrorism as a separate issue.

On 10/24/05, even before the comment period on the Draft Scope of Analysis had closed, ESDC officials met with Brooklyn elected officials and others in the first session of Borough Board Atlantic Yards Committee.

I wasn't there and the recently-posted notes are terse, but here it is:

Will terrorism be taken into consideration as part of the EIS?

No. It is not in the scope of the EIS, but ESDC heard this recommendation at the public hearing.

Thus, the ESDC apparently won't heed the requests of the Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods and community boards to consider terrorism, an issue I wrote about before the 10/24/05 notes were posted.

That's not to say that the New York Police Department won't evaluate security issues, as it's been asked to do--though the report hasn't yet been released). But the law governing the EIS--which was written, of course, before the 9/11 attacks raised public consciousness about terrorism--doesn't require the state to do so.

As with the ESDC's close relationship with developers, which is part of its mission, the statute governing the scope of the EIS might deserve another look.

On 10/24/05, even before the comment period on the Draft Scope of Analysis had closed, ESDC officials met with Brooklyn elected officials and others in the first session of Borough Board Atlantic Yards Committee.

I wasn't there and the recently-posted notes are terse, but here it is:

Will terrorism be taken into consideration as part of the EIS?

No. It is not in the scope of the EIS, but ESDC heard this recommendation at the public hearing.

Thus, the ESDC apparently won't heed the requests of the Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods and community boards to consider terrorism, an issue I wrote about before the 10/24/05 notes were posted.

That's not to say that the New York Police Department won't evaluate security issues, as it's been asked to do--though the report hasn't yet been released). But the law governing the EIS--which was written, of course, before the 9/11 attacks raised public consciousness about terrorism--doesn't require the state to do so.

As with the ESDC's close relationship with developers, which is part of its mission, the statute governing the scope of the EIS might deserve another look.

Saturday, February 25, 2006

An alternative to Ratner's CBA? Development groups work toward new principles

Was the Atlantic Yards plan just a few years too soon for economic development groups to get organized? That's one conclusion from Mark Winston Griffith's article Redefining Economic Development in the February Gotham Gazette.

Griffith wrote:

A fledgling coalition of some of the most prominent economic development groups in the city have been meeting over the last year to create a blueprint that offers a comprehensive and alternative vision of what development should look like in the Bloomberg era. “Re-Defining Economic Development” -- or RED NY, as this coalition’s efforts are called -- began as an attempt to make new development projects in the city more accountable. Its participants all have the conviction that New York’s prosperity should be shared more broadly throughout the city.

While the Atlantic Yards plan was announced in December 2003, RED NY's precursors began in the following year:

The roots of Re-Defining New York go back to a series of meetings in 2004 -– the Subsidy Accountability Strategy Session -- that were put together by Jobs with Justice New York, a group that organizes to support the rights of workers and increase their standard of living. At these meetings more than 40 organizations, including the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, Good Jobs New York and the Pratt Center for Community Development, attempted to figure out how to demand more public benefit from projects that received incentives and subsidies from the city and state coffers.

It took more than a year to reconstitute the group:

[A]t a meeting in November of 2005, Jobs with Justice, along with Good Jobs and Pratt, again invited dozens of activists to participate in a series of meetings, this time called Re-Defining Economic Development (RED NY).

Since the November meeting of RED NY, a working group consisting of more than a dozen organizations has emerged to establish a set of principles that could possibly be “endorsed” by a broad range of organizing and advocacy groups in the city. One suggestion is that these principles could then be used to judge the candidates for governor, and encourage them to adopt a progressive platform on economic development. RED NY is also organizing training sessions designed to help people from different economic development disciplines establish common ground and a common understanding of the issues.

Atlantic Yards alternatives?

The principles developed could have had consequences for the Atlantic Yards plan:

But Michelle de la Uz, executive director of the Fifth Avenue Committee, is very clear on the practical uses for a new economic development blueprint. The Fifth Avenue Committee is one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit to stop Bruce Ratner from demolishing six buildings en route to building the Nets stadium and hundreds of commercial and residential units over Atlantic Yards in downtown Brooklyn.

(Note that Atlantic Yards not a place but a project that includes the MTA's Vanderbilt Yards, and it's near downtown.)

While the developer Forest City Ratner and eight community groups, several of them with no track record, negotiated a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA), that has been widely criticized. But it was the city's first CBA, and there were no standards. As Griffiths wrote:

What de la Uz envisions is a set of standards for job creation, environmental impact, buy-in from the surrounding area, etc. that the city or a private developer could be held to whenever they planned to use public resources. In her opinion such a standard would have set a much higher bar for Ratner to clear before he was able to pursue the Nets Arena project. The surrounding neighborhood, in de la Uz’s opinion, would have had “real” community benefit “guarantees” instead of what she considers to be the highly questionable and unenforceable promises for job creation and affordable housing that Ratner was able to negotiate.

Griffith wrote:

A fledgling coalition of some of the most prominent economic development groups in the city have been meeting over the last year to create a blueprint that offers a comprehensive and alternative vision of what development should look like in the Bloomberg era. “Re-Defining Economic Development” -- or RED NY, as this coalition’s efforts are called -- began as an attempt to make new development projects in the city more accountable. Its participants all have the conviction that New York’s prosperity should be shared more broadly throughout the city.

While the Atlantic Yards plan was announced in December 2003, RED NY's precursors began in the following year:

The roots of Re-Defining New York go back to a series of meetings in 2004 -– the Subsidy Accountability Strategy Session -- that were put together by Jobs with Justice New York, a group that organizes to support the rights of workers and increase their standard of living. At these meetings more than 40 organizations, including the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, Good Jobs New York and the Pratt Center for Community Development, attempted to figure out how to demand more public benefit from projects that received incentives and subsidies from the city and state coffers.

It took more than a year to reconstitute the group:

[A]t a meeting in November of 2005, Jobs with Justice, along with Good Jobs and Pratt, again invited dozens of activists to participate in a series of meetings, this time called Re-Defining Economic Development (RED NY).

Since the November meeting of RED NY, a working group consisting of more than a dozen organizations has emerged to establish a set of principles that could possibly be “endorsed” by a broad range of organizing and advocacy groups in the city. One suggestion is that these principles could then be used to judge the candidates for governor, and encourage them to adopt a progressive platform on economic development. RED NY is also organizing training sessions designed to help people from different economic development disciplines establish common ground and a common understanding of the issues.

Atlantic Yards alternatives?

The principles developed could have had consequences for the Atlantic Yards plan:

But Michelle de la Uz, executive director of the Fifth Avenue Committee, is very clear on the practical uses for a new economic development blueprint. The Fifth Avenue Committee is one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit to stop Bruce Ratner from demolishing six buildings en route to building the Nets stadium and hundreds of commercial and residential units over Atlantic Yards in downtown Brooklyn.

(Note that Atlantic Yards not a place but a project that includes the MTA's Vanderbilt Yards, and it's near downtown.)

While the developer Forest City Ratner and eight community groups, several of them with no track record, negotiated a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA), that has been widely criticized. But it was the city's first CBA, and there were no standards. As Griffiths wrote:

What de la Uz envisions is a set of standards for job creation, environmental impact, buy-in from the surrounding area, etc. that the city or a private developer could be held to whenever they planned to use public resources. In her opinion such a standard would have set a much higher bar for Ratner to clear before he was able to pursue the Nets Arena project. The surrounding neighborhood, in de la Uz’s opinion, would have had “real” community benefit “guarantees” instead of what she considers to be the highly questionable and unenforceable promises for job creation and affordable housing that Ratner was able to negotiate.

Friday, February 24, 2006

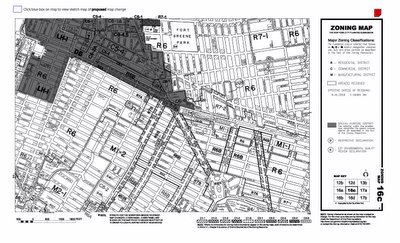

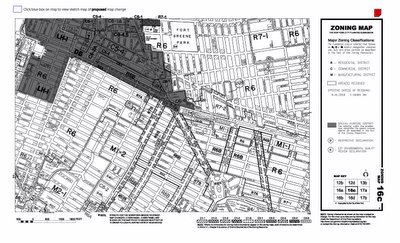

Zoning stasis (for 45 years), the local downzoning push, and the Atlantic Yards bypass

Development in New York is usually shaped by zoning--though the state would override city zoning for the Atlantic Yards project--and the building boom around the city has caused local officials and neighborhood activists to wake up. "For the most part, the zoning we have in New York is from 1961," Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society, recently told the real estate monthly The Real Deal. "That rezoning was based on the expectation that the city's population would double over the next 40 years, which hasn't come close to happening."

For example, parts of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, have R6 zoning. As the Fort Greene Association (FGA) has pointed out, a typical R6 development is between three and 12 stories. While the zoning code supports "construction of tall, slender buildings surrounded by large, open spaces," the FGA would prefer more contexual buildings that produce similar square footage but cover larger portions of the lots, under R6B zoning. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) in R6 districts ranges from 0.78 to 2.43, while R6B would have an FAR of 2.0. (Remember, the FAR for the Atlantic Yards project would be much larger, from 9.5 to 12, depending on how it's calculated, according to architect Jonathan Cohn.)

For example, parts of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, have R6 zoning. As the Fort Greene Association (FGA) has pointed out, a typical R6 development is between three and 12 stories. While the zoning code supports "construction of tall, slender buildings surrounded by large, open spaces," the FGA would prefer more contexual buildings that produce similar square footage but cover larger portions of the lots, under R6B zoning. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) in R6 districts ranges from 0.78 to 2.43, while R6B would have an FAR of 2.0. (Remember, the FAR for the Atlantic Yards project would be much larger, from 9.5 to 12, depending on how it's calculated, according to architect Jonathan Cohn.)

The response: downzoning

As noted by The Real Deal, in the article headlined Looking for an upside to downzoning, the local backlash has led to new zoning restrictions on building heights and density in neighborhoods such as Bensonhurst, South Park Slope, and Bay Ridge. (This is separate from the rezoning to spur development in Williamsburg/Greenpoint and elsewhere.) "The key phrase invoked with these rules is 'preservation of the existing character of the neighborhood,'" the article stated.

At a panel 2/21/06 organized by the Historic Districts Council, titled "Neighborhood Preservation in Brooklyn: Preserving the Past, Planning the Future," several people pointed to the rapid change and the belated response. "Brooklyn has been complacent," observed architectural historian Andrew Dolkart, who noted that the last sizable historic district in Brooklyn was established in 1982. "If nothing else good comes out of Atlantic Yards," he said, "it will be that people have woken up to the fact" that they must much more closely consider the built environment.

Dolkart pointed to efforts to add blocks to the Fort Greene and Clinton Hill historic districts, and the need to preserve Wallabout, the area between Myrtle Avenue and the Brooklyn Navy Yard. (Note that the panel specifically aimed not to address the Atlantic Yards project.)

It's political

Asked what role politics should play in community preservation, Aaron Brashear of the Concerned Citizens of Greenwood Heights commented, "In our case, very heavily." He said his group lobbied the local community board, elected officials, and the city planning office: "We were fortunate there weren't too many developers in our neighborhood with their hands in political pockets."

"We live in a democracy," said Winston Von Engel, of the Department of City Planning. "You can use political pressure and reason. Zoning changes usually come from the grassroots." A question for those watching the Atlantic Yards project remains: how much leverage does the public have in a state process that overrides zoning and is supervised by the Empire State Development Corporation?

For example, parts of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, have R6 zoning. As the Fort Greene Association (FGA) has pointed out, a typical R6 development is between three and 12 stories. While the zoning code supports "construction of tall, slender buildings surrounded by large, open spaces," the FGA would prefer more contexual buildings that produce similar square footage but cover larger portions of the lots, under R6B zoning. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) in R6 districts ranges from 0.78 to 2.43, while R6B would have an FAR of 2.0. (Remember, the FAR for the Atlantic Yards project would be much larger, from 9.5 to 12, depending on how it's calculated, according to architect Jonathan Cohn.)

For example, parts of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, have R6 zoning. As the Fort Greene Association (FGA) has pointed out, a typical R6 development is between three and 12 stories. While the zoning code supports "construction of tall, slender buildings surrounded by large, open spaces," the FGA would prefer more contexual buildings that produce similar square footage but cover larger portions of the lots, under R6B zoning. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) in R6 districts ranges from 0.78 to 2.43, while R6B would have an FAR of 2.0. (Remember, the FAR for the Atlantic Yards project would be much larger, from 9.5 to 12, depending on how it's calculated, according to architect Jonathan Cohn.)The response: downzoning

As noted by The Real Deal, in the article headlined Looking for an upside to downzoning, the local backlash has led to new zoning restrictions on building heights and density in neighborhoods such as Bensonhurst, South Park Slope, and Bay Ridge. (This is separate from the rezoning to spur development in Williamsburg/Greenpoint and elsewhere.) "The key phrase invoked with these rules is 'preservation of the existing character of the neighborhood,'" the article stated.

At a panel 2/21/06 organized by the Historic Districts Council, titled "Neighborhood Preservation in Brooklyn: Preserving the Past, Planning the Future," several people pointed to the rapid change and the belated response. "Brooklyn has been complacent," observed architectural historian Andrew Dolkart, who noted that the last sizable historic district in Brooklyn was established in 1982. "If nothing else good comes out of Atlantic Yards," he said, "it will be that people have woken up to the fact" that they must much more closely consider the built environment.

Dolkart pointed to efforts to add blocks to the Fort Greene and Clinton Hill historic districts, and the need to preserve Wallabout, the area between Myrtle Avenue and the Brooklyn Navy Yard. (Note that the panel specifically aimed not to address the Atlantic Yards project.)

It's political

Asked what role politics should play in community preservation, Aaron Brashear of the Concerned Citizens of Greenwood Heights commented, "In our case, very heavily." He said his group lobbied the local community board, elected officials, and the city planning office: "We were fortunate there weren't too many developers in our neighborhood with their hands in political pockets."

"We live in a democracy," said Winston Von Engel, of the Department of City Planning. "You can use political pressure and reason. Zoning changes usually come from the grassroots." A question for those watching the Atlantic Yards project remains: how much leverage does the public have in a state process that overrides zoning and is supervised by the Empire State Development Corporation?

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

A Times roundup on eminent domain: no mention of Brooklyn or the newspaper's own history

The New York Times offers a front-page article on eminent domain today, headlined States Curbing Right to Seize Private Homes. It's one of those national roundups, covering a lot of bases, with a nod to issues in the tristate area. There's no mention of the Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn or the parent Times Company's own use of eminent domain.

There's a finite amount of space for such an article, so it's a judgment call about what to include. And the New York Times is a national newspaper. Still, its center of gravity is New York City, and there's a strong case that even roundup articles should mention its home city where eminent domain is at issue--such as the Atlantic Yards project. Perhaps this is caused by balkanization of coverage. As noted in Chapter 9 of my report, the national desk's coverage of the Supreme Court's Kelo decision--the ruling that sparked the new state legislation discussed today--neglected the local angle.

[Update: a reader comments that the reporter was writing a roundup of state legislative efforts, not the eminent domain issue in general, so the failure to mention the Brooklyn issue was defensible. Yes, I should've been more precise. Still, the article did mention some the impact of state reforms on some specific projects: a new stadium for the Dallas Cowboys, a Texas highway project, and a case in the Cincinnati suburb of Norwood. The issue in Brooklyn may not be as prominent in New York, relatively speaking, as the other cases mentioned are in their states. Then again, the Times should think of its local readers as well.]

There's also a case that the Times should disclose its own corporate role; it has not done so regularly but did in a 1/26/06 article (from the business/financial desk) headlined Bank to Deny Loans if Land Was Seized: "The New York Times Company used eminent domain to acquire the land for its new headquarters under construction in Midtown." [Addendum: After some discussion, I'll suggest that it is a judgment call, and the case is strongest when the Times is writing about the use of eminent domain in New York--which was not the subject of this article.]

Today's article included these passages:

The issue was one of the first raised when Connecticut lawmakers returned to session early this month. There are bills pending in the Legislature to impose new restrictions on the use of eminent domain by local governments and to assure that displaced businesses and homeowners receive fair compensation.

(The New London project is essentially delayed, even after the Supreme Court go-ahead, because of contractual disputes and an unwillingness to forcibly remove the homeowners who sued to save their properties.)

In the New Jersey Legislature, Senator Nia H. Gill, a Democrat from Montclair who is chairwoman of the Commerce Committee, proposed a bill to outlaw the use of eminent domain to condemn residential property that is not completely run down to make room for a redevelopment project. The bill, which is pending, would require public hearings before any taking of private property to benefit a private project.

In New York, State Senator John A. DeFrancisco, a Republican, has proposed a measure similar to one in other states that would remove the right to exercise condemnation power from unelected bodies like an urban redevelopment authority or an industrial development agency.

There's a finite amount of space for such an article, so it's a judgment call about what to include. And the New York Times is a national newspaper. Still, its center of gravity is New York City, and there's a strong case that even roundup articles should mention its home city where eminent domain is at issue--such as the Atlantic Yards project. Perhaps this is caused by balkanization of coverage. As noted in Chapter 9 of my report, the national desk's coverage of the Supreme Court's Kelo decision--the ruling that sparked the new state legislation discussed today--neglected the local angle.

[Update: a reader comments that the reporter was writing a roundup of state legislative efforts, not the eminent domain issue in general, so the failure to mention the Brooklyn issue was defensible. Yes, I should've been more precise. Still, the article did mention some the impact of state reforms on some specific projects: a new stadium for the Dallas Cowboys, a Texas highway project, and a case in the Cincinnati suburb of Norwood. The issue in Brooklyn may not be as prominent in New York, relatively speaking, as the other cases mentioned are in their states. Then again, the Times should think of its local readers as well.]

There's also a case that the Times should disclose its own corporate role; it has not done so regularly but did in a 1/26/06 article (from the business/financial desk) headlined Bank to Deny Loans if Land Was Seized: "The New York Times Company used eminent domain to acquire the land for its new headquarters under construction in Midtown." [Addendum: After some discussion, I'll suggest that it is a judgment call, and the case is strongest when the Times is writing about the use of eminent domain in New York--which was not the subject of this article.]

Today's article included these passages:

The issue was one of the first raised when Connecticut lawmakers returned to session early this month. There are bills pending in the Legislature to impose new restrictions on the use of eminent domain by local governments and to assure that displaced businesses and homeowners receive fair compensation.

(The New London project is essentially delayed, even after the Supreme Court go-ahead, because of contractual disputes and an unwillingness to forcibly remove the homeowners who sued to save their properties.)

In the New Jersey Legislature, Senator Nia H. Gill, a Democrat from Montclair who is chairwoman of the Commerce Committee, proposed a bill to outlaw the use of eminent domain to condemn residential property that is not completely run down to make room for a redevelopment project. The bill, which is pending, would require public hearings before any taking of private property to benefit a private project.

In New York, State Senator John A. DeFrancisco, a Republican, has proposed a measure similar to one in other states that would remove the right to exercise condemnation power from unelected bodies like an urban redevelopment authority or an industrial development agency.

Monday, February 20, 2006

Demolitions timeline: what do "emergency" and "immediate" mean?

What did they know and when did they know it? Did Forest City Ratner act responsibly in its plans to demolish several buildings it owns or controls? Did the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC)?

The testimony and legal filings in the court case filed by Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) and other community groups, in which state Supreme Court Justice Carol Edmead refused to overturn ESDC's approval of the demolition plans, offer a timeline to flesh out some of those questions.

The papers suggest that the terms "emergency" and "immediate" may be legal terms required to approve the demolitions, but at the same time, the actions of the parties belie the urgency suggested by the plain meaning of those terms. Otherwise, the parties might have acted more quickly and tried harder to warn the public.

In Spring 2005, Forest City Ratner was advised to apply to the ESDC to demolish the buildings as an "emergency." However, the company did not, for various reasons, make the effort for several months. On 11/7/05, LZA Technology, a respected engineering firm hired by the developer, certified that 11 buildings at five properties were in "immediate" danger. But it took the ESDC five weeks to approve the decision; during that interregnum, there was no apparent effort by the developer to warn the public.

That's not to say that Forest City Ratner has tried to knock down most of the buildings it has acquired. Indeed, a company official said in his affidavit that the developer deferred to the judgment of its consultant and withdrew plans to demolish buildings that were deemed structurally sound.

Winter 2004-05: plans emerge

According to Forest City Ratner's contract for demolition work with Gateway Demolition Corp., the environmental firm AKRF--the same firm that is now working for the ESDC--conducted environmental site assessments in April, June, and August of 2004. But the real path toward the demolitions began at the end of the year. In December, 2004, contractors conducted asbestos inspection report for the Underberg Building, at 608-620 Atlantic Avenue. (Photo by Forgotten NY.)

According to Forest City Ratner's contract for demolition work with Gateway Demolition Corp., the environmental firm AKRF--the same firm that is now working for the ESDC--conducted environmental site assessments in April, June, and August of 2004. But the real path toward the demolitions began at the end of the year. In December, 2004, contractors conducted asbestos inspection report for the Underberg Building, at 608-620 Atlantic Avenue. (Photo by Forgotten NY.)

In January or February 2005, according to an affidavit from FCR's Andrew Zlotnick, in consultation with environmental consultants at AKRF, he put together a list of buildings that appared to be so dilapidated that they would require demolition rather than maintenance. Besides consulting with staff members, the company also retained LZA Technology, "a well-known Manhattan based firm of consulting structural engineers."

According to the contract, the inspections began in January, and in February and March, demolition plans were drawn up for several buildings.

1/14/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 461 Dean Street

1/16/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 463 Dean Street

2/05: Environmental site assessments

2/10/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 585-601 Dean Street

2/15/05: Demolition specifications for 608-620 Atlantic Avenue

3/2/05: Structural due diligence survey of 461 & 463 Dean Street, and 585-601 Dean Street

3/4/05: Demolition plan for building at 585-601 Dean Street

3/7/05: Demolition plan for buildings at 461-465 Dean Street and 626 Pacific Street

Spring 2005: legal twist, MTA roadblock

Zlotnick stated: "As to some of the buildings that I had identified as potentially so hazardous as to require demolition, LZA advised me that, in its opinion, the buildings were not structurally unsound and need not be demolished. As to those

Zlotnick stated: "As to some of the buildings that I had identified as potentially so hazardous as to require demolition, LZA advised me that, in its opinion, the buildings were not structurally unsound and need not be demolished. As to those

buildings, FCRC deferred to LZA's professional judgment and decided not to proceed with demolition. Nevertheless,in the spring of 2005, FCRC had received reports from LZA recommending that six or seven buildings that FCRC had acquired or was in contract to acquire were so unsafe and structurally unsound that they should be demolished." (Right, 461 and 463 Dean Street, in a photo taken shortly after the 12/16/05 demolition announcement. There were no apparent warning signs.)

On 4/28/05, FCR issued a notice of intent to award the demolition contract and on 5/2/05, the developer listed the scope of work for demolition. However, a legal dispute arose about FCR's right to demolish the buildings. Attorney Melanie Meyers argued that FCR had the right to demolish the buildings without any ESDC review; attorney David Paget, then working for the developer (but later for ESDC), and the ESDC's Rachel Shatz said state regulations required ESDC approval. Paget suggested a solution, according to Meyers: state law exempts from the SEQRA (State Environmental Quality Act) "emergency actions that are immediately necessary on a limited and temporary basis for the protection or preservation of life, health, property or natural resources." FCR, according to Meyers, decided to submit materials to ESDC to determine that an emergency existed.

However, a roadblock arose. According to Zlotnick's affidavit, some of the structures were close to subway tunnels and could not be demolished without the MTA signing off on the process. Meyers wrote that "efforts toward demolition" halted in late spring because the Metropolitan Transportation Authority sought competitive bids for the Vanderbilt Yards. "Because of the ongoing public bidding process, there was a moratorium on any FCRC communications with the MTA and ESDC regarding the Project," she stated.

The moratorium lasted until 9/14/05, when the MTA awarded FCR the right to develop the railyard. Note that Jeffrey Baker, the attorney for Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, said in court that Bruce Ratner met twice with MTA officials, including Chairman Peter Kalikow, during that supposed interregnum.

Summer 2005: moving ahead

According to the contract, LZA continued its inspections:

6/23/05: Structural due diligence survey for 608-620 Atlantic Avenue

6/27/05 & 6/30/05: Demolition plan for buildings at 620 Pacific Street

7/6/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 620 Pacific Street

7/23/05: Structural due diligence survey for 620 Pacific Street

On 9/14/05, the MTA awarded FCR the right to develop the railyard, and thus removed the moratorium. On 9/16/05, ESDC issued a notice that it would be the lead agency for environmental review process.

Fall 2005: another look, a five-week gap

On 10/18/05, ESDC held a six-hour public scoping hearing on the project. At about the same time, FCR asked LZA to update its surveys, expressing concern that snow, ice, and other weather conditions could further damage the buildings, according to Zlotnick. On 11/2/05, a LZA engineer made a presentation, with Power Point slides, to MTA, ESDC, and FCR representatives. On 11/7/05, LZA prepared a new report on the buildings, calling their condition "an immediate threat to the preservation of life, health, and property." The next day, FCR sent the LZA report to ESDC, via FedEx. (Above, 620 and 622 Pacific Street, shortly after the 12/16/05 announcement of the demolition plans. There were no apparent warning signs.)

On 10/18/05, ESDC held a six-hour public scoping hearing on the project. At about the same time, FCR asked LZA to update its surveys, expressing concern that snow, ice, and other weather conditions could further damage the buildings, according to Zlotnick. On 11/2/05, a LZA engineer made a presentation, with Power Point slides, to MTA, ESDC, and FCR representatives. On 11/7/05, LZA prepared a new report on the buildings, calling their condition "an immediate threat to the preservation of life, health, and property." The next day, FCR sent the LZA report to ESDC, via FedEx. (Above, 620 and 622 Pacific Street, shortly after the 12/16/05 announcement of the demolition plans. There were no apparent warning signs.)

It took five weeks for the ESDC to act, but it's not clear why. The agency's Shatz said in an affidavit that there were both internal and external meetings. "After reviewing the LZA report and consulting with other senior officials at the ESDC, and our outside environmental counsel Sive Paget, I determined that an 'emergency' existed," she stated.

[Note that I wrote on 12/30/05 that "the timing of Forest City Ratner's announcement seems to have been tied less to the receipt of the report than the plans for asbestos abatement." According to the papers filed in the lawsuit, the timing related to the receipt of the ESDC's approval.]

Meanwhile, work by LZA continued, according to the contract.

11/22/05: Environmental site assessments

11/30/05: Demolition plan for building at 622 Pacific Street

On 12/1/05, FCR issued a revised scope of work for demolition, the next day revised its notice of intent to award the demolition contract. On 12/14/05, according to the contract, it again revised the scope of work for demolition.

Emergency declared

On 12/15/05, Shatz, in a memo to the ESDC's Atlantic Yards project file, concluded that "demolition of the Unsafe Structures by FCRC is an emergency action that is immediately necessary on a limited and temporary basis for the protection and preservation of life, health, and property." (The footer of the memo, curiously enough, was dated 12/5/05.) The same day, Forest City Ratner gave the New York Times an exclusive regarding its demolition plans.

On 12/16/05, ESDC sent FCR a letter declaring the demolitions to be an emergency action. The same day, when the Times story appeared, FCR issued a press release saying it would begin asbestos abatement and then demolish six buildings. (One of those buildings, 622 Pacific Street, was incorrectly listed, because LZA had not included it in its report to ESDC.) FCR also issued a demolition contract that day.

A week later, on 12/22/05, FCR again revised its notice of intent to award the demolition contract, and revised the scope of demolition work.

During the week of December 19, DDDB and local politicans asked for an opportunity to look at the buildings, with an independent engineer. Forest City Ratner initially agreed, and an inspection was scheduled for 12/20/05, including representatives of DDDB, Council Member Letitia James, and the engineer. "That inspection was cancelled by FCRC without explanation, and a subsequent inspection was scheduled for December 21st or 22nd," according to the legal filing. "However, FCRC informed DDDB that it would not be permitted to be present at the inspection and it informed Councilwoman James that she would not be permitted to bring an engineer to the inspection." James said she wouldn't visit the buildings without the engineer. "They told me that an independent review might 'slow down the process," James said.

"The question is, God forbid that a building collapses, God forbid that a falling brick hits someone in the head, or that there's a fire," FCR's Bruce Bender said, according to the 12/16/05 Times article. On the one hand, the approaching winter did present a more hazardous situation, especially since Forest City Ratner neglected to seal all the windows in its buildings. On the other hand, the concept of "emergency" had existed since the spring.

Winter 2005-06: lawsuit

In January 2006, engineer Jay Butler said in an affidavit, after reviewing the LZA report and conducting an external examination of the buildings: "Any defects to the buildings or threats to public safety appear to be consistent with conditions found at countless other buildings in New York City. Such defects can be safely stabilized with commonly-used repair measures." He acknowledged that his observations were preliminary; the LZA report said that the interiors of the structures were far more damaged than the exteriors. (Above, 585-601 Dean Street.)

In January 2006, engineer Jay Butler said in an affidavit, after reviewing the LZA report and conducting an external examination of the buildings: "Any defects to the buildings or threats to public safety appear to be consistent with conditions found at countless other buildings in New York City. Such defects can be safely stabilized with commonly-used repair measures." He acknowledged that his observations were preliminary; the LZA report said that the interiors of the structures were far more damaged than the exteriors. (Above, 585-601 Dean Street.)

On 1/18/06, DDDB and associated groups filed suit to block the demolitions and to disqualify Paget. On 2/14/06, Edmead refused to block the demolitions but did disqualify Paget. Two days later, the ESDC appealed Edmead's disqualification decision.

Note that there are five properties at issue, since a sixth building initially announced for demolition has not yet approved by the ESDC. The petitioners consider the six initially announced properties 12 buildings since one of the properties has a building behind it, and the Underberg Building is six joined structures. Subtracting that one building, five properties and 11 buildings are, according to the ESDC, approved for demolition, but Forest City Ratner must still get permits from the city Department of Buildings.

The testimony and legal filings in the court case filed by Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) and other community groups, in which state Supreme Court Justice Carol Edmead refused to overturn ESDC's approval of the demolition plans, offer a timeline to flesh out some of those questions.

The papers suggest that the terms "emergency" and "immediate" may be legal terms required to approve the demolitions, but at the same time, the actions of the parties belie the urgency suggested by the plain meaning of those terms. Otherwise, the parties might have acted more quickly and tried harder to warn the public.

In Spring 2005, Forest City Ratner was advised to apply to the ESDC to demolish the buildings as an "emergency." However, the company did not, for various reasons, make the effort for several months. On 11/7/05, LZA Technology, a respected engineering firm hired by the developer, certified that 11 buildings at five properties were in "immediate" danger. But it took the ESDC five weeks to approve the decision; during that interregnum, there was no apparent effort by the developer to warn the public.

That's not to say that Forest City Ratner has tried to knock down most of the buildings it has acquired. Indeed, a company official said in his affidavit that the developer deferred to the judgment of its consultant and withdrew plans to demolish buildings that were deemed structurally sound.

Winter 2004-05: plans emerge

According to Forest City Ratner's contract for demolition work with Gateway Demolition Corp., the environmental firm AKRF--the same firm that is now working for the ESDC--conducted environmental site assessments in April, June, and August of 2004. But the real path toward the demolitions began at the end of the year. In December, 2004, contractors conducted asbestos inspection report for the Underberg Building, at 608-620 Atlantic Avenue. (Photo by Forgotten NY.)

According to Forest City Ratner's contract for demolition work with Gateway Demolition Corp., the environmental firm AKRF--the same firm that is now working for the ESDC--conducted environmental site assessments in April, June, and August of 2004. But the real path toward the demolitions began at the end of the year. In December, 2004, contractors conducted asbestos inspection report for the Underberg Building, at 608-620 Atlantic Avenue. (Photo by Forgotten NY.)In January or February 2005, according to an affidavit from FCR's Andrew Zlotnick, in consultation with environmental consultants at AKRF, he put together a list of buildings that appared to be so dilapidated that they would require demolition rather than maintenance. Besides consulting with staff members, the company also retained LZA Technology, "a well-known Manhattan based firm of consulting structural engineers."

According to the contract, the inspections began in January, and in February and March, demolition plans were drawn up for several buildings.

1/14/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 461 Dean Street

1/16/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 463 Dean Street

2/05: Environmental site assessments

2/10/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 585-601 Dean Street

2/15/05: Demolition specifications for 608-620 Atlantic Avenue

3/2/05: Structural due diligence survey of 461 & 463 Dean Street, and 585-601 Dean Street

3/4/05: Demolition plan for building at 585-601 Dean Street

3/7/05: Demolition plan for buildings at 461-465 Dean Street and 626 Pacific Street

Spring 2005: legal twist, MTA roadblock

Zlotnick stated: "As to some of the buildings that I had identified as potentially so hazardous as to require demolition, LZA advised me that, in its opinion, the buildings were not structurally unsound and need not be demolished. As to those

Zlotnick stated: "As to some of the buildings that I had identified as potentially so hazardous as to require demolition, LZA advised me that, in its opinion, the buildings were not structurally unsound and need not be demolished. As to thosebuildings, FCRC deferred to LZA's professional judgment and decided not to proceed with demolition. Nevertheless,in the spring of 2005, FCRC had received reports from LZA recommending that six or seven buildings that FCRC had acquired or was in contract to acquire were so unsafe and structurally unsound that they should be demolished." (Right, 461 and 463 Dean Street, in a photo taken shortly after the 12/16/05 demolition announcement. There were no apparent warning signs.)

On 4/28/05, FCR issued a notice of intent to award the demolition contract and on 5/2/05, the developer listed the scope of work for demolition. However, a legal dispute arose about FCR's right to demolish the buildings. Attorney Melanie Meyers argued that FCR had the right to demolish the buildings without any ESDC review; attorney David Paget, then working for the developer (but later for ESDC), and the ESDC's Rachel Shatz said state regulations required ESDC approval. Paget suggested a solution, according to Meyers: state law exempts from the SEQRA (State Environmental Quality Act) "emergency actions that are immediately necessary on a limited and temporary basis for the protection or preservation of life, health, property or natural resources." FCR, according to Meyers, decided to submit materials to ESDC to determine that an emergency existed.

However, a roadblock arose. According to Zlotnick's affidavit, some of the structures were close to subway tunnels and could not be demolished without the MTA signing off on the process. Meyers wrote that "efforts toward demolition" halted in late spring because the Metropolitan Transportation Authority sought competitive bids for the Vanderbilt Yards. "Because of the ongoing public bidding process, there was a moratorium on any FCRC communications with the MTA and ESDC regarding the Project," she stated.

The moratorium lasted until 9/14/05, when the MTA awarded FCR the right to develop the railyard. Note that Jeffrey Baker, the attorney for Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, said in court that Bruce Ratner met twice with MTA officials, including Chairman Peter Kalikow, during that supposed interregnum.

Summer 2005: moving ahead

According to the contract, LZA continued its inspections:

6/23/05: Structural due diligence survey for 608-620 Atlantic Avenue

6/27/05 & 6/30/05: Demolition plan for buildings at 620 Pacific Street

7/6/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 620 Pacific Street

7/23/05: Structural due diligence survey for 620 Pacific Street

On 9/14/05, the MTA awarded FCR the right to develop the railyard, and thus removed the moratorium. On 9/16/05, ESDC issued a notice that it would be the lead agency for environmental review process.

Fall 2005: another look, a five-week gap

On 10/18/05, ESDC held a six-hour public scoping hearing on the project. At about the same time, FCR asked LZA to update its surveys, expressing concern that snow, ice, and other weather conditions could further damage the buildings, according to Zlotnick. On 11/2/05, a LZA engineer made a presentation, with Power Point slides, to MTA, ESDC, and FCR representatives. On 11/7/05, LZA prepared a new report on the buildings, calling their condition "an immediate threat to the preservation of life, health, and property." The next day, FCR sent the LZA report to ESDC, via FedEx. (Above, 620 and 622 Pacific Street, shortly after the 12/16/05 announcement of the demolition plans. There were no apparent warning signs.)

On 10/18/05, ESDC held a six-hour public scoping hearing on the project. At about the same time, FCR asked LZA to update its surveys, expressing concern that snow, ice, and other weather conditions could further damage the buildings, according to Zlotnick. On 11/2/05, a LZA engineer made a presentation, with Power Point slides, to MTA, ESDC, and FCR representatives. On 11/7/05, LZA prepared a new report on the buildings, calling their condition "an immediate threat to the preservation of life, health, and property." The next day, FCR sent the LZA report to ESDC, via FedEx. (Above, 620 and 622 Pacific Street, shortly after the 12/16/05 announcement of the demolition plans. There were no apparent warning signs.)It took five weeks for the ESDC to act, but it's not clear why. The agency's Shatz said in an affidavit that there were both internal and external meetings. "After reviewing the LZA report and consulting with other senior officials at the ESDC, and our outside environmental counsel Sive Paget, I determined that an 'emergency' existed," she stated.

[Note that I wrote on 12/30/05 that "the timing of Forest City Ratner's announcement seems to have been tied less to the receipt of the report than the plans for asbestos abatement." According to the papers filed in the lawsuit, the timing related to the receipt of the ESDC's approval.]

Meanwhile, work by LZA continued, according to the contract.

11/22/05: Environmental site assessments

11/30/05: Demolition plan for building at 622 Pacific Street

On 12/1/05, FCR issued a revised scope of work for demolition, the next day revised its notice of intent to award the demolition contract. On 12/14/05, according to the contract, it again revised the scope of work for demolition.

Emergency declared

On 12/15/05, Shatz, in a memo to the ESDC's Atlantic Yards project file, concluded that "demolition of the Unsafe Structures by FCRC is an emergency action that is immediately necessary on a limited and temporary basis for the protection and preservation of life, health, and property." (The footer of the memo, curiously enough, was dated 12/5/05.) The same day, Forest City Ratner gave the New York Times an exclusive regarding its demolition plans.

On 12/16/05, ESDC sent FCR a letter declaring the demolitions to be an emergency action. The same day, when the Times story appeared, FCR issued a press release saying it would begin asbestos abatement and then demolish six buildings. (One of those buildings, 622 Pacific Street, was incorrectly listed, because LZA had not included it in its report to ESDC.) FCR also issued a demolition contract that day.

A week later, on 12/22/05, FCR again revised its notice of intent to award the demolition contract, and revised the scope of demolition work.

During the week of December 19, DDDB and local politicans asked for an opportunity to look at the buildings, with an independent engineer. Forest City Ratner initially agreed, and an inspection was scheduled for 12/20/05, including representatives of DDDB, Council Member Letitia James, and the engineer. "That inspection was cancelled by FCRC without explanation, and a subsequent inspection was scheduled for December 21st or 22nd," according to the legal filing. "However, FCRC informed DDDB that it would not be permitted to be present at the inspection and it informed Councilwoman James that she would not be permitted to bring an engineer to the inspection." James said she wouldn't visit the buildings without the engineer. "They told me that an independent review might 'slow down the process," James said.

"The question is, God forbid that a building collapses, God forbid that a falling brick hits someone in the head, or that there's a fire," FCR's Bruce Bender said, according to the 12/16/05 Times article. On the one hand, the approaching winter did present a more hazardous situation, especially since Forest City Ratner neglected to seal all the windows in its buildings. On the other hand, the concept of "emergency" had existed since the spring.

Winter 2005-06: lawsuit

In January 2006, engineer Jay Butler said in an affidavit, after reviewing the LZA report and conducting an external examination of the buildings: "Any defects to the buildings or threats to public safety appear to be consistent with conditions found at countless other buildings in New York City. Such defects can be safely stabilized with commonly-used repair measures." He acknowledged that his observations were preliminary; the LZA report said that the interiors of the structures were far more damaged than the exteriors. (Above, 585-601 Dean Street.)

In January 2006, engineer Jay Butler said in an affidavit, after reviewing the LZA report and conducting an external examination of the buildings: "Any defects to the buildings or threats to public safety appear to be consistent with conditions found at countless other buildings in New York City. Such defects can be safely stabilized with commonly-used repair measures." He acknowledged that his observations were preliminary; the LZA report said that the interiors of the structures were far more damaged than the exteriors. (Above, 585-601 Dean Street.)On 1/18/06, DDDB and associated groups filed suit to block the demolitions and to disqualify Paget. On 2/14/06, Edmead refused to block the demolitions but did disqualify Paget. Two days later, the ESDC appealed Edmead's disqualification decision.

Note that there are five properties at issue, since a sixth building initially announced for demolition has not yet approved by the ESDC. The petitioners consider the six initially announced properties 12 buildings since one of the properties has a building behind it, and the Underberg Building is six joined structures. Subtracting that one building, five properties and 11 buildings are, according to the ESDC, approved for demolition, but Forest City Ratner must still get permits from the city Department of Buildings.

Saturday, February 18, 2006

ESDC appeals decision, says loss of lawyer puts Atlantic Yards project on hold

Until the decision on February 14 disqualifying a lawyer for the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) because he previously worked on the Atlantic Yards project for developer Forest City Ratner, ESDC had planned to issue the Final Scoping Document--a prelude to a Draft Environmental Impact Statement--within 30 days.

Now, with the potential loss of attorney David Paget, "the order of the court below has brought the environmental review process respecting the Atlantic Yards project--and thus the project itself--to a screeching halt, since experienced outside counsel is required for a project of this nature," said ESDC attorney Douglas Kraus in a statement filed with the appeal of Justice Carol Edmead's decision.

What about finding a new lawyer? Well, said Kraus, relatively few such qualified counsel exist, and three are already working for other parties in this case: two for Forest City Ratner and one for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. He asked for an expedited appeal "in the interest of fairness," and called for a schedule that would lead to an oral argument before the state appellate court during the week of March 6.

A factual twist in the legal case

As shown by Edmead's narrow decision upholding the ESDC's right to approve the demolitions proposed by Forest City Ratner, what's legal may remain questionable. While Edmead's disqualification of Paget may seem intuitively right to those objecting to the "collaborative" relationship between developer and state agency, it may not rest on solid legal ground. The judge herself said from the bench, "I don't doubt that the court's determination may not stand."

While the case law undoubtedly will be argued in competing memoranda of law, the memorandum initially filed by the ESDC makes the case that Edmead misread the documents in asserting that Paget was retained by ESDC in February 2005 and thus was representing both parties at the same time. Rather, Kraus argues in the memorandum, there was no such formal retainer, just the signing of a cost reiumbursement agreement, which actually occurred in February 2004.

Rather, Paget worked for Forest City Ratner through September 2005, then went to work for the state agency the next month--but never for both parties simultaneously. The issue, though, is broader: whether there is an apparent conflict of interest as well.

Edmead wrote, "The Court does not question respondents' contention that it is normal procedure for the applicant to pay for ESDC specialists. However, that does not obviate the obligation to avoid any conflict of interest"--a conflict stemming also from the "oft bottom-line, profit-making pursuits of real estate development corporations" and the "valid environmental interests of the ESDC." Since that pattern may be typical for such large development project, the appellate court must decide is whether it's inappropriate.

Now, with the potential loss of attorney David Paget, "the order of the court below has brought the environmental review process respecting the Atlantic Yards project--and thus the project itself--to a screeching halt, since experienced outside counsel is required for a project of this nature," said ESDC attorney Douglas Kraus in a statement filed with the appeal of Justice Carol Edmead's decision.

What about finding a new lawyer? Well, said Kraus, relatively few such qualified counsel exist, and three are already working for other parties in this case: two for Forest City Ratner and one for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. He asked for an expedited appeal "in the interest of fairness," and called for a schedule that would lead to an oral argument before the state appellate court during the week of March 6.

A factual twist in the legal case

As shown by Edmead's narrow decision upholding the ESDC's right to approve the demolitions proposed by Forest City Ratner, what's legal may remain questionable. While Edmead's disqualification of Paget may seem intuitively right to those objecting to the "collaborative" relationship between developer and state agency, it may not rest on solid legal ground. The judge herself said from the bench, "I don't doubt that the court's determination may not stand."

While the case law undoubtedly will be argued in competing memoranda of law, the memorandum initially filed by the ESDC makes the case that Edmead misread the documents in asserting that Paget was retained by ESDC in February 2005 and thus was representing both parties at the same time. Rather, Kraus argues in the memorandum, there was no such formal retainer, just the signing of a cost reiumbursement agreement, which actually occurred in February 2004.

Rather, Paget worked for Forest City Ratner through September 2005, then went to work for the state agency the next month--but never for both parties simultaneously. The issue, though, is broader: whether there is an apparent conflict of interest as well.

Edmead wrote, "The Court does not question respondents' contention that it is normal procedure for the applicant to pay for ESDC specialists. However, that does not obviate the obligation to avoid any conflict of interest"--a conflict stemming also from the "oft bottom-line, profit-making pursuits of real estate development corporations" and the "valid environmental interests of the ESDC." Since that pattern may be typical for such large development project, the appellate court must decide is whether it's inappropriate.

Thursday, February 16, 2006

Collaborative, arm's length, or just cheerleading? ESDC's Gargano embraces Ratner plan

One URL for the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), the state's chief economic development agency, is nylovesbiz.com, and the homepage logo features a heart. That suggests that the relationship between the agency, known formally as the New York State Urban Development Corporation, and the businesses it works with is hardly adversarial and may not merely be collaborative--a description offered by an agency lawyer during the court hearing 2/14/06--but positively embracing.

One URL for the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), the state's chief economic development agency, is nylovesbiz.com, and the homepage logo features a heart. That suggests that the relationship between the agency, known formally as the New York State Urban Development Corporation, and the businesses it works with is hardly adversarial and may not merely be collaborative--a description offered by an agency lawyer during the court hearing 2/14/06--but positively embracing.But that rosy image is belied by Justice Carol Edmead's ruling that the lawyer advising ESDC on the proposed demolitions within the Atlantic Yards footprint should be disqualified because he recently worked for developer Forest City Ratner. She called it "a severe, crippling appearance of impropriety," and said that the relationship could not always be collaborative, because the agency and the developer differed at one point on whether the demolitions required agency approval.

Can the agency be expected to do a fair job in both promoting economic development and evaluating the environmental impact of the proposed Atlantic Yards development? ESDC Chairman Charles Gargano gives little cause for confidence. He recently said he knew nothing of any conflict of interest posed by the agency's lawyer, didn't know the agency rents space in a mall owned by Ratner, and endorsed the Atlantic Yards project without reservation, even before the environmental impact statement has been issued.

Can the agency be expected to do a fair job in both promoting economic development and evaluating the environmental impact of the proposed Atlantic Yards development? ESDC Chairman Charles Gargano gives little cause for confidence. He recently said he knew nothing of any conflict of interest posed by the agency's lawyer, didn't know the agency rents space in a mall owned by Ratner, and endorsed the Atlantic Yards project without reservation, even before the environmental impact statement has been issued. Other statements made on the Brian Lehrer Show, cited below, show Gargano unaware that the Atlantic Yards plan began via a developer rather than an open process, overestimating the number of public hearings associated with the review of the Atlantic Yards plan, and claiming--even though his agency's goal is job creation and economic growth--that the reason to support the project is because it would create housing.

Republican fundraiser

Though he had a successful business career, Gargano is better known for his job as a prodigious fundraiser for Republican candidates like President Ronald Reagan, Sen. Alfonse D'Amato, and Gov. George Pataki, who appointed him to his current post. Under the administration of President George H.W. Bush, he was named ambassador to Trinidad & Tobago; he sought the ambassadorship to Italy under the current president, going so far as to submit a letter from Manhattan D.A. Robert Morgenthau clearing him of any wrongdoing in charges of politically-motivated grantsmanship, according to a 3/17/01 article in the New York Times.

An 11/7/99 review by the Daily News showed that 40 of 201 companies that received ESDC loans or grants had given political contributions to Gov. Pataki or other Republican causes. In a 9/26/96 article in Newsday, state Sen. Franz Leichter, a Democrat from Manhattan, called the ESDC a "political slush fund" for Pataki, citing 11 procurement contracts to firms politically linked to Republicans. (Forest City Ratner head Bruce Ratner is a Democrat, but companies he controlled have historically made contributions to various politicians, including $7,500 to since 2000 to state groups affiliated with Governor Pataki, according to a 12/10/03 article in the New York Sun.)

On the radio

On 11/15/05, Gargano appeared on the Brian Lehrer show on WNYC, and was mostly asked about the Atlantic Yards project. Lehrer began by reading an article about a fundraising walk held two days earlier by opponents of the project, citing objections to the density of the plan, the lack of democracy, and to use of eminent domain. He then cited a commentary posted that day by Tom Angotti, a professor of urban studies at Hunter College, that said "the planning for Atlantic Yards is all backwards." Lehrer asked Gargano, "Is this a through-the-looking-glass version of how development should work? (Photo from Brian Lehrer show.)

CG: If you understand development and how it does work, we have a process in government, state government and I’m sure other government bodies have the same, whereby we put out first of all, on any area we’re trying to develop, we put out what we call an RF-- I, request for-- EI, expressions of interest. The reason why we do that is we want to pick the brains of the private sector, and see what kind of ideas they have, and after all, they’re the ones with the resources who are going to build these projects, so we want their ideas. We put out this RFEI, that’s the initial—that’s the first part of the process, and it has worked very well for many, many decades. So it’s not necessarily so that the governments put out a plan of how they want to see something done. An example of that is 42nd Street. Now 42nd Street--the finished product is a very good project, however, that plan, over more than a dozen years, was changed three or four times, until the government came up with a plan that was acceptable to all. So I believe bringing in the private sector, and their ideas, with their engineers and architects, and their resources, is the proper way of going about it.

There was no such RFEI issued for the Atlantic Yards project, though there have been for other projects. As Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz said in affidavit, he urged Bruce Ratner to buy the Nets basketball team, and Ratner concluded that a standalone arena made little economic sense.

The agency had a previous relationship with Ratner, on several projects. For example, as the Village Voice reported in a 6/17/02 article headlined Paper of Wreckage, Gargano met with Ratner in 2000 to discuss the state agency's role in condemning properties on Eighth Avenue in Manhattan for the Times Tower that Forest City Ratner would build in partnership with the New York Times Company.

Avoiding democracy, or just red tape?

Lehrer continued to quote Angotti's essay, pointing out that, because the ESDC is in charge, Forest City Ratner can avoid the city's Uniform Land Use Review Process (ULURP), which would require votes by the local community board, borough president, city planning commission, and city council. Lehrer asked, "So, are you helping Forest City Ratner do an end run around the usual land use democracy?

CG: That’s one way of categorizing it, but we don’t believe that’s the case at all. More than 40 years ago, the Urban Development Corporation [the ESDC’s predecessor name] was created with the powers of getting projects done. That doesn’t mean that we abuse any kind of process or circumvent any process. But what we’re trying to do is get projects built that are in dire need of being developed, such as 42nd Street as I mentioned before, and there’s a whole host of projects. And it’s not a question of circumventing or trying to avoid a process. It’s a way of going about it, with the scoping process that we have, and then environmental impact review. So we go through a lot of process. What we try to eliminate is a lot of red tape that doesn’t necessarily make for a better project

The difference between process and red tape is unclear, but unmentioned was how, by going through the ESDC, the project can override city zoning and be built at a higher density than otherwise allowed.

Lehrer followed up by asking, "Why shouldn’t a big project like this that affects several city neighborhoods go through the ULURP land review process.... Why isn’t that just better democracy?"

CG: Well, you’re going through many, many layers of government, and we don’t think it really is always necessary. As I said before, we do go through a process here, we do go through a scoping process, and we have public hearings to allow the public to comment while we’re going through the scoping process. And then when we develop a draft EIS, we have public hearings once again. In the meanwhile, we have a lot of public hearings, with the community and other members, interested parties. So, it’s a lengthy process in itself, but that doesn’t mean we have to go through many layers of government when sometimes it’s not necessary.

Public hearings? There was only one public hearing so far, on 10/18/05, after the draft scope of analysis was issued, and there may be only one more, after the Draft Environmental Impact Statement is released, likely in the next few months. There are no public hearings "in the meanwhile."

Opponents NIMBYs?

Lehrer pointed out that project opponents were unhappy that there was no public hearing until the one held in the previous month. Gargano responded by raising the spurious NIMBY claim.

CG: Well, one of the things I think we have all learned in our lifetime is the fact that when we are in a particular area, we want nothing else to happen in that area, we don’t want any future development, we don’t want any cleanup, even blighted areas. Look, I received a lot of criticism when we started working on 42nds Street, and we had all these peep shows, sex shops, prostitution, drug sales. And there were objections there, that we were getting a lot of these-- cleaning up a blighted area and getting a lot of these undesirable establishments moved from there. So everyone has their own opinion and that’s fine--

Lehrer interjected, "So it sounds like what you’re saying is the way to keep things moving that the direction that the leaders of the state want is to lock out public input?" Gargano repeated his "process" mantra.

CG: That’s not so. We do have enough public process in everything we do. As I said before, we have a number of public hearings and we do have a process where the public is involved. I don’t think it’s trying to exclude the public. I think what we have to do, when there is a need to accomplish something where it's for the public good, we have to find a way of doing it, and not getting blocked in red tape for long periods of time.

Competing plans

Lehrer read another section from this article, citing the community-developed UNITY plan for the Vanderbilt Yard, as well as the plan for the railyards submitted by the Extell Development Co. that was rejected by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Lehrer asked if it was "right or fair for the MTA to reject the alternative proposals without a public hearing"? Gargano said it wasn't his business.

CG: Well, first of all, the MTA owns the property, you’d have to speak to the MTA on what the process is. But I know that the MTA does own that property, and they have their own processes they have to go through, when they sell their property. So I’m not going to question them, but obviously that question has to go to the MTA.

Lehrer asked, "Do you have your own opinion that the Ratner plan is better on the merits than the Extell plan?"

CG: What I do know is we have a lot more detail on the Ratner plan. We know--again, this is a question of what the MTA has decided, who to sell the property to, we’re not a part of that, Empire State Development. I can tell you what I do know. The Ratner plan is a very detailed extensive plan to clean up the blighted area within that area, finally develop railyards. Isn’t it interesting that these railyards have sat for decades and decades and decades, and no one has done a thing about them, just accepted them in their community, throughout Brooklyn. I remember these yards, I grew up in Park Slope, Brooklyn. These railyards have been sitting there for 40 or 50 years, or longer, obviously, that I remember. The reality is, when someone comes in to develop, all of a sudden everybody is up in arms about how valuable they are. We just had that on the West Side of Manhattan, with the Jets. Now all of a sudden, now that the Jets have decided to stay in New Jersey, which was a big loss in my opinion to us here in New York, now all of a sudden, where’s the interest for those railyards at this point? Very little.

But wasn't it ESDC's job to send out an RFP to develop the railyards, or to work with the MTA to do so? And Gargano failed to acknowledge that the MTA accepted a bid for less than half the appraisal, and for $50 million less than that bid by rival developer Extell.

Nor has the ESDC apparently made any effort to conduct an independent review of the fiscal impact of the Atlantic Yards project, instead relying, in a 3/4/05 press release, on a study conducted by developer Forest City Ratner's paid consultant. Does the ESDC accept fiscal impact studies in the same way it accepts an engineering report regarding emergency demolitions?

Atlantic Yards a "wonderful plan"

Lehrer pointed out that the main opposition group, Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, has pointed out that they don't oppose development, just excessive development. "Why do you think there’s no interest for 40 or 50 years, and then, all of a sudden, there are competing ones?" he asked.

CG: Well, I think what happens, it brings interest to a particular site. As the Jets brought interest to the site on the West Side railyards, similarly here, Forest City Ratner, who has been doing a tremendous amount of good development work, in Brooklyn, downtown Brooklyn, MetroTech and others. They came up with a wonderful plan here, for not only bringing back the Nets, that’s also a plus, but the main reason here is the housing that’s going to be developed, and it’s going to be affordable housing, and it’s going to be set aside for minority workers to work on the particular project, the largest percentages I have ever seen in construction. So therefore it includes the entire community when it’s being developed. It includes the entire community, who want to still live in that area. I don’t know what the other plans are and again, based upon the decision by the MTA, that’s their decision, not ours.

Does MetroTech constitute good development work? Well, it has kept back-office jobs from moving to New Jersey, but only thanks to some significant subsidies, producing a decidedly mixed record, as WNYC has reported

The agency's goal is economic development, not housing, and Atlantic Yards is mostly a project to build luxury housing. Only 2,250 of 7,300 units would be affordable. As for including "the entire community," Gargano apparently hasn't noticed criticism of the Community Benefits Agreement.

Gargano said 2/14/05, commenting on an unrelated issue, "As New Yorkers know, the benefits, programs and services that we provide companies are in return for them creating and retaining jobs in New York State." Note that the number of permanent office jobs at the Atlantic Yards project, once estimated at 10,000, would be no more than 2,500.

Too dense? Not to Gargano

Lehrer asked if he was concerned by the project's density. "A lot of people who even support the idea of this development by Ratner, including the Nets arena, were kind of taken aback when they saw the blueprint," he said.

CG: Well, there’s going to be a lot of open space as well. You can build in many ways, Brian. You can spread it out with lower buildings, or you can concentrate taller buildings and have a lot of open space. The developer proposes to include approximately seven acres of public open space within the project site, with all kinds of amenities. So you have to take the square footage over the entire area. Plus the developing has become more popular, so that we leave open space.

While that last sentence makes no sense, Gargano was repeating Forest City Ratner's claims regarding open space. However, the amount of open space would be far less than recommended by the city, given the population.

Lehrer, citing the one public hearing, asked if there would be more. Gargano repeated his favorite word: process.

CG: Oh, absolutely. There’s a lot more that has to be done. First of all, October 18, we started hearings, during the scoping process. That ended October 28, and now we’re beginning the Draft Environmental Impact Statement, and that’ll take a long period of time. From that, there will be more comment periods, and we’ll have to evaluate those comments before we go into the Final Environmental Impact Statement. So there’s a lot of process yet to go.

Personal qualms?

Lehrer tried to get Gargano to acknowledge any "environmental questions or concerns, any spot that you’re looking at and saying, ‘Well, I’m not sure of this aspect, they’re really going to have to satisfy me on this’?"

CG: I think what we have to do is make sure that we have the proper infrastructure that is required for a development of this type, and we will make sure of that, and that’s part of the environmental impact statement, it takes traffic studies, air quality, and so forth, so--

Lehrer interjected, repeating his question, asking for a personal view, and Gargano repeated himself.

CG: As I said, the infrastructure has to be built in accordance to the needs of this particular development.

Lehrer gave up and turned to questions of Ground Zero.

A few weeks later, Gargano, apparently disregarding process, offered his personal view to the New York Observer: "There is no need to scale down the project."

Wednesday, February 15, 2006

From the case file: $4 million a month (FCR's costs), Roger Green freelances, and the $6 billion deception

For every month Forest City Ratner waits to commence construction on the Atlantic Yards project, it costs the company $4 million. State Assemblyman Roger Green has a novel theory for why the developer traded office space for housing in the Atlantic Yards plan. And 15 public officials, apparently unfazed by parroting the developer's paid consultant, have predicted that the project would bring $6 billion in new tax revenues to the city and state.

Those tidbits and more emerged from the legal papers filed in the case challenging Forest City Ratner's plans to demolish five properties and asserting that a lawyer for the Empire State Development Corporation has a conflict of interest because he previously represented the developer. Yesterday the judge refused to block the demolitions but ordered the attorney removed from the project.

FCR's bottom line

FCR VP Jim Stuckey, in his affidavit, argued against delaying the project, because it would cost the developer $4 million a month. He stated:

FCR VP Jim Stuckey, in his affidavit, argued against delaying the project, because it would cost the developer $4 million a month. He stated:

At this time, it costs FCRC about $2,500,000 per month to carry the real property that it has acquired for the Project and the overhead that is in place to work on the Project - a figure that does not include FCRC's legal fees and also does not include the operating losses that the Nets basketball team, which has been owned by an FCRC affiliate since early 2004, and continues to incur while it is based at its current venue in New Jersey. In addition, delay on a project such as this one probably would subject FCRC to escalation in its eventual construction costs of nearly $1,400,000 per month. Therefore, if a preliminary injunction were to stop the Project temporarily for even one month, the damages to which FCRC would be subjected would exceed $4,000,000 per month.

(Photo from Forest City Ratner web site.)

The model CBA

Why would a brake hurt the public? Stuckey cited jobs, housing, and the Community Benefits Agreement (CBA):

The Community Benefits Agreement is the first such agreement ever entered into by a development in a major development project in New York City. We believe that the Community Benefits Agreement may set the standard for all future major development projects in the City, and FCRC is the first developer to have - and the Project is the first development project- to have undertaken such far-reaching and extensive commitments to the community.

Set the standard? Remember, activists in West Harlem say they're avoiding the Brooklyn model.

Alternatively, it might be argued that the CBA was also promoted to garner political support for a project that would cost the public well over $1 billion.

Economic claims

In his affidavit, Stuckey asserted that the project would be an economic boon: