Friday, February 03, 2006

On a "backwards" design process, "blocking the clock," and a zoning bypass

It's already been said that the planning process for Forest City Ratner's Atlantic Yards project is backwards, but that was by an urban affairs professor. Yesterday, at the Brooklyn Borough Board Atlantic Yards Committee's meeting, the observation came from an insider: Jerry Armer, chair of Community Board 6 and director of services for the Business Improvement District at MetroTech, a Forest City Ratner development.

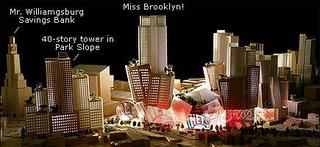

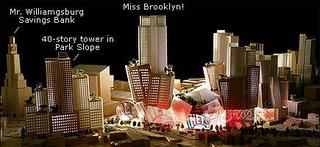

The session addressed issues of urban design, visual resources & neighborhood character. Armer's comment came during a discussion of the urban design guidelines for the project, which have not yet been issued, even though the project was announced on 12/10/03. The Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), the state agency supervising the project, is expected to issue a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) in the next few months. Sometime after that the city, state, and developer, according to the Memorandum of Understanding, should agree on urban design guidelines for the project. (Note that Frank Gehry's 7/5/05 design, above, is expected to be modified.)

The session addressed issues of urban design, visual resources & neighborhood character. Armer's comment came during a discussion of the urban design guidelines for the project, which have not yet been issued, even though the project was announced on 12/10/03. The Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), the state agency supervising the project, is expected to issue a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) in the next few months. Sometime after that the city, state, and developer, according to the Memorandum of Understanding, should agree on urban design guidelines for the project. (Note that Frank Gehry's 7/5/05 design, above, is expected to be modified.)

The guidelines, according to the MOU (p. 2), include such things as "building massing and heights, streetwall location and heights, building articulation, distance between buildings" and "signage, streetscape improvements, public open space use and design guidelines," among others.

When the guidelines are established, will the city consult with local elected officials, City Council Member Letitia James asked Winston Von Engel, of the Department of City Planning.

Von Engel hedged. "That will be up to the head of our agency, and her boss," he said.

Armer brought up the issue a bit later "The EIS is supposed to look at the action if it introduces development with a different basic form or scale. From the models we've seen, the drawings we've seen, not only the arena but the residential buildings--they are very different from what the surrounding area is," he said. "And yet, without knowing exactly what shape they're going to have, we're doing an EIS, with design guidelines to follow. It seems to me it's backwards. The design guidelines should be established so the EIS could evaluate what's really going to be there."

He continued: "I think it's being done backwards, and because of that, how much input will the community boards and elected officials have?"

Von Engel responded by saying that an EIS responds to a proposal, and analyzes the worst case scenario, giving planners options. "What's approved in the end doesn't have to meet that [in the EIS]," he said. "It can be less. It cannot be more."

He said it was his understanding that the General Project Plan--the outline of the project--and the Draft EIS would be issued at the same time.

Views of the bank?

How should we think about the iconic 1929 Williamsburgh Savings Bank, which itself is in transition, from a dental-centric office building to upscale condos? Panelist Michael Kwartler, an architect and planner, pointed out that there may be a loss, of the building becomes less visible, but if the new buildings "are as compelling as they may be, they may supplant" the bank building for orientation.

How should we think about the iconic 1929 Williamsburgh Savings Bank, which itself is in transition, from a dental-centric office building to upscale condos? Panelist Michael Kwartler, an architect and planner, pointed out that there may be a loss, of the building becomes less visible, but if the new buildings "are as compelling as they may be, they may supplant" the bank building for orientation.

James said Brooklynites like herself had long used the building tower for visual orientation and to tell time. "To coin a phrase, 'Don't block the clock,'" she said.

Could mitigation strategies recommended in the EIS include height limits on buildings close to the bank tower, asked Robert Matthews, chair of Community Board 8.

"Sure," said Von Engel, "if the decisionmakers believe that preserving the view of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank is so important... that's part of the approval." He reminded attendees that the EIS is not a decisionmaking document, just a description of potential impacts.

Who are the decisionmakers?

The Borough Board hearings are informational only. James said after the meeting that "the question is whether or not the Borough President is going to address a lot of the issues that have been raised around this table." Borough President Marty Markowitz can influence Mayor Mike Bloomberg and the city agencies that have input on the project.

Crucial to approval of state subsidies are the members of the State Assembly who represent affected areas, notably Assemblyman Roger Green, a supporter of the project, and Assemblywoman Joan Millman, a critic. Both will seek to influence Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, who controls one of the three votes on the Public Authorities Control Board, the agency that shot down the West Side Stadium.

Overriding zoning

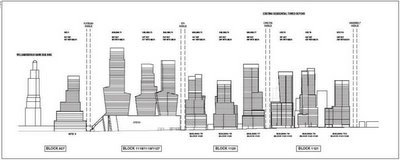

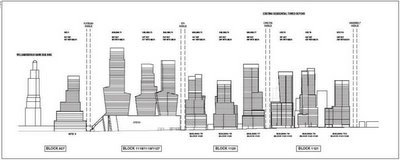

Millman yesterday pointed out that the tallest of 16 towers is slated to be 60 stories. "If this goes through," she asked, "will it set a precedent for other developers" to build similarly in adjoining neighborhoods?

Millman yesterday pointed out that the tallest of 16 towers is slated to be 60 stories. "If this goes through," she asked, "will it set a precedent for other developers" to build similarly in adjoining neighborhoods?

Von Engel answered that, in the adjacent low-rise residential neighborhoods, "we've either rezoned with height limitations ore are considering [similar] actions. Those areas are relatively safe." In Downtown Brooklyn, there are height limits on the east side of Flatbush Avenue, but "within the Central Business District, there is no height limit. What controls height is density. At some point you run out of density."

Architect Mark Ginsburg added, "There are very few sites that large. It's going to be hard to create another site that big to justify the rezoning or a change like this."

Left unstressed was that the Atlantic Yards project would bypass city zoning, which could include either height or density limits to limit the size of the development.

James asked what role the City Planning Department would have.

Von Engel replied, "We are an agency that listens to the mayor, and supports the mayor, who has expressed his support for the project. There is a process by which the state has to request from the city permission to override the zoning and then also to present this project to the city and ask for the city's concurrence."

Demapping streets

Irene Janner of Community Board 2 pointed out that the current plan would include superblocks that take away the street grid, and how it would affect pedestrian circulation.

Ginsburg noted that the space around the residential buildings is considered public open space for pedestrians, even if a street is demapped. "That's something we'd hope in the final document is much more clearly identified," he said.

Kwartler observed that land between certain Mitchell-Lama projects is considered public, "but basically it's private property, not a public street." He added, "One alternative [for Atlantic Yards] might be remapping thes treets back through."

Others were more positive. Von Engel pointed out that the project "might actually bring the communities closer together." Greg Atkins, chief of staff for Markowitz, asked whether the EIS would analyze the effect of "negative views," like the view of the railyard from the Sixth Avenue bridge. "Are views not as beautiful analyzed in the EIS?"

Ginsburg said yes, that the state guidelines say that creating new visual resources "can be a mitigation" of a project's effects.

Is there a city policy regarding demapping streets, asked Irene Van Slyke, representing State Senator Velmanette Montgomery.

"I don't think there's one policy for demapping or mapping streets," Von Engel replied. "In Downtown Brooklyn, we demapped streets to create more rational building sites, more rational blocks, because the leftover remnants were not lending themselves to be building on. But in other cases, we've mapped streets back and we appreciate the life that streets bring. There is no one set policy."

Van Slyke warned that demapped streets can lead to privatization.

Von Engel referred to the MOU, which spells out publicly-accessible open space and noted that, in public-private plazas sanctioned by the city, "We have plaques to announce, 'This is publicly-accessible.'"

James reflected that, typically, demapping streets would go through the city's ULURP (Uniform Land Use Review Procedure) but in this case ULURP has been overridden.

Kwartler observed that the EIS process can propose reconfigured plans, but gave listeners less cause to expect that: "There tends to be a loss of an opportunity when the state does this rather than when the city does this."

New glare?

Markowitz pointed out that the arena would bring new large-scale signage with "advertising lighting," and asked how the EIS would analyze it.

Kwartler said the lighting might bring glare, perhaps so bright it would obscure the Williamsburgh Savings Bank. "You can either think of it as a positive or as light pollution," he added, noting that it might be helpful to pedestrians but a traffic hazard for vehicles.

Offering "an overall comment" about the EIS process, he said, "I think what it generally lacks are objective ways that define in advance" the issues to be evaluated.

The session addressed issues of urban design, visual resources & neighborhood character. Armer's comment came during a discussion of the urban design guidelines for the project, which have not yet been issued, even though the project was announced on 12/10/03. The Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), the state agency supervising the project, is expected to issue a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) in the next few months. Sometime after that the city, state, and developer, according to the Memorandum of Understanding, should agree on urban design guidelines for the project. (Note that Frank Gehry's 7/5/05 design, above, is expected to be modified.)

The session addressed issues of urban design, visual resources & neighborhood character. Armer's comment came during a discussion of the urban design guidelines for the project, which have not yet been issued, even though the project was announced on 12/10/03. The Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), the state agency supervising the project, is expected to issue a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) in the next few months. Sometime after that the city, state, and developer, according to the Memorandum of Understanding, should agree on urban design guidelines for the project. (Note that Frank Gehry's 7/5/05 design, above, is expected to be modified.)The guidelines, according to the MOU (p. 2), include such things as "building massing and heights, streetwall location and heights, building articulation, distance between buildings" and "signage, streetscape improvements, public open space use and design guidelines," among others.

When the guidelines are established, will the city consult with local elected officials, City Council Member Letitia James asked Winston Von Engel, of the Department of City Planning.

Von Engel hedged. "That will be up to the head of our agency, and her boss," he said.

Armer brought up the issue a bit later "The EIS is supposed to look at the action if it introduces development with a different basic form or scale. From the models we've seen, the drawings we've seen, not only the arena but the residential buildings--they are very different from what the surrounding area is," he said. "And yet, without knowing exactly what shape they're going to have, we're doing an EIS, with design guidelines to follow. It seems to me it's backwards. The design guidelines should be established so the EIS could evaluate what's really going to be there."

He continued: "I think it's being done backwards, and because of that, how much input will the community boards and elected officials have?"

Von Engel responded by saying that an EIS responds to a proposal, and analyzes the worst case scenario, giving planners options. "What's approved in the end doesn't have to meet that [in the EIS]," he said. "It can be less. It cannot be more."

He said it was his understanding that the General Project Plan--the outline of the project--and the Draft EIS would be issued at the same time.

Views of the bank?

How should we think about the iconic 1929 Williamsburgh Savings Bank, which itself is in transition, from a dental-centric office building to upscale condos? Panelist Michael Kwartler, an architect and planner, pointed out that there may be a loss, of the building becomes less visible, but if the new buildings "are as compelling as they may be, they may supplant" the bank building for orientation.

How should we think about the iconic 1929 Williamsburgh Savings Bank, which itself is in transition, from a dental-centric office building to upscale condos? Panelist Michael Kwartler, an architect and planner, pointed out that there may be a loss, of the building becomes less visible, but if the new buildings "are as compelling as they may be, they may supplant" the bank building for orientation.James said Brooklynites like herself had long used the building tower for visual orientation and to tell time. "To coin a phrase, 'Don't block the clock,'" she said.

Could mitigation strategies recommended in the EIS include height limits on buildings close to the bank tower, asked Robert Matthews, chair of Community Board 8.

"Sure," said Von Engel, "if the decisionmakers believe that preserving the view of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank is so important... that's part of the approval." He reminded attendees that the EIS is not a decisionmaking document, just a description of potential impacts.

Who are the decisionmakers?

The Borough Board hearings are informational only. James said after the meeting that "the question is whether or not the Borough President is going to address a lot of the issues that have been raised around this table." Borough President Marty Markowitz can influence Mayor Mike Bloomberg and the city agencies that have input on the project.

Crucial to approval of state subsidies are the members of the State Assembly who represent affected areas, notably Assemblyman Roger Green, a supporter of the project, and Assemblywoman Joan Millman, a critic. Both will seek to influence Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, who controls one of the three votes on the Public Authorities Control Board, the agency that shot down the West Side Stadium.

Overriding zoning

Millman yesterday pointed out that the tallest of 16 towers is slated to be 60 stories. "If this goes through," she asked, "will it set a precedent for other developers" to build similarly in adjoining neighborhoods?

Millman yesterday pointed out that the tallest of 16 towers is slated to be 60 stories. "If this goes through," she asked, "will it set a precedent for other developers" to build similarly in adjoining neighborhoods?Von Engel answered that, in the adjacent low-rise residential neighborhoods, "we've either rezoned with height limitations ore are considering [similar] actions. Those areas are relatively safe." In Downtown Brooklyn, there are height limits on the east side of Flatbush Avenue, but "within the Central Business District, there is no height limit. What controls height is density. At some point you run out of density."

Architect Mark Ginsburg added, "There are very few sites that large. It's going to be hard to create another site that big to justify the rezoning or a change like this."

Left unstressed was that the Atlantic Yards project would bypass city zoning, which could include either height or density limits to limit the size of the development.

James asked what role the City Planning Department would have.

Von Engel replied, "We are an agency that listens to the mayor, and supports the mayor, who has expressed his support for the project. There is a process by which the state has to request from the city permission to override the zoning and then also to present this project to the city and ask for the city's concurrence."

Demapping streets

Irene Janner of Community Board 2 pointed out that the current plan would include superblocks that take away the street grid, and how it would affect pedestrian circulation.

Ginsburg noted that the space around the residential buildings is considered public open space for pedestrians, even if a street is demapped. "That's something we'd hope in the final document is much more clearly identified," he said.

Kwartler observed that land between certain Mitchell-Lama projects is considered public, "but basically it's private property, not a public street." He added, "One alternative [for Atlantic Yards] might be remapping thes treets back through."

Others were more positive. Von Engel pointed out that the project "might actually bring the communities closer together." Greg Atkins, chief of staff for Markowitz, asked whether the EIS would analyze the effect of "negative views," like the view of the railyard from the Sixth Avenue bridge. "Are views not as beautiful analyzed in the EIS?"

Ginsburg said yes, that the state guidelines say that creating new visual resources "can be a mitigation" of a project's effects.

Is there a city policy regarding demapping streets, asked Irene Van Slyke, representing State Senator Velmanette Montgomery.

"I don't think there's one policy for demapping or mapping streets," Von Engel replied. "In Downtown Brooklyn, we demapped streets to create more rational building sites, more rational blocks, because the leftover remnants were not lending themselves to be building on. But in other cases, we've mapped streets back and we appreciate the life that streets bring. There is no one set policy."

Van Slyke warned that demapped streets can lead to privatization.

Von Engel referred to the MOU, which spells out publicly-accessible open space and noted that, in public-private plazas sanctioned by the city, "We have plaques to announce, 'This is publicly-accessible.'"

James reflected that, typically, demapping streets would go through the city's ULURP (Uniform Land Use Review Procedure) but in this case ULURP has been overridden.

Kwartler observed that the EIS process can propose reconfigured plans, but gave listeners less cause to expect that: "There tends to be a loss of an opportunity when the state does this rather than when the city does this."

New glare?

Markowitz pointed out that the arena would bring new large-scale signage with "advertising lighting," and asked how the EIS would analyze it.

Kwartler said the lighting might bring glare, perhaps so bright it would obscure the Williamsburgh Savings Bank. "You can either think of it as a positive or as light pollution," he added, noting that it might be helpful to pedestrians but a traffic hazard for vehicles.

Offering "an overall comment" about the EIS process, he said, "I think what it generally lacks are objective ways that define in advance" the issues to be evaluated.