Friday, February 24, 2006

Zoning stasis (for 45 years), the local downzoning push, and the Atlantic Yards bypass

Development in New York is usually shaped by zoning--though the state would override city zoning for the Atlantic Yards project--and the building boom around the city has caused local officials and neighborhood activists to wake up. "For the most part, the zoning we have in New York is from 1961," Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society, recently told the real estate monthly The Real Deal. "That rezoning was based on the expectation that the city's population would double over the next 40 years, which hasn't come close to happening."

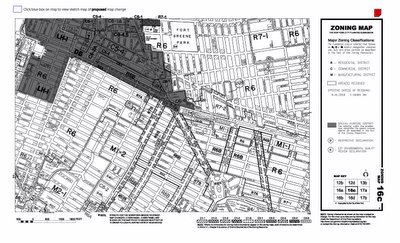

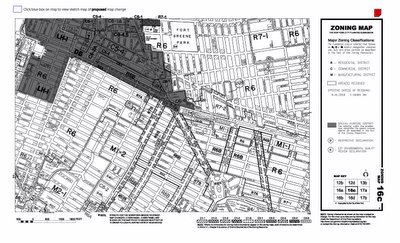

For example, parts of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, have R6 zoning. As the Fort Greene Association (FGA) has pointed out, a typical R6 development is between three and 12 stories. While the zoning code supports "construction of tall, slender buildings surrounded by large, open spaces," the FGA would prefer more contexual buildings that produce similar square footage but cover larger portions of the lots, under R6B zoning. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) in R6 districts ranges from 0.78 to 2.43, while R6B would have an FAR of 2.0. (Remember, the FAR for the Atlantic Yards project would be much larger, from 9.5 to 12, depending on how it's calculated, according to architect Jonathan Cohn.)

For example, parts of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, have R6 zoning. As the Fort Greene Association (FGA) has pointed out, a typical R6 development is between three and 12 stories. While the zoning code supports "construction of tall, slender buildings surrounded by large, open spaces," the FGA would prefer more contexual buildings that produce similar square footage but cover larger portions of the lots, under R6B zoning. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) in R6 districts ranges from 0.78 to 2.43, while R6B would have an FAR of 2.0. (Remember, the FAR for the Atlantic Yards project would be much larger, from 9.5 to 12, depending on how it's calculated, according to architect Jonathan Cohn.)

The response: downzoning

As noted by The Real Deal, in the article headlined Looking for an upside to downzoning, the local backlash has led to new zoning restrictions on building heights and density in neighborhoods such as Bensonhurst, South Park Slope, and Bay Ridge. (This is separate from the rezoning to spur development in Williamsburg/Greenpoint and elsewhere.) "The key phrase invoked with these rules is 'preservation of the existing character of the neighborhood,'" the article stated.

At a panel 2/21/06 organized by the Historic Districts Council, titled "Neighborhood Preservation in Brooklyn: Preserving the Past, Planning the Future," several people pointed to the rapid change and the belated response. "Brooklyn has been complacent," observed architectural historian Andrew Dolkart, who noted that the last sizable historic district in Brooklyn was established in 1982. "If nothing else good comes out of Atlantic Yards," he said, "it will be that people have woken up to the fact" that they must much more closely consider the built environment.

Dolkart pointed to efforts to add blocks to the Fort Greene and Clinton Hill historic districts, and the need to preserve Wallabout, the area between Myrtle Avenue and the Brooklyn Navy Yard. (Note that the panel specifically aimed not to address the Atlantic Yards project.)

It's political

Asked what role politics should play in community preservation, Aaron Brashear of the Concerned Citizens of Greenwood Heights commented, "In our case, very heavily." He said his group lobbied the local community board, elected officials, and the city planning office: "We were fortunate there weren't too many developers in our neighborhood with their hands in political pockets."

"We live in a democracy," said Winston Von Engel, of the Department of City Planning. "You can use political pressure and reason. Zoning changes usually come from the grassroots." A question for those watching the Atlantic Yards project remains: how much leverage does the public have in a state process that overrides zoning and is supervised by the Empire State Development Corporation?

For example, parts of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, have R6 zoning. As the Fort Greene Association (FGA) has pointed out, a typical R6 development is between three and 12 stories. While the zoning code supports "construction of tall, slender buildings surrounded by large, open spaces," the FGA would prefer more contexual buildings that produce similar square footage but cover larger portions of the lots, under R6B zoning. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) in R6 districts ranges from 0.78 to 2.43, while R6B would have an FAR of 2.0. (Remember, the FAR for the Atlantic Yards project would be much larger, from 9.5 to 12, depending on how it's calculated, according to architect Jonathan Cohn.)

For example, parts of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, have R6 zoning. As the Fort Greene Association (FGA) has pointed out, a typical R6 development is between three and 12 stories. While the zoning code supports "construction of tall, slender buildings surrounded by large, open spaces," the FGA would prefer more contexual buildings that produce similar square footage but cover larger portions of the lots, under R6B zoning. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) in R6 districts ranges from 0.78 to 2.43, while R6B would have an FAR of 2.0. (Remember, the FAR for the Atlantic Yards project would be much larger, from 9.5 to 12, depending on how it's calculated, according to architect Jonathan Cohn.)The response: downzoning

As noted by The Real Deal, in the article headlined Looking for an upside to downzoning, the local backlash has led to new zoning restrictions on building heights and density in neighborhoods such as Bensonhurst, South Park Slope, and Bay Ridge. (This is separate from the rezoning to spur development in Williamsburg/Greenpoint and elsewhere.) "The key phrase invoked with these rules is 'preservation of the existing character of the neighborhood,'" the article stated.

At a panel 2/21/06 organized by the Historic Districts Council, titled "Neighborhood Preservation in Brooklyn: Preserving the Past, Planning the Future," several people pointed to the rapid change and the belated response. "Brooklyn has been complacent," observed architectural historian Andrew Dolkart, who noted that the last sizable historic district in Brooklyn was established in 1982. "If nothing else good comes out of Atlantic Yards," he said, "it will be that people have woken up to the fact" that they must much more closely consider the built environment.

Dolkart pointed to efforts to add blocks to the Fort Greene and Clinton Hill historic districts, and the need to preserve Wallabout, the area between Myrtle Avenue and the Brooklyn Navy Yard. (Note that the panel specifically aimed not to address the Atlantic Yards project.)

It's political

Asked what role politics should play in community preservation, Aaron Brashear of the Concerned Citizens of Greenwood Heights commented, "In our case, very heavily." He said his group lobbied the local community board, elected officials, and the city planning office: "We were fortunate there weren't too many developers in our neighborhood with their hands in political pockets."

"We live in a democracy," said Winston Von Engel, of the Department of City Planning. "You can use political pressure and reason. Zoning changes usually come from the grassroots." A question for those watching the Atlantic Yards project remains: how much leverage does the public have in a state process that overrides zoning and is supervised by the Empire State Development Corporation?