Wednesday, March 01, 2006

Introducing the Atlantic Yards Report

From today onward, my reportage, analysis, and commentary on the Atlantic Yards project will appear at the Atlantic Yards Report.

This blog, originally dubbed TimesRatnerReport, was conceived to accompany the 9/1/05 publication of my report The New York Times & Forest City Ratner's Atlantic Yards: High Rises & Low Standards. I thought a blog could help track and comment on the response to my report.

The report has not yet spurred the Public Editor of the New York Times to assess the newspaper's coverage of the Atlantic Yards project. However, I do think my criticisms have contributed to a somewhat better performance by the media, including the Times.

Moreover, the report and the research behind it have served as a base for an evolving blog. While I initially emphasized media analysis and commentary, I now include much more original reporting.

Given the broader focus, the name TimesRatnerReport doesn't fit as well. The blog under that URL will remain intact, and I will link back from the Atlantic Yards Report to old blog entries when necessary. (Why not simply change the name/URL of the old blog? Many original links would be lost.)

I will continue my analysis of the New York Times's coverage, and of media coverage in general. But I also will continue to take a broader view of the biggest development project in the history of Brooklyn.

This blog, originally dubbed TimesRatnerReport, was conceived to accompany the 9/1/05 publication of my report The New York Times & Forest City Ratner's Atlantic Yards: High Rises & Low Standards. I thought a blog could help track and comment on the response to my report.

The report has not yet spurred the Public Editor of the New York Times to assess the newspaper's coverage of the Atlantic Yards project. However, I do think my criticisms have contributed to a somewhat better performance by the media, including the Times.

Moreover, the report and the research behind it have served as a base for an evolving blog. While I initially emphasized media analysis and commentary, I now include much more original reporting.

Given the broader focus, the name TimesRatnerReport doesn't fit as well. The blog under that URL will remain intact, and I will link back from the Atlantic Yards Report to old blog entries when necessary. (Why not simply change the name/URL of the old blog? Many original links would be lost.)

I will continue my analysis of the New York Times's coverage, and of media coverage in general. But I also will continue to take a broader view of the biggest development project in the history of Brooklyn.

Tuesday, February 28, 2006

ESDC: terrorism not part of Environmental Impact Statement

Ok, this isn't new, given that the discussion happened four months ago, but it's news because it hasn't been reported before: The Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), which in perhaps a month will issue a Draft Environmental Impact Statement regarding the Atlantic Yards plan, will not go beyond its legal mandate to consider terrorism as a separate issue.

On 10/24/05, even before the comment period on the Draft Scope of Analysis had closed, ESDC officials met with Brooklyn elected officials and others in the first session of Borough Board Atlantic Yards Committee.

I wasn't there and the recently-posted notes are terse, but here it is:

Will terrorism be taken into consideration as part of the EIS?

No. It is not in the scope of the EIS, but ESDC heard this recommendation at the public hearing.

Thus, the ESDC apparently won't heed the requests of the Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods and community boards to consider terrorism, an issue I wrote about before the 10/24/05 notes were posted.

That's not to say that the New York Police Department won't evaluate security issues, as it's been asked to do--though the report hasn't yet been released). But the law governing the EIS--which was written, of course, before the 9/11 attacks raised public consciousness about terrorism--doesn't require the state to do so.

As with the ESDC's close relationship with developers, which is part of its mission, the statute governing the scope of the EIS might deserve another look.

On 10/24/05, even before the comment period on the Draft Scope of Analysis had closed, ESDC officials met with Brooklyn elected officials and others in the first session of Borough Board Atlantic Yards Committee.

I wasn't there and the recently-posted notes are terse, but here it is:

Will terrorism be taken into consideration as part of the EIS?

No. It is not in the scope of the EIS, but ESDC heard this recommendation at the public hearing.

Thus, the ESDC apparently won't heed the requests of the Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods and community boards to consider terrorism, an issue I wrote about before the 10/24/05 notes were posted.

That's not to say that the New York Police Department won't evaluate security issues, as it's been asked to do--though the report hasn't yet been released). But the law governing the EIS--which was written, of course, before the 9/11 attacks raised public consciousness about terrorism--doesn't require the state to do so.

As with the ESDC's close relationship with developers, which is part of its mission, the statute governing the scope of the EIS might deserve another look.

Saturday, February 25, 2006

An alternative to Ratner's CBA? Development groups work toward new principles

Was the Atlantic Yards plan just a few years too soon for economic development groups to get organized? That's one conclusion from Mark Winston Griffith's article Redefining Economic Development in the February Gotham Gazette.

Griffith wrote:

A fledgling coalition of some of the most prominent economic development groups in the city have been meeting over the last year to create a blueprint that offers a comprehensive and alternative vision of what development should look like in the Bloomberg era. “Re-Defining Economic Development” -- or RED NY, as this coalition’s efforts are called -- began as an attempt to make new development projects in the city more accountable. Its participants all have the conviction that New York’s prosperity should be shared more broadly throughout the city.

While the Atlantic Yards plan was announced in December 2003, RED NY's precursors began in the following year:

The roots of Re-Defining New York go back to a series of meetings in 2004 -– the Subsidy Accountability Strategy Session -- that were put together by Jobs with Justice New York, a group that organizes to support the rights of workers and increase their standard of living. At these meetings more than 40 organizations, including the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, Good Jobs New York and the Pratt Center for Community Development, attempted to figure out how to demand more public benefit from projects that received incentives and subsidies from the city and state coffers.

It took more than a year to reconstitute the group:

[A]t a meeting in November of 2005, Jobs with Justice, along with Good Jobs and Pratt, again invited dozens of activists to participate in a series of meetings, this time called Re-Defining Economic Development (RED NY).

Since the November meeting of RED NY, a working group consisting of more than a dozen organizations has emerged to establish a set of principles that could possibly be “endorsed” by a broad range of organizing and advocacy groups in the city. One suggestion is that these principles could then be used to judge the candidates for governor, and encourage them to adopt a progressive platform on economic development. RED NY is also organizing training sessions designed to help people from different economic development disciplines establish common ground and a common understanding of the issues.

Atlantic Yards alternatives?

The principles developed could have had consequences for the Atlantic Yards plan:

But Michelle de la Uz, executive director of the Fifth Avenue Committee, is very clear on the practical uses for a new economic development blueprint. The Fifth Avenue Committee is one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit to stop Bruce Ratner from demolishing six buildings en route to building the Nets stadium and hundreds of commercial and residential units over Atlantic Yards in downtown Brooklyn.

(Note that Atlantic Yards not a place but a project that includes the MTA's Vanderbilt Yards, and it's near downtown.)

While the developer Forest City Ratner and eight community groups, several of them with no track record, negotiated a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA), that has been widely criticized. But it was the city's first CBA, and there were no standards. As Griffiths wrote:

What de la Uz envisions is a set of standards for job creation, environmental impact, buy-in from the surrounding area, etc. that the city or a private developer could be held to whenever they planned to use public resources. In her opinion such a standard would have set a much higher bar for Ratner to clear before he was able to pursue the Nets Arena project. The surrounding neighborhood, in de la Uz’s opinion, would have had “real” community benefit “guarantees” instead of what she considers to be the highly questionable and unenforceable promises for job creation and affordable housing that Ratner was able to negotiate.

Griffith wrote:

A fledgling coalition of some of the most prominent economic development groups in the city have been meeting over the last year to create a blueprint that offers a comprehensive and alternative vision of what development should look like in the Bloomberg era. “Re-Defining Economic Development” -- or RED NY, as this coalition’s efforts are called -- began as an attempt to make new development projects in the city more accountable. Its participants all have the conviction that New York’s prosperity should be shared more broadly throughout the city.

While the Atlantic Yards plan was announced in December 2003, RED NY's precursors began in the following year:

The roots of Re-Defining New York go back to a series of meetings in 2004 -– the Subsidy Accountability Strategy Session -- that were put together by Jobs with Justice New York, a group that organizes to support the rights of workers and increase their standard of living. At these meetings more than 40 organizations, including the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, Good Jobs New York and the Pratt Center for Community Development, attempted to figure out how to demand more public benefit from projects that received incentives and subsidies from the city and state coffers.

It took more than a year to reconstitute the group:

[A]t a meeting in November of 2005, Jobs with Justice, along with Good Jobs and Pratt, again invited dozens of activists to participate in a series of meetings, this time called Re-Defining Economic Development (RED NY).

Since the November meeting of RED NY, a working group consisting of more than a dozen organizations has emerged to establish a set of principles that could possibly be “endorsed” by a broad range of organizing and advocacy groups in the city. One suggestion is that these principles could then be used to judge the candidates for governor, and encourage them to adopt a progressive platform on economic development. RED NY is also organizing training sessions designed to help people from different economic development disciplines establish common ground and a common understanding of the issues.

Atlantic Yards alternatives?

The principles developed could have had consequences for the Atlantic Yards plan:

But Michelle de la Uz, executive director of the Fifth Avenue Committee, is very clear on the practical uses for a new economic development blueprint. The Fifth Avenue Committee is one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit to stop Bruce Ratner from demolishing six buildings en route to building the Nets stadium and hundreds of commercial and residential units over Atlantic Yards in downtown Brooklyn.

(Note that Atlantic Yards not a place but a project that includes the MTA's Vanderbilt Yards, and it's near downtown.)

While the developer Forest City Ratner and eight community groups, several of them with no track record, negotiated a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA), that has been widely criticized. But it was the city's first CBA, and there were no standards. As Griffiths wrote:

What de la Uz envisions is a set of standards for job creation, environmental impact, buy-in from the surrounding area, etc. that the city or a private developer could be held to whenever they planned to use public resources. In her opinion such a standard would have set a much higher bar for Ratner to clear before he was able to pursue the Nets Arena project. The surrounding neighborhood, in de la Uz’s opinion, would have had “real” community benefit “guarantees” instead of what she considers to be the highly questionable and unenforceable promises for job creation and affordable housing that Ratner was able to negotiate.

Friday, February 24, 2006

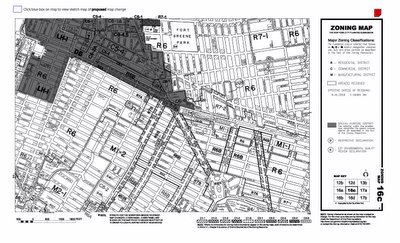

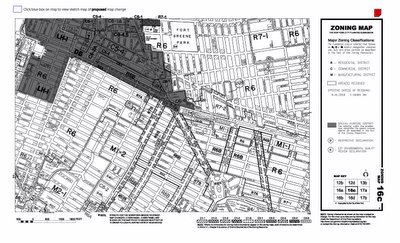

Zoning stasis (for 45 years), the local downzoning push, and the Atlantic Yards bypass

Development in New York is usually shaped by zoning--though the state would override city zoning for the Atlantic Yards project--and the building boom around the city has caused local officials and neighborhood activists to wake up. "For the most part, the zoning we have in New York is from 1961," Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society, recently told the real estate monthly The Real Deal. "That rezoning was based on the expectation that the city's population would double over the next 40 years, which hasn't come close to happening."

For example, parts of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, have R6 zoning. As the Fort Greene Association (FGA) has pointed out, a typical R6 development is between three and 12 stories. While the zoning code supports "construction of tall, slender buildings surrounded by large, open spaces," the FGA would prefer more contexual buildings that produce similar square footage but cover larger portions of the lots, under R6B zoning. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) in R6 districts ranges from 0.78 to 2.43, while R6B would have an FAR of 2.0. (Remember, the FAR for the Atlantic Yards project would be much larger, from 9.5 to 12, depending on how it's calculated, according to architect Jonathan Cohn.)

For example, parts of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, have R6 zoning. As the Fort Greene Association (FGA) has pointed out, a typical R6 development is between three and 12 stories. While the zoning code supports "construction of tall, slender buildings surrounded by large, open spaces," the FGA would prefer more contexual buildings that produce similar square footage but cover larger portions of the lots, under R6B zoning. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) in R6 districts ranges from 0.78 to 2.43, while R6B would have an FAR of 2.0. (Remember, the FAR for the Atlantic Yards project would be much larger, from 9.5 to 12, depending on how it's calculated, according to architect Jonathan Cohn.)

The response: downzoning

As noted by The Real Deal, in the article headlined Looking for an upside to downzoning, the local backlash has led to new zoning restrictions on building heights and density in neighborhoods such as Bensonhurst, South Park Slope, and Bay Ridge. (This is separate from the rezoning to spur development in Williamsburg/Greenpoint and elsewhere.) "The key phrase invoked with these rules is 'preservation of the existing character of the neighborhood,'" the article stated.

At a panel 2/21/06 organized by the Historic Districts Council, titled "Neighborhood Preservation in Brooklyn: Preserving the Past, Planning the Future," several people pointed to the rapid change and the belated response. "Brooklyn has been complacent," observed architectural historian Andrew Dolkart, who noted that the last sizable historic district in Brooklyn was established in 1982. "If nothing else good comes out of Atlantic Yards," he said, "it will be that people have woken up to the fact" that they must much more closely consider the built environment.

Dolkart pointed to efforts to add blocks to the Fort Greene and Clinton Hill historic districts, and the need to preserve Wallabout, the area between Myrtle Avenue and the Brooklyn Navy Yard. (Note that the panel specifically aimed not to address the Atlantic Yards project.)

It's political

Asked what role politics should play in community preservation, Aaron Brashear of the Concerned Citizens of Greenwood Heights commented, "In our case, very heavily." He said his group lobbied the local community board, elected officials, and the city planning office: "We were fortunate there weren't too many developers in our neighborhood with their hands in political pockets."

"We live in a democracy," said Winston Von Engel, of the Department of City Planning. "You can use political pressure and reason. Zoning changes usually come from the grassroots." A question for those watching the Atlantic Yards project remains: how much leverage does the public have in a state process that overrides zoning and is supervised by the Empire State Development Corporation?

For example, parts of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, have R6 zoning. As the Fort Greene Association (FGA) has pointed out, a typical R6 development is between three and 12 stories. While the zoning code supports "construction of tall, slender buildings surrounded by large, open spaces," the FGA would prefer more contexual buildings that produce similar square footage but cover larger portions of the lots, under R6B zoning. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) in R6 districts ranges from 0.78 to 2.43, while R6B would have an FAR of 2.0. (Remember, the FAR for the Atlantic Yards project would be much larger, from 9.5 to 12, depending on how it's calculated, according to architect Jonathan Cohn.)

For example, parts of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, have R6 zoning. As the Fort Greene Association (FGA) has pointed out, a typical R6 development is between three and 12 stories. While the zoning code supports "construction of tall, slender buildings surrounded by large, open spaces," the FGA would prefer more contexual buildings that produce similar square footage but cover larger portions of the lots, under R6B zoning. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) in R6 districts ranges from 0.78 to 2.43, while R6B would have an FAR of 2.0. (Remember, the FAR for the Atlantic Yards project would be much larger, from 9.5 to 12, depending on how it's calculated, according to architect Jonathan Cohn.)The response: downzoning

As noted by The Real Deal, in the article headlined Looking for an upside to downzoning, the local backlash has led to new zoning restrictions on building heights and density in neighborhoods such as Bensonhurst, South Park Slope, and Bay Ridge. (This is separate from the rezoning to spur development in Williamsburg/Greenpoint and elsewhere.) "The key phrase invoked with these rules is 'preservation of the existing character of the neighborhood,'" the article stated.

At a panel 2/21/06 organized by the Historic Districts Council, titled "Neighborhood Preservation in Brooklyn: Preserving the Past, Planning the Future," several people pointed to the rapid change and the belated response. "Brooklyn has been complacent," observed architectural historian Andrew Dolkart, who noted that the last sizable historic district in Brooklyn was established in 1982. "If nothing else good comes out of Atlantic Yards," he said, "it will be that people have woken up to the fact" that they must much more closely consider the built environment.

Dolkart pointed to efforts to add blocks to the Fort Greene and Clinton Hill historic districts, and the need to preserve Wallabout, the area between Myrtle Avenue and the Brooklyn Navy Yard. (Note that the panel specifically aimed not to address the Atlantic Yards project.)

It's political

Asked what role politics should play in community preservation, Aaron Brashear of the Concerned Citizens of Greenwood Heights commented, "In our case, very heavily." He said his group lobbied the local community board, elected officials, and the city planning office: "We were fortunate there weren't too many developers in our neighborhood with their hands in political pockets."

"We live in a democracy," said Winston Von Engel, of the Department of City Planning. "You can use political pressure and reason. Zoning changes usually come from the grassroots." A question for those watching the Atlantic Yards project remains: how much leverage does the public have in a state process that overrides zoning and is supervised by the Empire State Development Corporation?

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

A Times roundup on eminent domain: no mention of Brooklyn or the newspaper's own history

The New York Times offers a front-page article on eminent domain today, headlined States Curbing Right to Seize Private Homes. It's one of those national roundups, covering a lot of bases, with a nod to issues in the tristate area. There's no mention of the Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn or the parent Times Company's own use of eminent domain.

There's a finite amount of space for such an article, so it's a judgment call about what to include. And the New York Times is a national newspaper. Still, its center of gravity is New York City, and there's a strong case that even roundup articles should mention its home city where eminent domain is at issue--such as the Atlantic Yards project. Perhaps this is caused by balkanization of coverage. As noted in Chapter 9 of my report, the national desk's coverage of the Supreme Court's Kelo decision--the ruling that sparked the new state legislation discussed today--neglected the local angle.

[Update: a reader comments that the reporter was writing a roundup of state legislative efforts, not the eminent domain issue in general, so the failure to mention the Brooklyn issue was defensible. Yes, I should've been more precise. Still, the article did mention some the impact of state reforms on some specific projects: a new stadium for the Dallas Cowboys, a Texas highway project, and a case in the Cincinnati suburb of Norwood. The issue in Brooklyn may not be as prominent in New York, relatively speaking, as the other cases mentioned are in their states. Then again, the Times should think of its local readers as well.]

There's also a case that the Times should disclose its own corporate role; it has not done so regularly but did in a 1/26/06 article (from the business/financial desk) headlined Bank to Deny Loans if Land Was Seized: "The New York Times Company used eminent domain to acquire the land for its new headquarters under construction in Midtown." [Addendum: After some discussion, I'll suggest that it is a judgment call, and the case is strongest when the Times is writing about the use of eminent domain in New York--which was not the subject of this article.]

Today's article included these passages:

The issue was one of the first raised when Connecticut lawmakers returned to session early this month. There are bills pending in the Legislature to impose new restrictions on the use of eminent domain by local governments and to assure that displaced businesses and homeowners receive fair compensation.

(The New London project is essentially delayed, even after the Supreme Court go-ahead, because of contractual disputes and an unwillingness to forcibly remove the homeowners who sued to save their properties.)

In the New Jersey Legislature, Senator Nia H. Gill, a Democrat from Montclair who is chairwoman of the Commerce Committee, proposed a bill to outlaw the use of eminent domain to condemn residential property that is not completely run down to make room for a redevelopment project. The bill, which is pending, would require public hearings before any taking of private property to benefit a private project.

In New York, State Senator John A. DeFrancisco, a Republican, has proposed a measure similar to one in other states that would remove the right to exercise condemnation power from unelected bodies like an urban redevelopment authority or an industrial development agency.

There's a finite amount of space for such an article, so it's a judgment call about what to include. And the New York Times is a national newspaper. Still, its center of gravity is New York City, and there's a strong case that even roundup articles should mention its home city where eminent domain is at issue--such as the Atlantic Yards project. Perhaps this is caused by balkanization of coverage. As noted in Chapter 9 of my report, the national desk's coverage of the Supreme Court's Kelo decision--the ruling that sparked the new state legislation discussed today--neglected the local angle.

[Update: a reader comments that the reporter was writing a roundup of state legislative efforts, not the eminent domain issue in general, so the failure to mention the Brooklyn issue was defensible. Yes, I should've been more precise. Still, the article did mention some the impact of state reforms on some specific projects: a new stadium for the Dallas Cowboys, a Texas highway project, and a case in the Cincinnati suburb of Norwood. The issue in Brooklyn may not be as prominent in New York, relatively speaking, as the other cases mentioned are in their states. Then again, the Times should think of its local readers as well.]

There's also a case that the Times should disclose its own corporate role; it has not done so regularly but did in a 1/26/06 article (from the business/financial desk) headlined Bank to Deny Loans if Land Was Seized: "The New York Times Company used eminent domain to acquire the land for its new headquarters under construction in Midtown." [Addendum: After some discussion, I'll suggest that it is a judgment call, and the case is strongest when the Times is writing about the use of eminent domain in New York--which was not the subject of this article.]

Today's article included these passages:

The issue was one of the first raised when Connecticut lawmakers returned to session early this month. There are bills pending in the Legislature to impose new restrictions on the use of eminent domain by local governments and to assure that displaced businesses and homeowners receive fair compensation.

(The New London project is essentially delayed, even after the Supreme Court go-ahead, because of contractual disputes and an unwillingness to forcibly remove the homeowners who sued to save their properties.)

In the New Jersey Legislature, Senator Nia H. Gill, a Democrat from Montclair who is chairwoman of the Commerce Committee, proposed a bill to outlaw the use of eminent domain to condemn residential property that is not completely run down to make room for a redevelopment project. The bill, which is pending, would require public hearings before any taking of private property to benefit a private project.

In New York, State Senator John A. DeFrancisco, a Republican, has proposed a measure similar to one in other states that would remove the right to exercise condemnation power from unelected bodies like an urban redevelopment authority or an industrial development agency.

Monday, February 20, 2006

Demolitions timeline: what do "emergency" and "immediate" mean?

What did they know and when did they know it? Did Forest City Ratner act responsibly in its plans to demolish several buildings it owns or controls? Did the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC)?

The testimony and legal filings in the court case filed by Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) and other community groups, in which state Supreme Court Justice Carol Edmead refused to overturn ESDC's approval of the demolition plans, offer a timeline to flesh out some of those questions.

The papers suggest that the terms "emergency" and "immediate" may be legal terms required to approve the demolitions, but at the same time, the actions of the parties belie the urgency suggested by the plain meaning of those terms. Otherwise, the parties might have acted more quickly and tried harder to warn the public.

In Spring 2005, Forest City Ratner was advised to apply to the ESDC to demolish the buildings as an "emergency." However, the company did not, for various reasons, make the effort for several months. On 11/7/05, LZA Technology, a respected engineering firm hired by the developer, certified that 11 buildings at five properties were in "immediate" danger. But it took the ESDC five weeks to approve the decision; during that interregnum, there was no apparent effort by the developer to warn the public.

That's not to say that Forest City Ratner has tried to knock down most of the buildings it has acquired. Indeed, a company official said in his affidavit that the developer deferred to the judgment of its consultant and withdrew plans to demolish buildings that were deemed structurally sound.

Winter 2004-05: plans emerge

According to Forest City Ratner's contract for demolition work with Gateway Demolition Corp., the environmental firm AKRF--the same firm that is now working for the ESDC--conducted environmental site assessments in April, June, and August of 2004. But the real path toward the demolitions began at the end of the year. In December, 2004, contractors conducted asbestos inspection report for the Underberg Building, at 608-620 Atlantic Avenue. (Photo by Forgotten NY.)

According to Forest City Ratner's contract for demolition work with Gateway Demolition Corp., the environmental firm AKRF--the same firm that is now working for the ESDC--conducted environmental site assessments in April, June, and August of 2004. But the real path toward the demolitions began at the end of the year. In December, 2004, contractors conducted asbestos inspection report for the Underberg Building, at 608-620 Atlantic Avenue. (Photo by Forgotten NY.)

In January or February 2005, according to an affidavit from FCR's Andrew Zlotnick, in consultation with environmental consultants at AKRF, he put together a list of buildings that appared to be so dilapidated that they would require demolition rather than maintenance. Besides consulting with staff members, the company also retained LZA Technology, "a well-known Manhattan based firm of consulting structural engineers."

According to the contract, the inspections began in January, and in February and March, demolition plans were drawn up for several buildings.

1/14/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 461 Dean Street

1/16/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 463 Dean Street

2/05: Environmental site assessments

2/10/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 585-601 Dean Street

2/15/05: Demolition specifications for 608-620 Atlantic Avenue

3/2/05: Structural due diligence survey of 461 & 463 Dean Street, and 585-601 Dean Street

3/4/05: Demolition plan for building at 585-601 Dean Street

3/7/05: Demolition plan for buildings at 461-465 Dean Street and 626 Pacific Street

Spring 2005: legal twist, MTA roadblock

Zlotnick stated: "As to some of the buildings that I had identified as potentially so hazardous as to require demolition, LZA advised me that, in its opinion, the buildings were not structurally unsound and need not be demolished. As to those

Zlotnick stated: "As to some of the buildings that I had identified as potentially so hazardous as to require demolition, LZA advised me that, in its opinion, the buildings were not structurally unsound and need not be demolished. As to those

buildings, FCRC deferred to LZA's professional judgment and decided not to proceed with demolition. Nevertheless,in the spring of 2005, FCRC had received reports from LZA recommending that six or seven buildings that FCRC had acquired or was in contract to acquire were so unsafe and structurally unsound that they should be demolished." (Right, 461 and 463 Dean Street, in a photo taken shortly after the 12/16/05 demolition announcement. There were no apparent warning signs.)

On 4/28/05, FCR issued a notice of intent to award the demolition contract and on 5/2/05, the developer listed the scope of work for demolition. However, a legal dispute arose about FCR's right to demolish the buildings. Attorney Melanie Meyers argued that FCR had the right to demolish the buildings without any ESDC review; attorney David Paget, then working for the developer (but later for ESDC), and the ESDC's Rachel Shatz said state regulations required ESDC approval. Paget suggested a solution, according to Meyers: state law exempts from the SEQRA (State Environmental Quality Act) "emergency actions that are immediately necessary on a limited and temporary basis for the protection or preservation of life, health, property or natural resources." FCR, according to Meyers, decided to submit materials to ESDC to determine that an emergency existed.

However, a roadblock arose. According to Zlotnick's affidavit, some of the structures were close to subway tunnels and could not be demolished without the MTA signing off on the process. Meyers wrote that "efforts toward demolition" halted in late spring because the Metropolitan Transportation Authority sought competitive bids for the Vanderbilt Yards. "Because of the ongoing public bidding process, there was a moratorium on any FCRC communications with the MTA and ESDC regarding the Project," she stated.

The moratorium lasted until 9/14/05, when the MTA awarded FCR the right to develop the railyard. Note that Jeffrey Baker, the attorney for Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, said in court that Bruce Ratner met twice with MTA officials, including Chairman Peter Kalikow, during that supposed interregnum.

Summer 2005: moving ahead

According to the contract, LZA continued its inspections:

6/23/05: Structural due diligence survey for 608-620 Atlantic Avenue

6/27/05 & 6/30/05: Demolition plan for buildings at 620 Pacific Street

7/6/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 620 Pacific Street

7/23/05: Structural due diligence survey for 620 Pacific Street

On 9/14/05, the MTA awarded FCR the right to develop the railyard, and thus removed the moratorium. On 9/16/05, ESDC issued a notice that it would be the lead agency for environmental review process.

Fall 2005: another look, a five-week gap

On 10/18/05, ESDC held a six-hour public scoping hearing on the project. At about the same time, FCR asked LZA to update its surveys, expressing concern that snow, ice, and other weather conditions could further damage the buildings, according to Zlotnick. On 11/2/05, a LZA engineer made a presentation, with Power Point slides, to MTA, ESDC, and FCR representatives. On 11/7/05, LZA prepared a new report on the buildings, calling their condition "an immediate threat to the preservation of life, health, and property." The next day, FCR sent the LZA report to ESDC, via FedEx. (Above, 620 and 622 Pacific Street, shortly after the 12/16/05 announcement of the demolition plans. There were no apparent warning signs.)

On 10/18/05, ESDC held a six-hour public scoping hearing on the project. At about the same time, FCR asked LZA to update its surveys, expressing concern that snow, ice, and other weather conditions could further damage the buildings, according to Zlotnick. On 11/2/05, a LZA engineer made a presentation, with Power Point slides, to MTA, ESDC, and FCR representatives. On 11/7/05, LZA prepared a new report on the buildings, calling their condition "an immediate threat to the preservation of life, health, and property." The next day, FCR sent the LZA report to ESDC, via FedEx. (Above, 620 and 622 Pacific Street, shortly after the 12/16/05 announcement of the demolition plans. There were no apparent warning signs.)

It took five weeks for the ESDC to act, but it's not clear why. The agency's Shatz said in an affidavit that there were both internal and external meetings. "After reviewing the LZA report and consulting with other senior officials at the ESDC, and our outside environmental counsel Sive Paget, I determined that an 'emergency' existed," she stated.

[Note that I wrote on 12/30/05 that "the timing of Forest City Ratner's announcement seems to have been tied less to the receipt of the report than the plans for asbestos abatement." According to the papers filed in the lawsuit, the timing related to the receipt of the ESDC's approval.]

Meanwhile, work by LZA continued, according to the contract.

11/22/05: Environmental site assessments

11/30/05: Demolition plan for building at 622 Pacific Street

On 12/1/05, FCR issued a revised scope of work for demolition, the next day revised its notice of intent to award the demolition contract. On 12/14/05, according to the contract, it again revised the scope of work for demolition.

Emergency declared

On 12/15/05, Shatz, in a memo to the ESDC's Atlantic Yards project file, concluded that "demolition of the Unsafe Structures by FCRC is an emergency action that is immediately necessary on a limited and temporary basis for the protection and preservation of life, health, and property." (The footer of the memo, curiously enough, was dated 12/5/05.) The same day, Forest City Ratner gave the New York Times an exclusive regarding its demolition plans.

On 12/16/05, ESDC sent FCR a letter declaring the demolitions to be an emergency action. The same day, when the Times story appeared, FCR issued a press release saying it would begin asbestos abatement and then demolish six buildings. (One of those buildings, 622 Pacific Street, was incorrectly listed, because LZA had not included it in its report to ESDC.) FCR also issued a demolition contract that day.

A week later, on 12/22/05, FCR again revised its notice of intent to award the demolition contract, and revised the scope of demolition work.

During the week of December 19, DDDB and local politicans asked for an opportunity to look at the buildings, with an independent engineer. Forest City Ratner initially agreed, and an inspection was scheduled for 12/20/05, including representatives of DDDB, Council Member Letitia James, and the engineer. "That inspection was cancelled by FCRC without explanation, and a subsequent inspection was scheduled for December 21st or 22nd," according to the legal filing. "However, FCRC informed DDDB that it would not be permitted to be present at the inspection and it informed Councilwoman James that she would not be permitted to bring an engineer to the inspection." James said she wouldn't visit the buildings without the engineer. "They told me that an independent review might 'slow down the process," James said.

"The question is, God forbid that a building collapses, God forbid that a falling brick hits someone in the head, or that there's a fire," FCR's Bruce Bender said, according to the 12/16/05 Times article. On the one hand, the approaching winter did present a more hazardous situation, especially since Forest City Ratner neglected to seal all the windows in its buildings. On the other hand, the concept of "emergency" had existed since the spring.

Winter 2005-06: lawsuit

In January 2006, engineer Jay Butler said in an affidavit, after reviewing the LZA report and conducting an external examination of the buildings: "Any defects to the buildings or threats to public safety appear to be consistent with conditions found at countless other buildings in New York City. Such defects can be safely stabilized with commonly-used repair measures." He acknowledged that his observations were preliminary; the LZA report said that the interiors of the structures were far more damaged than the exteriors. (Above, 585-601 Dean Street.)

In January 2006, engineer Jay Butler said in an affidavit, after reviewing the LZA report and conducting an external examination of the buildings: "Any defects to the buildings or threats to public safety appear to be consistent with conditions found at countless other buildings in New York City. Such defects can be safely stabilized with commonly-used repair measures." He acknowledged that his observations were preliminary; the LZA report said that the interiors of the structures were far more damaged than the exteriors. (Above, 585-601 Dean Street.)

On 1/18/06, DDDB and associated groups filed suit to block the demolitions and to disqualify Paget. On 2/14/06, Edmead refused to block the demolitions but did disqualify Paget. Two days later, the ESDC appealed Edmead's disqualification decision.

Note that there are five properties at issue, since a sixth building initially announced for demolition has not yet approved by the ESDC. The petitioners consider the six initially announced properties 12 buildings since one of the properties has a building behind it, and the Underberg Building is six joined structures. Subtracting that one building, five properties and 11 buildings are, according to the ESDC, approved for demolition, but Forest City Ratner must still get permits from the city Department of Buildings.

The testimony and legal filings in the court case filed by Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) and other community groups, in which state Supreme Court Justice Carol Edmead refused to overturn ESDC's approval of the demolition plans, offer a timeline to flesh out some of those questions.

The papers suggest that the terms "emergency" and "immediate" may be legal terms required to approve the demolitions, but at the same time, the actions of the parties belie the urgency suggested by the plain meaning of those terms. Otherwise, the parties might have acted more quickly and tried harder to warn the public.

In Spring 2005, Forest City Ratner was advised to apply to the ESDC to demolish the buildings as an "emergency." However, the company did not, for various reasons, make the effort for several months. On 11/7/05, LZA Technology, a respected engineering firm hired by the developer, certified that 11 buildings at five properties were in "immediate" danger. But it took the ESDC five weeks to approve the decision; during that interregnum, there was no apparent effort by the developer to warn the public.

That's not to say that Forest City Ratner has tried to knock down most of the buildings it has acquired. Indeed, a company official said in his affidavit that the developer deferred to the judgment of its consultant and withdrew plans to demolish buildings that were deemed structurally sound.

Winter 2004-05: plans emerge

According to Forest City Ratner's contract for demolition work with Gateway Demolition Corp., the environmental firm AKRF--the same firm that is now working for the ESDC--conducted environmental site assessments in April, June, and August of 2004. But the real path toward the demolitions began at the end of the year. In December, 2004, contractors conducted asbestos inspection report for the Underberg Building, at 608-620 Atlantic Avenue. (Photo by Forgotten NY.)

According to Forest City Ratner's contract for demolition work with Gateway Demolition Corp., the environmental firm AKRF--the same firm that is now working for the ESDC--conducted environmental site assessments in April, June, and August of 2004. But the real path toward the demolitions began at the end of the year. In December, 2004, contractors conducted asbestos inspection report for the Underberg Building, at 608-620 Atlantic Avenue. (Photo by Forgotten NY.)In January or February 2005, according to an affidavit from FCR's Andrew Zlotnick, in consultation with environmental consultants at AKRF, he put together a list of buildings that appared to be so dilapidated that they would require demolition rather than maintenance. Besides consulting with staff members, the company also retained LZA Technology, "a well-known Manhattan based firm of consulting structural engineers."

According to the contract, the inspections began in January, and in February and March, demolition plans were drawn up for several buildings.

1/14/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 461 Dean Street

1/16/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 463 Dean Street

2/05: Environmental site assessments

2/10/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 585-601 Dean Street

2/15/05: Demolition specifications for 608-620 Atlantic Avenue

3/2/05: Structural due diligence survey of 461 & 463 Dean Street, and 585-601 Dean Street

3/4/05: Demolition plan for building at 585-601 Dean Street

3/7/05: Demolition plan for buildings at 461-465 Dean Street and 626 Pacific Street

Spring 2005: legal twist, MTA roadblock

Zlotnick stated: "As to some of the buildings that I had identified as potentially so hazardous as to require demolition, LZA advised me that, in its opinion, the buildings were not structurally unsound and need not be demolished. As to those

Zlotnick stated: "As to some of the buildings that I had identified as potentially so hazardous as to require demolition, LZA advised me that, in its opinion, the buildings were not structurally unsound and need not be demolished. As to thosebuildings, FCRC deferred to LZA's professional judgment and decided not to proceed with demolition. Nevertheless,in the spring of 2005, FCRC had received reports from LZA recommending that six or seven buildings that FCRC had acquired or was in contract to acquire were so unsafe and structurally unsound that they should be demolished." (Right, 461 and 463 Dean Street, in a photo taken shortly after the 12/16/05 demolition announcement. There were no apparent warning signs.)

On 4/28/05, FCR issued a notice of intent to award the demolition contract and on 5/2/05, the developer listed the scope of work for demolition. However, a legal dispute arose about FCR's right to demolish the buildings. Attorney Melanie Meyers argued that FCR had the right to demolish the buildings without any ESDC review; attorney David Paget, then working for the developer (but later for ESDC), and the ESDC's Rachel Shatz said state regulations required ESDC approval. Paget suggested a solution, according to Meyers: state law exempts from the SEQRA (State Environmental Quality Act) "emergency actions that are immediately necessary on a limited and temporary basis for the protection or preservation of life, health, property or natural resources." FCR, according to Meyers, decided to submit materials to ESDC to determine that an emergency existed.

However, a roadblock arose. According to Zlotnick's affidavit, some of the structures were close to subway tunnels and could not be demolished without the MTA signing off on the process. Meyers wrote that "efforts toward demolition" halted in late spring because the Metropolitan Transportation Authority sought competitive bids for the Vanderbilt Yards. "Because of the ongoing public bidding process, there was a moratorium on any FCRC communications with the MTA and ESDC regarding the Project," she stated.

The moratorium lasted until 9/14/05, when the MTA awarded FCR the right to develop the railyard. Note that Jeffrey Baker, the attorney for Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, said in court that Bruce Ratner met twice with MTA officials, including Chairman Peter Kalikow, during that supposed interregnum.

Summer 2005: moving ahead

According to the contract, LZA continued its inspections:

6/23/05: Structural due diligence survey for 608-620 Atlantic Avenue

6/27/05 & 6/30/05: Demolition plan for buildings at 620 Pacific Street

7/6/05: Pre-demolition asbestos inspection for 620 Pacific Street

7/23/05: Structural due diligence survey for 620 Pacific Street

On 9/14/05, the MTA awarded FCR the right to develop the railyard, and thus removed the moratorium. On 9/16/05, ESDC issued a notice that it would be the lead agency for environmental review process.

Fall 2005: another look, a five-week gap

On 10/18/05, ESDC held a six-hour public scoping hearing on the project. At about the same time, FCR asked LZA to update its surveys, expressing concern that snow, ice, and other weather conditions could further damage the buildings, according to Zlotnick. On 11/2/05, a LZA engineer made a presentation, with Power Point slides, to MTA, ESDC, and FCR representatives. On 11/7/05, LZA prepared a new report on the buildings, calling their condition "an immediate threat to the preservation of life, health, and property." The next day, FCR sent the LZA report to ESDC, via FedEx. (Above, 620 and 622 Pacific Street, shortly after the 12/16/05 announcement of the demolition plans. There were no apparent warning signs.)

On 10/18/05, ESDC held a six-hour public scoping hearing on the project. At about the same time, FCR asked LZA to update its surveys, expressing concern that snow, ice, and other weather conditions could further damage the buildings, according to Zlotnick. On 11/2/05, a LZA engineer made a presentation, with Power Point slides, to MTA, ESDC, and FCR representatives. On 11/7/05, LZA prepared a new report on the buildings, calling their condition "an immediate threat to the preservation of life, health, and property." The next day, FCR sent the LZA report to ESDC, via FedEx. (Above, 620 and 622 Pacific Street, shortly after the 12/16/05 announcement of the demolition plans. There were no apparent warning signs.)It took five weeks for the ESDC to act, but it's not clear why. The agency's Shatz said in an affidavit that there were both internal and external meetings. "After reviewing the LZA report and consulting with other senior officials at the ESDC, and our outside environmental counsel Sive Paget, I determined that an 'emergency' existed," she stated.

[Note that I wrote on 12/30/05 that "the timing of Forest City Ratner's announcement seems to have been tied less to the receipt of the report than the plans for asbestos abatement." According to the papers filed in the lawsuit, the timing related to the receipt of the ESDC's approval.]

Meanwhile, work by LZA continued, according to the contract.

11/22/05: Environmental site assessments

11/30/05: Demolition plan for building at 622 Pacific Street

On 12/1/05, FCR issued a revised scope of work for demolition, the next day revised its notice of intent to award the demolition contract. On 12/14/05, according to the contract, it again revised the scope of work for demolition.

Emergency declared

On 12/15/05, Shatz, in a memo to the ESDC's Atlantic Yards project file, concluded that "demolition of the Unsafe Structures by FCRC is an emergency action that is immediately necessary on a limited and temporary basis for the protection and preservation of life, health, and property." (The footer of the memo, curiously enough, was dated 12/5/05.) The same day, Forest City Ratner gave the New York Times an exclusive regarding its demolition plans.

On 12/16/05, ESDC sent FCR a letter declaring the demolitions to be an emergency action. The same day, when the Times story appeared, FCR issued a press release saying it would begin asbestos abatement and then demolish six buildings. (One of those buildings, 622 Pacific Street, was incorrectly listed, because LZA had not included it in its report to ESDC.) FCR also issued a demolition contract that day.

A week later, on 12/22/05, FCR again revised its notice of intent to award the demolition contract, and revised the scope of demolition work.

During the week of December 19, DDDB and local politicans asked for an opportunity to look at the buildings, with an independent engineer. Forest City Ratner initially agreed, and an inspection was scheduled for 12/20/05, including representatives of DDDB, Council Member Letitia James, and the engineer. "That inspection was cancelled by FCRC without explanation, and a subsequent inspection was scheduled for December 21st or 22nd," according to the legal filing. "However, FCRC informed DDDB that it would not be permitted to be present at the inspection and it informed Councilwoman James that she would not be permitted to bring an engineer to the inspection." James said she wouldn't visit the buildings without the engineer. "They told me that an independent review might 'slow down the process," James said.

"The question is, God forbid that a building collapses, God forbid that a falling brick hits someone in the head, or that there's a fire," FCR's Bruce Bender said, according to the 12/16/05 Times article. On the one hand, the approaching winter did present a more hazardous situation, especially since Forest City Ratner neglected to seal all the windows in its buildings. On the other hand, the concept of "emergency" had existed since the spring.

Winter 2005-06: lawsuit

In January 2006, engineer Jay Butler said in an affidavit, after reviewing the LZA report and conducting an external examination of the buildings: "Any defects to the buildings or threats to public safety appear to be consistent with conditions found at countless other buildings in New York City. Such defects can be safely stabilized with commonly-used repair measures." He acknowledged that his observations were preliminary; the LZA report said that the interiors of the structures were far more damaged than the exteriors. (Above, 585-601 Dean Street.)

In January 2006, engineer Jay Butler said in an affidavit, after reviewing the LZA report and conducting an external examination of the buildings: "Any defects to the buildings or threats to public safety appear to be consistent with conditions found at countless other buildings in New York City. Such defects can be safely stabilized with commonly-used repair measures." He acknowledged that his observations were preliminary; the LZA report said that the interiors of the structures were far more damaged than the exteriors. (Above, 585-601 Dean Street.)On 1/18/06, DDDB and associated groups filed suit to block the demolitions and to disqualify Paget. On 2/14/06, Edmead refused to block the demolitions but did disqualify Paget. Two days later, the ESDC appealed Edmead's disqualification decision.

Note that there are five properties at issue, since a sixth building initially announced for demolition has not yet approved by the ESDC. The petitioners consider the six initially announced properties 12 buildings since one of the properties has a building behind it, and the Underberg Building is six joined structures. Subtracting that one building, five properties and 11 buildings are, according to the ESDC, approved for demolition, but Forest City Ratner must still get permits from the city Department of Buildings.

Saturday, February 18, 2006

ESDC appeals decision, says loss of lawyer puts Atlantic Yards project on hold

Until the decision on February 14 disqualifying a lawyer for the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) because he previously worked on the Atlantic Yards project for developer Forest City Ratner, ESDC had planned to issue the Final Scoping Document--a prelude to a Draft Environmental Impact Statement--within 30 days.

Now, with the potential loss of attorney David Paget, "the order of the court below has brought the environmental review process respecting the Atlantic Yards project--and thus the project itself--to a screeching halt, since experienced outside counsel is required for a project of this nature," said ESDC attorney Douglas Kraus in a statement filed with the appeal of Justice Carol Edmead's decision.

What about finding a new lawyer? Well, said Kraus, relatively few such qualified counsel exist, and three are already working for other parties in this case: two for Forest City Ratner and one for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. He asked for an expedited appeal "in the interest of fairness," and called for a schedule that would lead to an oral argument before the state appellate court during the week of March 6.

A factual twist in the legal case

As shown by Edmead's narrow decision upholding the ESDC's right to approve the demolitions proposed by Forest City Ratner, what's legal may remain questionable. While Edmead's disqualification of Paget may seem intuitively right to those objecting to the "collaborative" relationship between developer and state agency, it may not rest on solid legal ground. The judge herself said from the bench, "I don't doubt that the court's determination may not stand."

While the case law undoubtedly will be argued in competing memoranda of law, the memorandum initially filed by the ESDC makes the case that Edmead misread the documents in asserting that Paget was retained by ESDC in February 2005 and thus was representing both parties at the same time. Rather, Kraus argues in the memorandum, there was no such formal retainer, just the signing of a cost reiumbursement agreement, which actually occurred in February 2004.

Rather, Paget worked for Forest City Ratner through September 2005, then went to work for the state agency the next month--but never for both parties simultaneously. The issue, though, is broader: whether there is an apparent conflict of interest as well.

Edmead wrote, "The Court does not question respondents' contention that it is normal procedure for the applicant to pay for ESDC specialists. However, that does not obviate the obligation to avoid any conflict of interest"--a conflict stemming also from the "oft bottom-line, profit-making pursuits of real estate development corporations" and the "valid environmental interests of the ESDC." Since that pattern may be typical for such large development project, the appellate court must decide is whether it's inappropriate.

Now, with the potential loss of attorney David Paget, "the order of the court below has brought the environmental review process respecting the Atlantic Yards project--and thus the project itself--to a screeching halt, since experienced outside counsel is required for a project of this nature," said ESDC attorney Douglas Kraus in a statement filed with the appeal of Justice Carol Edmead's decision.

What about finding a new lawyer? Well, said Kraus, relatively few such qualified counsel exist, and three are already working for other parties in this case: two for Forest City Ratner and one for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. He asked for an expedited appeal "in the interest of fairness," and called for a schedule that would lead to an oral argument before the state appellate court during the week of March 6.

A factual twist in the legal case

As shown by Edmead's narrow decision upholding the ESDC's right to approve the demolitions proposed by Forest City Ratner, what's legal may remain questionable. While Edmead's disqualification of Paget may seem intuitively right to those objecting to the "collaborative" relationship between developer and state agency, it may not rest on solid legal ground. The judge herself said from the bench, "I don't doubt that the court's determination may not stand."

While the case law undoubtedly will be argued in competing memoranda of law, the memorandum initially filed by the ESDC makes the case that Edmead misread the documents in asserting that Paget was retained by ESDC in February 2005 and thus was representing both parties at the same time. Rather, Kraus argues in the memorandum, there was no such formal retainer, just the signing of a cost reiumbursement agreement, which actually occurred in February 2004.

Rather, Paget worked for Forest City Ratner through September 2005, then went to work for the state agency the next month--but never for both parties simultaneously. The issue, though, is broader: whether there is an apparent conflict of interest as well.

Edmead wrote, "The Court does not question respondents' contention that it is normal procedure for the applicant to pay for ESDC specialists. However, that does not obviate the obligation to avoid any conflict of interest"--a conflict stemming also from the "oft bottom-line, profit-making pursuits of real estate development corporations" and the "valid environmental interests of the ESDC." Since that pattern may be typical for such large development project, the appellate court must decide is whether it's inappropriate.