Sunday, January 08, 2006

Gehry, in Manhattan, hit with Atlantic Yards questions: “I didn’t expect this to be a thing about Brooklyn"

Architect Frank Gehry should’ve expected it, given that Brooklynites were out in force at the last public appearance he made in New York, in November, at a session of the American Institute of Architects. But Gehry seemed perturbed yesterday when three Brooklynites peppered him with questions about the proposed Atlantic Yards project he is designing for Forest City Ratner—including a challenge regarding eminent domain--and at one point he even cut off the questioning. And, whether misinformed or evasive, Gehry suggested that building a mixed-use project to accompany the arena was driven by a desire to create a harmonious urban fabric rather than--as evidence suggests--to generate revenue.

"I didn’t expect this to be a thing about Brooklyn--I guess I should’ve known better," Gehry said during the Q&A segment of his appearance at a Times Talk segment of the New York Times Arts & Leisure Weekend. Peter Krashes, president of the Dean Street Block Association, pressed on, but Gehry continued, "It’s not fair to nail me on this here. Let’s do it some other time." Most in the audience--Gehry aficionados and/or area residents unworried about Atlantic Yards--offered sustained applause, and Krashes withdrew. (Photo is from a previous interview at Columbia.)

"I didn’t expect this to be a thing about Brooklyn--I guess I should’ve known better," Gehry said during the Q&A segment of his appearance at a Times Talk segment of the New York Times Arts & Leisure Weekend. Peter Krashes, president of the Dean Street Block Association, pressed on, but Gehry continued, "It’s not fair to nail me on this here. Let’s do it some other time." Most in the audience--Gehry aficionados and/or area residents unworried about Atlantic Yards--offered sustained applause, and Krashes withdrew. (Photo is from a previous interview at Columbia.)

Maybe it was the time for such questions, given that attendees had spent $35 ($30 + service charge) for tickets to the 80-minute event at the CUNY Graduate Center in Manhattan, and that Gehry has not yet responded to invitations to meet with concerned citizens who live in or around the proposed project footprint. After the event, Krashes--who in his respectful public question noted that he had no position on the arena--got on the long line behind those seeking Gehry autographs and waited his turn. When he approached Gehry, Krashes mentioned that his group had previously sent a letter inviting the architect to a meeting.

Gehry said he would, "as soon as the guys let me," adding "talk to Stuckey"--a reference to Forest City Ratner VP Jim Stuckey.

At this point, handlers for the event ushered Gehry’s interlocutors along.

Eminent domain

During the session, Gehry had said of his projects, "If I think it got out of whack with my own principles, I’d walk away." Patti Hagan of the Prospect Heights Action Coalition, wearing a "Welcome to Ratnerville" t-shirt and a sticker saying "Eminent Domain Abuse," picked up on that. She asked, "Have any of your previous projects involved the use of eminent domain or eminent domain abuse? Does that square with your principles? And would that be enough to make you walk away from the Ratner project?"

During the session, Gehry had said of his projects, "If I think it got out of whack with my own principles, I’d walk away." Patti Hagan of the Prospect Heights Action Coalition, wearing a "Welcome to Ratnerville" t-shirt and a sticker saying "Eminent Domain Abuse," picked up on that. She asked, "Have any of your previous projects involved the use of eminent domain or eminent domain abuse? Does that square with your principles? And would that be enough to make you walk away from the Ratner project?"

"No comment," Gehry responded, to applause, though not as much as he received previously. (Gehry fans had to perform a quick calculation: it’s one thing to admire the architect, but another to endorse eminent domain.) OK, Hagan’s set of questions was loaded, but wouldn't it be worth learning Gehry’s record with eminent domain? (Photo of Gehry and Hagan meeting at the AIA session in November by Genevieve Christy, as appearing in the Brooklyn Papers article. Note another take on that article.)

Gehry, interviewed by Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff, began the wide-ranging session (billed under the rubric "Free Form") by narrating a slide show of his buildings from around the world. The last slide was from New York: the headquarters for InterActive on 11th Avenue in Chelsea that is "nearly topped out" and is expected to open at the end of the year. There were no renderings of the Atlantic Yards project, where construction may start later this year, though a new design is expected. (Ouroussoff photo from Charlie Rose interview.)

Gehry, interviewed by Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff, began the wide-ranging session (billed under the rubric "Free Form") by narrating a slide show of his buildings from around the world. The last slide was from New York: the headquarters for InterActive on 11th Avenue in Chelsea that is "nearly topped out" and is expected to open at the end of the year. There were no renderings of the Atlantic Yards project, where construction may start later this year, though a new design is expected. (Ouroussoff photo from Charlie Rose interview.)

Questions of scale

Later, when Ouroussoff brought up the Brooklyn project, he observed, "It’s the first time you’ve worked on that scale... unless you go back to really early on, when you’re talking about Rouse"—the ill-fated Santa Monica Place mall (1980) that Gehry designed, just before he broke with developer The Rouse Company, laid off nearly all his staff, and reconceptualized his career.

Gehry responded, "I did a lot of housing for FHA [Federal Housing Administration], and that kind of stuff."

Ouroussoff said, "But not quite on this scale, not at this point in your career. You're also working--"

Gehry continued, "But I’m a do-gooder, lefty type, still, so it was manna from heaven, to get that project." [Some people I spoke to thought this was a reference to Atlantic Yards and its affordable housing component; I think Gehry was still referring to the FHA work.]

Ouroussoff went on to note that Gehry is working more with developers these days and suggested, "One of the things that I think keeps your creative clock ticking is trying to put yourself in places where you don’t feel safe. Working on that scale is not a place where I assume you feel as comfortable as with some of the other projects you've been doing now for a long time."

"I’m very uncomfortable," said Gehry.

"I’m very uncomfortable," said Gehry.

"What are the challenges there?" Ouroussoff asked.

"Well, the challenges are kind of obvious," Gehry replied. "First of all it’s an empty site, it's got rail lines and all that stuff." [The New York Observer report said he "blurted" his response, but I thought it was routine.]

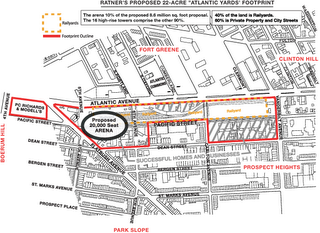

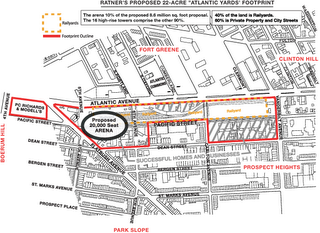

"No, it’s not," a few in the crowd shot back--and the audience seemed a bit startled. Note that the proposed site is 22 acres, including an 8.3-acre railyard. (Photo above of Dean Street row at 6th Avenue from Forgotten NY. Graphic below from Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn.)

"It’s an existing neighborhood," Gehry amended, compliant if not full of conviction. "There’s an arena, a big arena, it's like the ostrich swallowing the basketball. A lot of people want this arena, on that spot, and the company hired me to put it there. The idea of just putting an arena on that spot, in a neighborhood like that, without trying to make it part of the fabric somewhat, didn't appeal to me. And so there was a program for housing and offices and other things that had to be built for the arena to happen."

"It’s an existing neighborhood," Gehry amended, compliant if not full of conviction. "There’s an arena, a big arena, it's like the ostrich swallowing the basketball. A lot of people want this arena, on that spot, and the company hired me to put it there. The idea of just putting an arena on that spot, in a neighborhood like that, without trying to make it part of the fabric somewhat, didn't appeal to me. And so there was a program for housing and offices and other things that had to be built for the arena to happen."

Actually, Gehry had it backwards: the mixed-use complex was not driven by his esthetic response. As noted in Chapter 1 of my report, Bruce Ratner told the New York Times (A Grand Plan in Brooklyn For the Nets’ Arena Complex, 12/11/03) that the issue was economic: "This started with basketball,a Brooklyn sport," Mr. Ratner said. "This was always the site. But it became clear it was not economically viable without a real estate component."

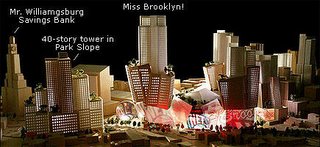

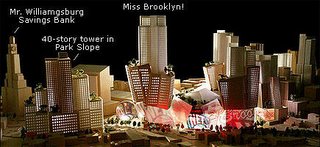

Gehry, as he has said previously, indicated that the project would shrink: "We've been playing with the scale. The pictures you saw in the New York Times [7/5/05], the way it looked--it's not that big. It’s big, but not that big. It’s coming way back, in a lot of areas, and I guess something will go public in the next few months." He didn’t offer specifics. The project was initially seen as out of scale at 7.7 million square feet and has since grown to 9.1 million square feet, so the amount of reduction must be seen in context. (Image of previously-released sketches, which should change, from New York Times via NoLandGrab.)

Gehry, as he has said previously, indicated that the project would shrink: "We've been playing with the scale. The pictures you saw in the New York Times [7/5/05], the way it looked--it's not that big. It’s big, but not that big. It’s coming way back, in a lot of areas, and I guess something will go public in the next few months." He didn’t offer specifics. The project was initially seen as out of scale at 7.7 million square feet and has since grown to 9.1 million square feet, so the amount of reduction must be seen in context. (Image of previously-released sketches, which should change, from New York Times via NoLandGrab.)

"We've tried to break down the scale as much as possible. There is a piece of

Flatbush at the corner of Atlantic where it's pretty big in relation to what's across the street. But it's the arena, and what's on the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush is in scale with the Williamsburg [Bank]."

Flatbush at the corner of Atlantic where it's pretty big in relation to what's across the street. But it's the arena, and what's on the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush is in scale with the Williamsburg [Bank]."

(To be specific, the 1929 bank is 512 feet tall, while the "Miss Brooklyn" tower, as proposed, would be 620 feet.) "If you go toward that way, contextually, it’s going to work. If you go this way, contextually, it’s a problem." It wasn't clear exactly where he was pointing, but note that the Pacific Street branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, the first Carnegie Library in Brooklyn, is just across Pacific Street from Site 5, currently the home of P.C. Richard/Modell's, where a 430-foot tower is planned. (Image from Brooklyn Public Library.)

Twenty buildings?

Gehry, who had previously said that he had asked Ratner to let other architects design parts of the project, didn’t complain yesterday but simply related that "there are some 20 buildings to be built, and the client insisted that I do them all. When he came to me, he said, 'I know you're going to try and bring all your friends in to do all the buildings, cause that's a cop-out.'... And he didn't want me to do that, he wanted me to really solve the problem, and put me on the hot seat." Twenty buildings? As of now, the project would involve an arena and 16 towers. Was Gehry simply being vague, or was he possibly referring to plans to build a new development complex, which could include new towers, on the site of Ratner’s Atlantic Center mall?

Given the challenge of building such a large project, Gehry mused, "Then you start looking at how much of this should be background, which elements should have an iconic presence, which should be in between background and iconic, and how do you orchestrate a skyline that somehow makes sense?... We’re trying, I am trying, and you’ll still hate what I do, anyway." (At this point, no questions had been asked, and the only pushback Gehry had gotten was from the few people in the crowd who knew that the proposed site isn’t empty.)

Gehry said that the site "would use a variety of materials so they don’t look like they've all been done by one person, they don't look like a project, they look like they grew over time. Then the public spaces, how to orchestrate those. And then the issue of--an arena needs bells and whistles and whoop-de-do, and then you are in a residential district and how do you orchestrate that so that the people in those apartments that we're going to build aren't plagued? If a guy comes home from work and wants to cool out, he's not barraged with imagery and bright lights. And so there's a whole bunch of sensitivities. How do you do that, how do you make it come alive for the game and solve the problem of identity for this basketball team and I hope someday a hockey team." (The Toronto-reared Gehry’s a hockey fan.)

Ouroussoff asked, "What are the limits, when you're working with a developer on that scale? What are you not allowed to do? You talked a lot about scale, about massing, about surfaces, about materials and things like that. All of those things you can do really well."

Gehry responded, "All of those things the client so far is complicit in. Up to this point, Bruce Ratner and his people have been very understanding and complicit and on board, they want that." He noted that there were then decisions on cost that are part of the development process and value engineering. "The fear or the unease for me in this, which I've talked to you about before, is: 'What is it we’re doing?' To me, when I look at my models now, it looks like a 19th century model, and that bothers me, but I don't know where to go, to be a 21st century model in this context. I got some ideas. My friends and I agonize: what would Rem [Koolhaas] do? What Zaha [Hadid] would do would look like a freeway interchange. And I haven't gone there. So if I've been holding back--'Is it right; is it wrong?"--these are the self-doubts that I have."

Ouroussoff suggested that part of that had to do with the expectations of an architect post-Bilbao. Gehry responded, "There's an expectation of what I do: 'This doesn't look like Bilbao; why are you doing this stuff that looks ordinary?' I've gotten some of that already."

Ouroussoff asked, "Is there a model beyond Jane Jacobs in terms of urban planning?" Would Ratner let Gehry work on the 'internal social organism' of the project? "Will the developer let you play with those things, the way you were able to with your own house?"

"No," Gehry said, citing in-house marketing people and architects at Forest City Ratner. "They do apartment layouts. We tweak them, but we can't really make a big architectural statement... We can influence them, make sure they are in the right places with the right views... but it’s fairly conventional...Like I read in the paper today, [Santiago] Calatrava is doing with his townhouse. You can’t go there. Not with this--at this level. But, you can make the experience from arrival, the front door, all the way through it, the way the elevator's designed, the lighting in the halls, it doesn’t have to be like going into the, um, the morgue. So it can be humanized. And I try to do that."

Urban design in question

When the Q&A began, Michael Decker praised Bilbao and said he cheered for Gehry when he got an honorary degree at Brandeis--"and now I live in Brooklyn."

"Here we go," Gehry said ruefully.

Decker observed, "I don't think changing the massing is going to disguise the massing of the project. I'm interested in what you were talking about, about being a do-gooder leftist, and how you square that with the superblock, with the towers, the shrouded park...?"

I'm interested in what you were talking about, about being a do-gooder leftist, and how you square that with the superblock, with the towers, the shrouded park...?"

Gehry responded, "Bruce Ratner is also politically like me. We’ve discussed that a lot. We’re trying to live within our own principles on those issues. I think the scale issue is the only problem, we're out of whack with that."

Decker followed up, citing broken street walls, "the buildings plunked down and separated from the neighborhood in a very non-Jane Jacobs way, that it's towers in a park all over again."

"It isn't," Gehry said.

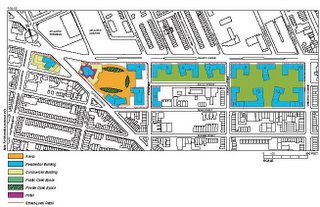

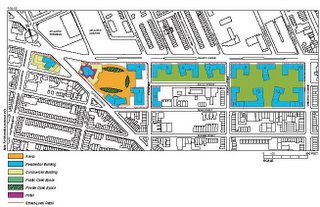

Ouroussoff clarified, "It's not a superblock, first of all. There are two parts of the project... there's a part at Flatbush and Atlantic, which is the arena, which is surrounded by a grouping of either three or four towers. Then if you go back from there, there's a series of apartment buildings along Atlantic. Those are broken up into a series of different masses, different pieces--as opposed to a superblock that would be either 'here are the towers at the center of the project,' or it would be a long continuous building."

Decker responded by citing "the street demapping." Indeed, while the project--as Ouroussoff pointed out--would not be one monolithic set of towers, a superblock has more to do with closing streets. A superblock, according to the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus, "[d]esignates very large, usually residential, city blocks often formed by consolidating several smaller blocks and often barred to through traffic and crossed by pedestrian walks." Note that Pacific Street would be closed between Vanderbilt and Carlton avenues, and between Sixth and Flatbush avenues. Fifth Avenue would be closed between Flatbush and Atlantic avenue. Architect Jonathan Cohn comments on his blog, "No amount of open views in the interior of a superblock will make the ground plane function like a watched public street. A real street functions not only for access to adjacent built form but connects and integrates the immediate area into the circulation systems of adjacent areas."

Gehry asked Decker, "How would you do it, ideally?"

Decker responded, "In my ideal world, you would build only on the railyards. There would be no eminent domain. It would be three 25-, 35-story tall buildings, a central courtyard, New York typology... and I think you'd have a vibrant, active place." (Left unsaid was that an arena cannot be built solely on the railyard, and the scale of the project has been driven in part by the need to include affordable housing, which itself was needed to gain political support.)

Gehry continued, "That's what we're doing, one building after another along the avenue, with a ground floor that's culturally..." .

"They're certainly not continuous," Decker responded. "They're separate buildings."

Ouroussoff interjected, perhaps sensing dismay in the audience that the session had tilted toward Brooklyn, "It raises an interesting question. What is your role as an architect, because developments of that same scale are going to happen, and the architect has no control over that. That's not the architect's job."

"He can turn it down," Gehry observed.

Ouroussoff continued, "You either walk away from it, or you see if there's something actually you can bring to the project."

"I try to do that, but I think if it got out of whack with my own principles, I would walk away," Gehry said. "It's not there yet, but maybe you think I should be there." Several in the crowd chuckled.

Then Krashes, announcing himself as representative of the block association on Dean Street, which forms the southern boundary of the project, observed that a lot of the discussion had been about housing as sculpture, form and mass. "We don't want you to turn your back on us, as an architect. What we want you to do is explain your role as a planner," Krashes said. He noted that five city blocks would be turned into one project and streets would be demapped for the arena, "which is logical, from one point of view, if you want the arena," and also "to create open space for very large buildings that do ring the open space. And the justification for removing that street is to provide open space for the public, it's not a park. It's open space that's privately owned. It's going to be at the service, really, of the buildings ringing the project."

"It’s designed as publicly accessible on all sides," Gehry replied.

Krashes continued, noting that the demapping of streets has implications for traffic. Gehry responded, "There are--I've got engineers and traffic experts and city planning, and we've been working with all of those people in the development of this. None of this has been done willfully, without being vetted by the experts."

Krashes tried to follow up, but Gehry, and the applauding crowd, cut off the discussion. (Several people asked non-Brooklyn questions during the Q&A, and Hagan's question did come after Krashes' question.)

Early in the program, when showing a slide of the acclaimed Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, Gehry observed wryly, "The only problem with this building is: I use it. Usually my buildings are far enough away that I don’t have to live with them. Every time I go to a concert I see everything I would do and change." From the questions voiced at this forum, some Brooklynites are hoping he’ll at least give them face time.

"I didn’t expect this to be a thing about Brooklyn--I guess I should’ve known better," Gehry said during the Q&A segment of his appearance at a Times Talk segment of the New York Times Arts & Leisure Weekend. Peter Krashes, president of the Dean Street Block Association, pressed on, but Gehry continued, "It’s not fair to nail me on this here. Let’s do it some other time." Most in the audience--Gehry aficionados and/or area residents unworried about Atlantic Yards--offered sustained applause, and Krashes withdrew. (Photo is from a previous interview at Columbia.)

"I didn’t expect this to be a thing about Brooklyn--I guess I should’ve known better," Gehry said during the Q&A segment of his appearance at a Times Talk segment of the New York Times Arts & Leisure Weekend. Peter Krashes, president of the Dean Street Block Association, pressed on, but Gehry continued, "It’s not fair to nail me on this here. Let’s do it some other time." Most in the audience--Gehry aficionados and/or area residents unworried about Atlantic Yards--offered sustained applause, and Krashes withdrew. (Photo is from a previous interview at Columbia.)Maybe it was the time for such questions, given that attendees had spent $35 ($30 + service charge) for tickets to the 80-minute event at the CUNY Graduate Center in Manhattan, and that Gehry has not yet responded to invitations to meet with concerned citizens who live in or around the proposed project footprint. After the event, Krashes--who in his respectful public question noted that he had no position on the arena--got on the long line behind those seeking Gehry autographs and waited his turn. When he approached Gehry, Krashes mentioned that his group had previously sent a letter inviting the architect to a meeting.

Gehry said he would, "as soon as the guys let me," adding "talk to Stuckey"--a reference to Forest City Ratner VP Jim Stuckey.

At this point, handlers for the event ushered Gehry’s interlocutors along.

Eminent domain

During the session, Gehry had said of his projects, "If I think it got out of whack with my own principles, I’d walk away." Patti Hagan of the Prospect Heights Action Coalition, wearing a "Welcome to Ratnerville" t-shirt and a sticker saying "Eminent Domain Abuse," picked up on that. She asked, "Have any of your previous projects involved the use of eminent domain or eminent domain abuse? Does that square with your principles? And would that be enough to make you walk away from the Ratner project?"

During the session, Gehry had said of his projects, "If I think it got out of whack with my own principles, I’d walk away." Patti Hagan of the Prospect Heights Action Coalition, wearing a "Welcome to Ratnerville" t-shirt and a sticker saying "Eminent Domain Abuse," picked up on that. She asked, "Have any of your previous projects involved the use of eminent domain or eminent domain abuse? Does that square with your principles? And would that be enough to make you walk away from the Ratner project?""No comment," Gehry responded, to applause, though not as much as he received previously. (Gehry fans had to perform a quick calculation: it’s one thing to admire the architect, but another to endorse eminent domain.) OK, Hagan’s set of questions was loaded, but wouldn't it be worth learning Gehry’s record with eminent domain? (Photo of Gehry and Hagan meeting at the AIA session in November by Genevieve Christy, as appearing in the Brooklyn Papers article. Note another take on that article.)

Gehry, interviewed by Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff, began the wide-ranging session (billed under the rubric "Free Form") by narrating a slide show of his buildings from around the world. The last slide was from New York: the headquarters for InterActive on 11th Avenue in Chelsea that is "nearly topped out" and is expected to open at the end of the year. There were no renderings of the Atlantic Yards project, where construction may start later this year, though a new design is expected. (Ouroussoff photo from Charlie Rose interview.)

Gehry, interviewed by Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff, began the wide-ranging session (billed under the rubric "Free Form") by narrating a slide show of his buildings from around the world. The last slide was from New York: the headquarters for InterActive on 11th Avenue in Chelsea that is "nearly topped out" and is expected to open at the end of the year. There were no renderings of the Atlantic Yards project, where construction may start later this year, though a new design is expected. (Ouroussoff photo from Charlie Rose interview.)Questions of scale

Later, when Ouroussoff brought up the Brooklyn project, he observed, "It’s the first time you’ve worked on that scale... unless you go back to really early on, when you’re talking about Rouse"—the ill-fated Santa Monica Place mall (1980) that Gehry designed, just before he broke with developer The Rouse Company, laid off nearly all his staff, and reconceptualized his career.

Gehry responded, "I did a lot of housing for FHA [Federal Housing Administration], and that kind of stuff."

Ouroussoff said, "But not quite on this scale, not at this point in your career. You're also working--"

Gehry continued, "But I’m a do-gooder, lefty type, still, so it was manna from heaven, to get that project." [Some people I spoke to thought this was a reference to Atlantic Yards and its affordable housing component; I think Gehry was still referring to the FHA work.]

Ouroussoff went on to note that Gehry is working more with developers these days and suggested, "One of the things that I think keeps your creative clock ticking is trying to put yourself in places where you don’t feel safe. Working on that scale is not a place where I assume you feel as comfortable as with some of the other projects you've been doing now for a long time."

"I’m very uncomfortable," said Gehry.

"I’m very uncomfortable," said Gehry."What are the challenges there?" Ouroussoff asked.

"Well, the challenges are kind of obvious," Gehry replied. "First of all it’s an empty site, it's got rail lines and all that stuff." [The New York Observer report said he "blurted" his response, but I thought it was routine.]

"No, it’s not," a few in the crowd shot back--and the audience seemed a bit startled. Note that the proposed site is 22 acres, including an 8.3-acre railyard. (Photo above of Dean Street row at 6th Avenue from Forgotten NY. Graphic below from Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn.)

"It’s an existing neighborhood," Gehry amended, compliant if not full of conviction. "There’s an arena, a big arena, it's like the ostrich swallowing the basketball. A lot of people want this arena, on that spot, and the company hired me to put it there. The idea of just putting an arena on that spot, in a neighborhood like that, without trying to make it part of the fabric somewhat, didn't appeal to me. And so there was a program for housing and offices and other things that had to be built for the arena to happen."

"It’s an existing neighborhood," Gehry amended, compliant if not full of conviction. "There’s an arena, a big arena, it's like the ostrich swallowing the basketball. A lot of people want this arena, on that spot, and the company hired me to put it there. The idea of just putting an arena on that spot, in a neighborhood like that, without trying to make it part of the fabric somewhat, didn't appeal to me. And so there was a program for housing and offices and other things that had to be built for the arena to happen."Actually, Gehry had it backwards: the mixed-use complex was not driven by his esthetic response. As noted in Chapter 1 of my report, Bruce Ratner told the New York Times (A Grand Plan in Brooklyn For the Nets’ Arena Complex, 12/11/03) that the issue was economic: "This started with basketball,a Brooklyn sport," Mr. Ratner said. "This was always the site. But it became clear it was not economically viable without a real estate component."

Gehry, as he has said previously, indicated that the project would shrink: "We've been playing with the scale. The pictures you saw in the New York Times [7/5/05], the way it looked--it's not that big. It’s big, but not that big. It’s coming way back, in a lot of areas, and I guess something will go public in the next few months." He didn’t offer specifics. The project was initially seen as out of scale at 7.7 million square feet and has since grown to 9.1 million square feet, so the amount of reduction must be seen in context. (Image of previously-released sketches, which should change, from New York Times via NoLandGrab.)

Gehry, as he has said previously, indicated that the project would shrink: "We've been playing with the scale. The pictures you saw in the New York Times [7/5/05], the way it looked--it's not that big. It’s big, but not that big. It’s coming way back, in a lot of areas, and I guess something will go public in the next few months." He didn’t offer specifics. The project was initially seen as out of scale at 7.7 million square feet and has since grown to 9.1 million square feet, so the amount of reduction must be seen in context. (Image of previously-released sketches, which should change, from New York Times via NoLandGrab.)"We've tried to break down the scale as much as possible. There is a piece of

Flatbush at the corner of Atlantic where it's pretty big in relation to what's across the street. But it's the arena, and what's on the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush is in scale with the Williamsburg [Bank]."

Flatbush at the corner of Atlantic where it's pretty big in relation to what's across the street. But it's the arena, and what's on the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush is in scale with the Williamsburg [Bank]."(To be specific, the 1929 bank is 512 feet tall, while the "Miss Brooklyn" tower, as proposed, would be 620 feet.) "If you go toward that way, contextually, it’s going to work. If you go this way, contextually, it’s a problem." It wasn't clear exactly where he was pointing, but note that the Pacific Street branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, the first Carnegie Library in Brooklyn, is just across Pacific Street from Site 5, currently the home of P.C. Richard/Modell's, where a 430-foot tower is planned. (Image from Brooklyn Public Library.)

Twenty buildings?

Gehry, who had previously said that he had asked Ratner to let other architects design parts of the project, didn’t complain yesterday but simply related that "there are some 20 buildings to be built, and the client insisted that I do them all. When he came to me, he said, 'I know you're going to try and bring all your friends in to do all the buildings, cause that's a cop-out.'... And he didn't want me to do that, he wanted me to really solve the problem, and put me on the hot seat." Twenty buildings? As of now, the project would involve an arena and 16 towers. Was Gehry simply being vague, or was he possibly referring to plans to build a new development complex, which could include new towers, on the site of Ratner’s Atlantic Center mall?

Given the challenge of building such a large project, Gehry mused, "Then you start looking at how much of this should be background, which elements should have an iconic presence, which should be in between background and iconic, and how do you orchestrate a skyline that somehow makes sense?... We’re trying, I am trying, and you’ll still hate what I do, anyway." (At this point, no questions had been asked, and the only pushback Gehry had gotten was from the few people in the crowd who knew that the proposed site isn’t empty.)

Gehry said that the site "would use a variety of materials so they don’t look like they've all been done by one person, they don't look like a project, they look like they grew over time. Then the public spaces, how to orchestrate those. And then the issue of--an arena needs bells and whistles and whoop-de-do, and then you are in a residential district and how do you orchestrate that so that the people in those apartments that we're going to build aren't plagued? If a guy comes home from work and wants to cool out, he's not barraged with imagery and bright lights. And so there's a whole bunch of sensitivities. How do you do that, how do you make it come alive for the game and solve the problem of identity for this basketball team and I hope someday a hockey team." (The Toronto-reared Gehry’s a hockey fan.)

Ouroussoff asked, "What are the limits, when you're working with a developer on that scale? What are you not allowed to do? You talked a lot about scale, about massing, about surfaces, about materials and things like that. All of those things you can do really well."

Gehry responded, "All of those things the client so far is complicit in. Up to this point, Bruce Ratner and his people have been very understanding and complicit and on board, they want that." He noted that there were then decisions on cost that are part of the development process and value engineering. "The fear or the unease for me in this, which I've talked to you about before, is: 'What is it we’re doing?' To me, when I look at my models now, it looks like a 19th century model, and that bothers me, but I don't know where to go, to be a 21st century model in this context. I got some ideas. My friends and I agonize: what would Rem [Koolhaas] do? What Zaha [Hadid] would do would look like a freeway interchange. And I haven't gone there. So if I've been holding back--'Is it right; is it wrong?"--these are the self-doubts that I have."

Ouroussoff suggested that part of that had to do with the expectations of an architect post-Bilbao. Gehry responded, "There's an expectation of what I do: 'This doesn't look like Bilbao; why are you doing this stuff that looks ordinary?' I've gotten some of that already."

Ouroussoff asked, "Is there a model beyond Jane Jacobs in terms of urban planning?" Would Ratner let Gehry work on the 'internal social organism' of the project? "Will the developer let you play with those things, the way you were able to with your own house?"

"No," Gehry said, citing in-house marketing people and architects at Forest City Ratner. "They do apartment layouts. We tweak them, but we can't really make a big architectural statement... We can influence them, make sure they are in the right places with the right views... but it’s fairly conventional...Like I read in the paper today, [Santiago] Calatrava is doing with his townhouse. You can’t go there. Not with this--at this level. But, you can make the experience from arrival, the front door, all the way through it, the way the elevator's designed, the lighting in the halls, it doesn’t have to be like going into the, um, the morgue. So it can be humanized. And I try to do that."

Urban design in question

When the Q&A began, Michael Decker praised Bilbao and said he cheered for Gehry when he got an honorary degree at Brandeis--"and now I live in Brooklyn."

"Here we go," Gehry said ruefully.

Decker observed, "I don't think changing the massing is going to disguise the massing of the project.

I'm interested in what you were talking about, about being a do-gooder leftist, and how you square that with the superblock, with the towers, the shrouded park...?"

I'm interested in what you were talking about, about being a do-gooder leftist, and how you square that with the superblock, with the towers, the shrouded park...?"Gehry responded, "Bruce Ratner is also politically like me. We’ve discussed that a lot. We’re trying to live within our own principles on those issues. I think the scale issue is the only problem, we're out of whack with that."

Decker followed up, citing broken street walls, "the buildings plunked down and separated from the neighborhood in a very non-Jane Jacobs way, that it's towers in a park all over again."

"It isn't," Gehry said.

Ouroussoff clarified, "It's not a superblock, first of all. There are two parts of the project... there's a part at Flatbush and Atlantic, which is the arena, which is surrounded by a grouping of either three or four towers. Then if you go back from there, there's a series of apartment buildings along Atlantic. Those are broken up into a series of different masses, different pieces--as opposed to a superblock that would be either 'here are the towers at the center of the project,' or it would be a long continuous building."

Decker responded by citing "the street demapping." Indeed, while the project--as Ouroussoff pointed out--would not be one monolithic set of towers, a superblock has more to do with closing streets. A superblock, according to the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus, "[d]esignates very large, usually residential, city blocks often formed by consolidating several smaller blocks and often barred to through traffic and crossed by pedestrian walks." Note that Pacific Street would be closed between Vanderbilt and Carlton avenues, and between Sixth and Flatbush avenues. Fifth Avenue would be closed between Flatbush and Atlantic avenue. Architect Jonathan Cohn comments on his blog, "No amount of open views in the interior of a superblock will make the ground plane function like a watched public street. A real street functions not only for access to adjacent built form but connects and integrates the immediate area into the circulation systems of adjacent areas."

Gehry asked Decker, "How would you do it, ideally?"

Decker responded, "In my ideal world, you would build only on the railyards. There would be no eminent domain. It would be three 25-, 35-story tall buildings, a central courtyard, New York typology... and I think you'd have a vibrant, active place." (Left unsaid was that an arena cannot be built solely on the railyard, and the scale of the project has been driven in part by the need to include affordable housing, which itself was needed to gain political support.)

Gehry continued, "That's what we're doing, one building after another along the avenue, with a ground floor that's culturally..." .

"They're certainly not continuous," Decker responded. "They're separate buildings."

Ouroussoff interjected, perhaps sensing dismay in the audience that the session had tilted toward Brooklyn, "It raises an interesting question. What is your role as an architect, because developments of that same scale are going to happen, and the architect has no control over that. That's not the architect's job."

"He can turn it down," Gehry observed.

Ouroussoff continued, "You either walk away from it, or you see if there's something actually you can bring to the project."

"I try to do that, but I think if it got out of whack with my own principles, I would walk away," Gehry said. "It's not there yet, but maybe you think I should be there." Several in the crowd chuckled.

Then Krashes, announcing himself as representative of the block association on Dean Street, which forms the southern boundary of the project, observed that a lot of the discussion had been about housing as sculpture, form and mass. "We don't want you to turn your back on us, as an architect. What we want you to do is explain your role as a planner," Krashes said. He noted that five city blocks would be turned into one project and streets would be demapped for the arena, "which is logical, from one point of view, if you want the arena," and also "to create open space for very large buildings that do ring the open space. And the justification for removing that street is to provide open space for the public, it's not a park. It's open space that's privately owned. It's going to be at the service, really, of the buildings ringing the project."

"It’s designed as publicly accessible on all sides," Gehry replied.

Krashes continued, noting that the demapping of streets has implications for traffic. Gehry responded, "There are--I've got engineers and traffic experts and city planning, and we've been working with all of those people in the development of this. None of this has been done willfully, without being vetted by the experts."

Krashes tried to follow up, but Gehry, and the applauding crowd, cut off the discussion. (Several people asked non-Brooklyn questions during the Q&A, and Hagan's question did come after Krashes' question.)

Early in the program, when showing a slide of the acclaimed Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, Gehry observed wryly, "The only problem with this building is: I use it. Usually my buildings are far enough away that I don’t have to live with them. Every time I go to a concert I see everything I would do and change." From the questions voiced at this forum, some Brooklynites are hoping he’ll at least give them face time.