Thursday, December 29, 2005

"Unfamiliar territory": Times critic Ouroussoff on Gehry, Ratner, and the challenge in Brooklyn

On the Charlie Rose show on PBS last night, the host interviewed New York Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff (below, photo from Charlie Rose web site) about a range of issues and, at one point, the talk turned to Brooklyn. The critic offered some cautionary words about the relationship between architects and developers, and wondered whether Bruce Ratner would give Gehry more autonomy.

Charlie Rose: Brooklyn. Frank Gehry has a chance to change a city, literally, of four million people, which is the fourth or fifth largest city in America. Will that happen? [Note: Brooklyn has about 2.5 million people.]

Nicolai Ouroussoff:This goes back to what we've been talking about. One of the things that's fascinating to me about Brooklyn, and all the projects that Frank and also Renzo Piano are doing for Bruce Ratner, because Piano's designing the New York Times Tower.

CR: On Times Square.

NO: On Times Square, yeah.

CR: 42nd is it, or where?

NO: 41st, across from Port Authority, on Eighth Avenue. You can see it, it's going up now.

But I think that one of the things that's happened, that's very important in the past few years, that all of a sudden, because of the cachet that architects can bring to projects, that you have a lot of developers that suddenly are interested in working with the kinds of architects they never would've touched four or five years ago. And the question then becomes: what are these architects allowed to do? Are they only there to be able to kind of decorate buildings, to make them more appealing to the public, or to raise their value basically and put more money in the pockets of their developers? Or are they actually there to rethink the way most of this work is done? And I think, if you look at Frank Gehry's project for example for Bruce Ratner in Brooklyn, where he's dealing with an arena and a lot of residential space. We all know that Frank Gehry can make very pretty forms. He has an incredible sense of scale, of massing, he'll make the buildings somehow relate to what's around them, he understands context.

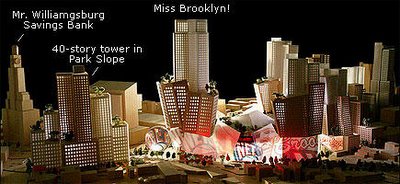

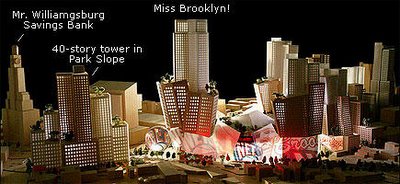

[The original plan, announced in December 2003, albeit without a close-up of the arena and the buildings around it, which were the only ones fleshed out.]

The question is, for me, is he going to be able to deal with the things that traditionally developers might not let him play with. For example, the social organizations of the apartments inside. The relationship of the project to the context around it, in terms of the ground plan. I think Frank comes out of a tradition, in terms of urban planning, that in a lot of ways is very conservative. He's never built on this scale before. And I think he's now getting into a kind of unfamiliar territory, in terms of the scale he's working with. One of the things I think happens when you're working with developers is that, y'know, the kinds of architects they're used to working with--they come up with a scheme and what the developer does is, he takes a scheme, and then he builds it.

And a talented architect, all of the work happens between here and here. You start with an idea and then it's at that moment that you struggle with it, that you realize that you start turning it into something, then it takes on a life of its own, you have to kind of let it go where it's going to go. And the question is: can these architects operate that way in the context of a developer like Bruce Ratner, and to me that's really important, because if you're able to make that system work and change that system, then you start to really affect the world in a very important way.

Andersen on Gehry, Gehry on Brooklyn

In the 11/28/05 issue of New York magazine, in an article headlined Delirious New York, Kurt Andersen noted that the reason for hiring Gehry (right, photo from Columbia University web site) was in part political:

Ratner isn’t spending 15 percent extra on these new buildings simply because he wants to underwrite cool design. He understands that in Brooklyn, just as his quotas of apartments for poor people and construction jobs for women and minorities were ways of winning over key constituencies, hiring Gehry was politics by other means, sure to please the city’s BAM-loving chattering class. “The spirit of what you say,” Ratner agrees when I posit this theory, “is accurate.”

And Ratner acknowledged to Andersen the distinction Ouroussoff pointed out: "I have to blame myself [for the Atlantic Center mall]. I’ve been talking for ten years about trying to use ‘design architects’ instead of 'developer architects.'"

But would the buildings of Atlantic Yards project "somehow relate to what's around them," as Ourossoff suggested? Andersen suggested they might not, but it was worth it: The skewed, cartoony angles of the buildings, which range from 20 to 60 stories, would in one fell swoop create a second, sui generis Brooklyn skyline encompassing the familiar, phallic old Williamsburgh Bank Building. Note, however, that that July 2005 design below may be supplanted by a new one. [Addenda courtesy of Naparstek.com]

A couple of letter-writers to New York magazine, however, were more critical. Stuart Schrader wrote: Like Bruce Ratner’s previous developments in Brooklyn, the Atlantic Yards stadium complex is not going to seamlessly merge a new development with an existing and vital cityscape. It seems totally appropriate, then, that Bruce Ratner would choose an architect whose buildings are rootless, equally out of place wherever they are erected, always supplanting on-the-ground urban realities with whimsical promises of a future that never quite arrives.

And what does Gehry think? Speaking to an audience at Columbia University on October 31, he said he had succeeded in getting the developer to agree to scale back chunks of the project (note that I originally wrote, based on the Columbia News Service report below, that Gehry wanted the project scaled back but Ratner has not yet announced doing so); that Brooklynites expect only brownstone scale (not quite; the community-developed Unity Plan for the Vanderbilt Yard envisions high-rise buildings, though not 40-60 stories, like some at Atlantic Yards); and that he's "brought all kinds of people in" to help him get it right (that's admirable, but could some of those people be concerned locals?).

Columbia's news service reported:

While best known for his shimmering forms like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, and the Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, the Toronto-born Gehry, now 76, views himself as an urban planner, whose buildings should enhance their surroundings. "I'm a do-gooder," he said. "I see architecture as a service."

But as people in Brooklyn expect the borough to be all "brownstones and tree-lined streets," Gehry's project has met with opposition from the community. "You can't do that with a project of this size," he said, adding that he had asked the developer, Bruce Ratner, to scale back the project several times.

Meanwhile, he hasn't convinced Ratner to do something else: bring in other architects to design parts of the project, to ensure a variety of styles. "He wanted to be able to deal with one person, so he refused," Gehry said.

Faced with the challenge of designing the entire project on his own, Gehry decided to develop a "design hierarchy," where several "iconic towers" will be surrounded by "background buildings."

But the dilemma, he said, is that the background buildings end up looking ordinary, like standard-issue housing projects. "Sometimes I think I should be less polite," he said -- implying that life would be easier if his buildings were all attention-getters.

"I'm very insecure about it," Gehry said of the Brooklyn project. "I've brought all kinds of people in to beat me up, because I want to get it right."

Charlie Rose: Brooklyn. Frank Gehry has a chance to change a city, literally, of four million people, which is the fourth or fifth largest city in America. Will that happen? [Note: Brooklyn has about 2.5 million people.]

Nicolai Ouroussoff:This goes back to what we've been talking about. One of the things that's fascinating to me about Brooklyn, and all the projects that Frank and also Renzo Piano are doing for Bruce Ratner, because Piano's designing the New York Times Tower.

CR: On Times Square.

NO: On Times Square, yeah.

CR: 42nd is it, or where?

NO: 41st, across from Port Authority, on Eighth Avenue. You can see it, it's going up now.

But I think that one of the things that's happened, that's very important in the past few years, that all of a sudden, because of the cachet that architects can bring to projects, that you have a lot of developers that suddenly are interested in working with the kinds of architects they never would've touched four or five years ago. And the question then becomes: what are these architects allowed to do? Are they only there to be able to kind of decorate buildings, to make them more appealing to the public, or to raise their value basically and put more money in the pockets of their developers? Or are they actually there to rethink the way most of this work is done? And I think, if you look at Frank Gehry's project for example for Bruce Ratner in Brooklyn, where he's dealing with an arena and a lot of residential space. We all know that Frank Gehry can make very pretty forms. He has an incredible sense of scale, of massing, he'll make the buildings somehow relate to what's around them, he understands context.

[The original plan, announced in December 2003, albeit without a close-up of the arena and the buildings around it, which were the only ones fleshed out.]

The question is, for me, is he going to be able to deal with the things that traditionally developers might not let him play with. For example, the social organizations of the apartments inside. The relationship of the project to the context around it, in terms of the ground plan. I think Frank comes out of a tradition, in terms of urban planning, that in a lot of ways is very conservative. He's never built on this scale before. And I think he's now getting into a kind of unfamiliar territory, in terms of the scale he's working with. One of the things I think happens when you're working with developers is that, y'know, the kinds of architects they're used to working with--they come up with a scheme and what the developer does is, he takes a scheme, and then he builds it.

And a talented architect, all of the work happens between here and here. You start with an idea and then it's at that moment that you struggle with it, that you realize that you start turning it into something, then it takes on a life of its own, you have to kind of let it go where it's going to go. And the question is: can these architects operate that way in the context of a developer like Bruce Ratner, and to me that's really important, because if you're able to make that system work and change that system, then you start to really affect the world in a very important way.

Andersen on Gehry, Gehry on Brooklyn

In the 11/28/05 issue of New York magazine, in an article headlined Delirious New York, Kurt Andersen noted that the reason for hiring Gehry (right, photo from Columbia University web site) was in part political:

Ratner isn’t spending 15 percent extra on these new buildings simply because he wants to underwrite cool design. He understands that in Brooklyn, just as his quotas of apartments for poor people and construction jobs for women and minorities were ways of winning over key constituencies, hiring Gehry was politics by other means, sure to please the city’s BAM-loving chattering class. “The spirit of what you say,” Ratner agrees when I posit this theory, “is accurate.”

And Ratner acknowledged to Andersen the distinction Ouroussoff pointed out: "I have to blame myself [for the Atlantic Center mall]. I’ve been talking for ten years about trying to use ‘design architects’ instead of 'developer architects.'"

But would the buildings of Atlantic Yards project "somehow relate to what's around them," as Ourossoff suggested? Andersen suggested they might not, but it was worth it: The skewed, cartoony angles of the buildings, which range from 20 to 60 stories, would in one fell swoop create a second, sui generis Brooklyn skyline encompassing the familiar, phallic old Williamsburgh Bank Building. Note, however, that that July 2005 design below may be supplanted by a new one. [Addenda courtesy of Naparstek.com]

A couple of letter-writers to New York magazine, however, were more critical. Stuart Schrader wrote: Like Bruce Ratner’s previous developments in Brooklyn, the Atlantic Yards stadium complex is not going to seamlessly merge a new development with an existing and vital cityscape. It seems totally appropriate, then, that Bruce Ratner would choose an architect whose buildings are rootless, equally out of place wherever they are erected, always supplanting on-the-ground urban realities with whimsical promises of a future that never quite arrives.

And what does Gehry think? Speaking to an audience at Columbia University on October 31, he said he had succeeded in getting the developer to agree to scale back chunks of the project (note that I originally wrote, based on the Columbia News Service report below, that Gehry wanted the project scaled back but Ratner has not yet announced doing so); that Brooklynites expect only brownstone scale (not quite; the community-developed Unity Plan for the Vanderbilt Yard envisions high-rise buildings, though not 40-60 stories, like some at Atlantic Yards); and that he's "brought all kinds of people in" to help him get it right (that's admirable, but could some of those people be concerned locals?).

Columbia's news service reported:

While best known for his shimmering forms like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, and the Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, the Toronto-born Gehry, now 76, views himself as an urban planner, whose buildings should enhance their surroundings. "I'm a do-gooder," he said. "I see architecture as a service."

But as people in Brooklyn expect the borough to be all "brownstones and tree-lined streets," Gehry's project has met with opposition from the community. "You can't do that with a project of this size," he said, adding that he had asked the developer, Bruce Ratner, to scale back the project several times.

Meanwhile, he hasn't convinced Ratner to do something else: bring in other architects to design parts of the project, to ensure a variety of styles. "He wanted to be able to deal with one person, so he refused," Gehry said.

Faced with the challenge of designing the entire project on his own, Gehry decided to develop a "design hierarchy," where several "iconic towers" will be surrounded by "background buildings."

But the dilemma, he said, is that the background buildings end up looking ordinary, like standard-issue housing projects. "Sometimes I think I should be less polite," he said -- implying that life would be easier if his buildings were all attention-getters.

"I'm very insecure about it," Gehry said of the Brooklyn project. "I've brought all kinds of people in to beat me up, because I want to get it right."