Saturday, December 31, 2005

"Struggling" Gehry on "out of scale" project: "If it turns out great, that's what's right"

Internationally acclaimed architect Frank Gehry told an audience at Columbia University two months ago that the Atlantic Yards project, which he called "out of scale with the existing area," is such a struggle that he sometimes wants to "jump off the Brooklyn Bridge." A guest on the 10/31/05 "Citizen: The Campus Talk Show," Gehry also revealed that developer Forest City Ratner has in fact agreed to his requests to scale down the project--something FCR has not publicly disclosed, and something unclear in the Columbia News Service report on the talk--though he didn't describe the amount of the reduction, which is a contentious issue.

Internationally acclaimed architect Frank Gehry told an audience at Columbia University two months ago that the Atlantic Yards project, which he called "out of scale with the existing area," is such a struggle that he sometimes wants to "jump off the Brooklyn Bridge." A guest on the 10/31/05 "Citizen: The Campus Talk Show," Gehry also revealed that developer Forest City Ratner has in fact agreed to his requests to scale down the project--something FCR has not publicly disclosed, and something unclear in the Columbia News Service report on the talk--though he didn't describe the amount of the reduction, which is a contentious issue.Gehry acknowledged that Forest City Ratner's history is that "they haven't" been "interested in doing something special," but now "they have been very fastidious in supporting the things that I think are important." He acknowledged that the scale was driven by the developer, but said, "the developers have been very accepting of my pushback. And so we’ve taken chunks of it away, actually, to bring it down into scale." Gehry also observed that he normally would've brought in five other architects to ensure that the complex "doesn’t look like a project," but the client said no.

Gehry, who described himself as "a do-gooder, liberal," said he was trying to design the project "within a very open dialogue with the people who are involved," but acknowledged that success on the project was subjective: "What’s right is, if it turns out great, that’s what’s right." Indeed, though Gehry comes off as an earnest, well-meaning fellow, it's apparently not his role to be worried about a planning process that urban affairs expert Tom Angotti calls "all backwards." Note that Gehry also characterized Ratner as a fellow "liberal, do-gooder" in the 7/25/05 New York Observer; others, like Cooper Union's Fred Siegel, have called Ratner "master of the subsidy."

Despite Gehry's expressions of anxiety, he professed relatively little dismay that about the "not very many" buildings that would be razed, "because that was a given to me."He said that "when we started, there were a few buildings that were going to be kept, and we worked around them, and that felt better to me, to be able to do that, but they disappeared." It's unclear what he meant by that--did they disappear from the preservation effort (probably) or disappear because they were torn down? The project was in fact designed around the recently converted Newswalk condo, while two other buildings--the former Spalding factory (right, thanks to Forgotten NY) and the Atlantic Arts building--are slated to fall.

Despite Gehry's expressions of anxiety, he professed relatively little dismay that about the "not very many" buildings that would be razed, "because that was a given to me."He said that "when we started, there were a few buildings that were going to be kept, and we worked around them, and that felt better to me, to be able to do that, but they disappeared." It's unclear what he meant by that--did they disappear from the preservation effort (probably) or disappear because they were torn down? The project was in fact designed around the recently converted Newswalk condo, while two other buildings--the former Spalding factory (right, thanks to Forgotten NY) and the Atlantic Arts building--are slated to fall. Gehry described the section of Prospect Heights--a name he didn't use--at issue as "a neighborhood that’s not very well-defined," which is not inaccurate, given that Pacific Street has a industrial buildings converted to condos, empty buildings, and a homeless shelter, while Dean Street (below, thanks to Forgotten NY) has both row houses and industrial buildings (and another homeless shelter). But Gehry characterized critics with a broad brush: "[T]here is a constituency of people that live there who fantasize this Brooklyn as brownstones and Court Street and Carroll Gardens and all that, which isn’t on this site." Well, for one thing, there are row houses in the proposed project footprint, so his "new neighborhood" would hardly be placed on a tabula rasa. Also, the community-developed Unity Plan for the Vanderbilt Yard envisions high-rise buildings, though not 40-60 stories, like some at Atlantic Yards. Why would Gehry mention Carroll Gardens and its major thoroughfare, Court Street, when project critics are far more likely to come from Prospect Heights and adjacent rowhouse neighborhoods like Fort Greene and Park Slope? Maybe because his daughter lives there.

Gehry described the section of Prospect Heights--a name he didn't use--at issue as "a neighborhood that’s not very well-defined," which is not inaccurate, given that Pacific Street has a industrial buildings converted to condos, empty buildings, and a homeless shelter, while Dean Street (below, thanks to Forgotten NY) has both row houses and industrial buildings (and another homeless shelter). But Gehry characterized critics with a broad brush: "[T]here is a constituency of people that live there who fantasize this Brooklyn as brownstones and Court Street and Carroll Gardens and all that, which isn’t on this site." Well, for one thing, there are row houses in the proposed project footprint, so his "new neighborhood" would hardly be placed on a tabula rasa. Also, the community-developed Unity Plan for the Vanderbilt Yard envisions high-rise buildings, though not 40-60 stories, like some at Atlantic Yards. Why would Gehry mention Carroll Gardens and its major thoroughfare, Court Street, when project critics are far more likely to come from Prospect Heights and adjacent rowhouse neighborhoods like Fort Greene and Park Slope? Maybe because his daughter lives there. The hour-long show covered a number of issues, and included slides shown to the audience of various projects. Notable is that Gehry himself brought up Atlantic Yards rather than follow the lead of host Kelvin Sealey. The issue was obviously fresh in his mind.

Early in the show (approximately 3:30) Sealey asked his guest about his early professional roots.

FG: I worked in a lot of offices in Europe and in L.A., and was interested in city planning. I’m a do-gooder, liberal, and I still am. I’m not a Bushie. I’m respectful, but… barely.

KS: Can we go to your design education?

FG: Architecture, as I developed as an architect, I considered a service. We were meeting with clients--you’re hired to do a project and you bring the best you can do the table and deliver the best that you can do.

A bit later in the show (at about 15:00), Sealey asked about the Gehry Residence, the architect's renovation of his Santa Monica home.

FG: This is a middle class neighborhood, and I think of myself as a member of that class, so to speak. And I was trying to find my identity in that neighborhood. I think it is pushy in the neighborhood, there was a backlash….Now it’s settled down and it’s probably worth more than any house on the block, and you can sell popcorn there on the weekends, students come around after all these years, so I guess something’s going on.

KS: Something’s going on. I want to go to one more slide before going to the film.

Here's where Gehry kept going.

FG: But it does bring up the issue, which I’m struggling with now in Brooklyn, a lot. We’re about to build, probably, an arena for the Nets, and a lot of housing. And everything we’re building is out of scale with the existing area. And the struggle is: It’s a neighborhood that’s not very well-defined, but there is a constituency of people that live there who fantasize this Brooklyn as brownstones and Court Street and Carroll Gardens and all that, which isn’t on this site. But in their mind, Brooklyn should continue to be like that. But this part of Brooklyn isn’t going to be like that. And so this developer’s is interested in doing something special. Their history is, they haven’t, but now they want to. I took them at their word, and they have been very fastidious in supporting the things that I think are important.

The struggle is, you end up with sort of a pseudo-19th century scheme—how do you take that into the 21st century, what makes it different, how do you make a complex that doesn’t look like a project even though one architect’s doing it? Normally I would’ve brought in five other architects, but one of the requirements of this client is that I do it. And so, how do you make buildings that fit, how do you make a new skyline, how do you develop a scale at the ground level, how do you create the opportunities, how do you fit an arena that at night brings a lot of people in, and is bright and sparky and a party, and the during the day what does that mean.

Those are all the issues, and they’re similar to the issues of my house, just at a bigger scale. I have a sense of responsibility to deliver something that’s a good neighbor. So I’m caught in this thing. And it’s a wonderful, scary place to be, I tell you. I have sleepless nights about it. I some days look at the project and think I can’t do it, I can’t, I go back and forth. I’m very insecure about it. I’ve brought all kinds of people in to criticize it, beat me up, do whatever, because I want to get it right. But it is that kind of issue.

KS: You bring up a number of issues… one in particularly concerns unbuilding. Some portion of the land that your structures will go on currently have buildings, is that correct?

FG: Not very many.

KS: Not very many. But to the extent of whatever is there, be they rail yards or a few brownstones or whatever is there, there’s a certain amount of unbuilding. I’m wondering if, when you think of your designs, you think about an unbuilding process?

FG: No, because that was a given to me, I had nothing to say or do about that about that process, it was given to me. I suppose some of the buildings--when we started, there were a few buildings that were going to be kept, and we worked around them, and that felt better to me, to be able to do that, but they disappeared.

During the Q&A session near the end of the show (at about 48:00), the subject returned to Brooklyn, and Gehry's second sentence, about "who's right," was a lot less clear than his conclusion.

Q: You mentioned in talking about your project in Brooklyn that you wanted to get it right. I wonder if you could tell us what you think it would mean to get it right in Brooklyn?

FG: God…Solomon, where are you now? [Solomon was the slide operator for the event] Getting it right is ephemeral, of course, because it’s who’s right is right. But I’m looking for something, I’m looking for something that makes a new neighborhood in a historic town that nee—that deserves something special for it. Because this is a big, an extraordinarily important project, and it’s all on my head, as they say. And a lot of responsibility, and a lot of anxiety, I must say, about it. There are days when I want to jump off the Brooklyn Bridge, but--because a lot of people are watching.

And the scale of the project is bigger than anything around it. And that’s the driving—it has to be in order to be accomplished. I’ve been pushing back. The developers have been very accepting of my pushback. And so we’ve taken chunks of it away, actually, to bring it down into scale, to integrate it with whatever the existing fabric is there and then finding a way, in brick and metal and glass, maybe precast, a language that can work in that area that’ll feel like a very special place and since there’s so many buildings, the thought of finding a hierarchy was important to me, that there would be certain iconic pieces and a lot of background buildings, so there’s a lot of very just simple buildings, blocky. I look at it sometimes and I say, well, that looks like a lot of stuff that’s already there. And then I wonder, am I being too polite? So there’s an anxiety about that.

In the end, I have to be responsible for it and stand up and say, I believe this is the way we should do it. And it’s that kind of back-and-forth struggle with the people that are working on it with me and the client. It’s all out on the table. We talk about it, like I’m just talking about it. I’m not trying to pull the wool over anybody’s eyes. I’m trying to do it within a very open dialogue with the people who are involved. What’s right is, if it turns out great, that’s what’s right.

Friday, December 30, 2005

A five-week wait, a Times exclusive, and an unwelcome engineer: the strategy behind Forest City Ratner's demolition plans

Remember this date: 11/7/05. It's key to the story of Forest City Ratner's plan to demolish six buildings in the footprint of the proposed Atlantic Yards complex. It's the date of the engineer's report to FCR that declared the buildings "an immediate threat to the preservation of life, health, and property." (The report describes sagging floors and water damage that threaten the integrity of the buildings, notwithstanding any apparent sturdiness from an outside view. Photos of the damaged interiors are contained in the report.) That means that Forest City Ratner, which announced its plan to the New York Times five weeks later, on 12/15/05 for coverage the next day, wasn't in the hugest hurry--though now the developer has nixed an independent review because it would "slow down the process."

Note that the report linked above was not initially released by Forest City Ratner when the story broke, but was provided only after requests by local elected officials and Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn. Photos below of the garage buildings at 620 and 622 Pacific Street were taken 12/18/05--it's not clear when or why windows were left open. Oddly, the Forest City Ratner press release said that 622 Pacific Street, the single-story building, was among "the six buildings which have been determined by LZA Technology to be unsafe." However, the report linked above doesn't mention 622 Pacific.

"The question is, God forbid that a building collapses, God forbid that a falling brick hits someone in the head, or that there's a fire," FCR's Bruce Bender told the Times. But if people were in imminent danger, why didn't the developer make an announcement immediately after the Nov. 7 report, or put more signs on the buildings? No press outlet has raised this question, but the timing of Forest City Ratner's announcement seems to have been tied less to the receipt of the report than the plans for asbestos abatement that were to begin a few days later. [Addendum 2/20/06: papers filed in the legal case show that Forest City Ratner's delayed its announcement only until the Empire State Development Corporation approved the demolition plans.]

Well, Forest City Ratner might say it had to get its asbestos abatement and demolition plans in place, including the identification of minority contractors, though apparently it has not yet applied for all the necessary permits. But the timing of the company's announcement deserves a closer look. FCR apparently gave the New York Times an exclusive, as it has done in the past, such as the 7/5/05 front-page article (Instant Skyline Added to Brooklyn Arena Plan) that introduced Frank Gehry's revised architectural sketches.

Why give the Times an exclusive? (A Forest City Ratner press release was dated 12/16/05, the date the Times story appeared.) Perhaps because the Times's audience, including policymakers, is the key audience as the Atlantic Yards plan makes its way through review by the Empire State Development Corporation. Perhaps because the Times has more space than the tabloids. Perhaps because a general public announcement might have led to more coverage, especially in the Brooklyn Papers, as noted below. Perhaps because the Times, while certainly providing more thorough coverage in recent months, has nonetheless given Forest City Ratner the benefit of the doubt in two long articles, on changes in the plan and the developer's community strategy.

Also, by announcing its decision to the Times on a Thursday (for Friday coverage), and by announcing it to the press at large a day later, Forest City Ratner could be sure that the story would not be covered immediately by the often-critical Brooklyn Paper weekly chain, which appears on Fridays (but has a Saturday publication date). [Addendum 2/20/06: The timing is more likely linked simply to the 12/15/05 decision by the Empire State Development Corporation.] And a Friday announcement would meet the deadline of the generally less-critical Courier-Life weekly chain, which appears on Saturdays (but has a Monday publication date). Indeed, the Courier-Life story included the Forest City Ratner press release, virtually verbatim, delivered just as the paper was going to press. (Note that the article is dated 12/16/05, which was apparently the day it was posted on the web, but the print issue is dated 12/19/05.)

The story continued to develop. On 12/19/05, a Daily News story headlined Plan to flatten 6 bldgs. ripped reported that City Council member Letitia James, along with fellow project critics state Senator Velmanette Montgomery and Representative Major Owens, would ask for a tour of the buildings with an independent engineer. (The building below, in two photos, is at 585 Dean Street--from the outside, it looks more stable than the Underberg building further below, though the engineer's report describes interior damage in both.) The Daily News reported a complicating fact not part of the Forest City Ratner press release or the Times story: the developer signed contracts regarding the buildings at issue from March to June 2004. (The Times described the properties as "newly acquired.") That leaves open the question of "developer's blight"--whether and how much the buildings deteriorated while under Forest City Ratner's control. The engineer's report cites water infiltration, the nature of the construction, and the age of the buildings.

The Daily News reported a complicating fact not part of the Forest City Ratner press release or the Times story: the developer signed contracts regarding the buildings at issue from March to June 2004. (The Times described the properties as "newly acquired.") That leaves open the question of "developer's blight"--whether and how much the buildings deteriorated while under Forest City Ratner's control. The engineer's report cites water infiltration, the nature of the construction, and the age of the buildings.  As Owens said in a press release issued on 12/22/05: "Ratner has owned many of these properties for over one year. Some of the damage sustained by these buildings took place after Ratner bought them. And we all know Ratner is trying to say this is a ‘blighted’ area so he can have the state seize properties for him using eminent domain. Simply put, the area is not 'blighted.' Real estate values in the footprint have risen at the same rate or faster than the rest of Brooklyn."

As Owens said in a press release issued on 12/22/05: "Ratner has owned many of these properties for over one year. Some of the damage sustained by these buildings took place after Ratner bought them. And we all know Ratner is trying to say this is a ‘blighted’ area so he can have the state seize properties for him using eminent domain. Simply put, the area is not 'blighted.' Real estate values in the footprint have risen at the same rate or faster than the rest of Brooklyn."

James also offered an unsupported quote to the Daily News: "I know these buildings, and some of them are as sound as the Empire State Building." But the bigger question is: would an outside engineer reach the same conclusions as the firm hired by Forest City Ratner?

We still don't know.

In a 12/22/05 article headlined RATNER 'RAZES' STAKES, the New York Post reported that James, Montgomery, and Owens decided not to tour the structures after the developer refused to allow the engineer to accompany them. After James's office issued a press release on 12/22/05, the Daily News, in a 12/23/05 article headlined Ratner nixes checks of Yards site bldgs., filled in the detail that Forest City Ratner had initially agreed to the request :

:

Originally, a Ratner executive approved a request from City Councilwoman Letitia James (WFP-Prospect Heights) to let her bring an independent engineer into the buildings on Dean St. and Atlantic Ave.

But in a reversal yesterday, another Ratner official barred the engineer - who had agreed to do the inspection for free - and said only elected officials could take the tour.

"It looks like they're trying to hide something," said James. "It looks like they're going forward with creating blight in the community."

James was more cautious in her comments: James conceded the Underberg Building [above, at 608-620 Atlantic Ave., photo from Forgotten NY] should be demolished, but said claims of decay at the Dean St. buildings are "questionable."

Architect Jonathan Cohn, in his Brooklyn Views blog, also raises questions about the buildings at 461 and 463 Dean Street, based on an outside view. (A photo from his 12/18/05 blog is at left.) James said of Forest City Ratner in a press release: "They told me that an independent review might 'slow down the process,'" said Council Member James. "I find this irresponsible, and overtly in contempt of the state environmental review process. We want to know what they are trying to hide by not letting us in. I have requested the Department of Buildings issue no permits until an analysis is done by someone not paid by Ratner."

Architect Jonathan Cohn, in his Brooklyn Views blog, also raises questions about the buildings at 461 and 463 Dean Street, based on an outside view. (A photo from his 12/18/05 blog is at left.) James said of Forest City Ratner in a press release: "They told me that an independent review might 'slow down the process,'" said Council Member James. "I find this irresponsible, and overtly in contempt of the state environmental review process. We want to know what they are trying to hide by not letting us in. I have requested the Department of Buildings issue no permits until an analysis is done by someone not paid by Ratner."

Left unsaid is that the five week gap between the engineer's report and the Forest City Ratner announcement could have offered more time for such an independent review.

The press release apparently came too late for the article in the 12/24/05 Brooklyn Papers, headlined DEMOLITION MAN: Ratner preps Atlantic Yards site, which mentioned local officials' criticisms, but not the developer's denial of the request to have an engineer tour the buildings. The follow-up in the Courier-Life chain, headlined Ratner Itches to Level Buildings, did address the developer's denial of the request, but not the company's flip-flop. (The article is dated 12/23/05, but the issue is 12/26/05.) Rather, company spokesman Joe DePlasco criticized James for her "Empire State Building" comment, which suggested inconsistency on her part.

So what's next? According to the 12/31/05 edition of the Brooklyn Papers, in an article headlined James and Ratner: 2 heads ’a’ buttin’, James said she was asking the city to refuse to issue demolition permits, but Ratner’s spokesman Joe DePlasco said "the relevant agencies" have been convinced. DePlasco muddied the waters by saying that that James and the other critical elected officials "were invited to tour the structures with the licensed engineer who wrote the reports, but they said no." This seems like an example of DePlasco's "Changing the Subject" tactic, since the independent engineer could have come along and would not have delayed the process significantly. (The 11/7/05 LZA Technology report was based significantly on a field visit just a few days earlier, on 11/1/05.) As the Brooklyn Papers reported: DePlasco also pointed out that if the buildings were to collapse and injure someone, everyone would again be screaming for the head of Bruce Ratner.

Again, if the issue was public safety, why did that report wait five weeks?

Note that the report linked above was not initially released by Forest City Ratner when the story broke, but was provided only after requests by local elected officials and Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn. Photos below of the garage buildings at 620 and 622 Pacific Street were taken 12/18/05--it's not clear when or why windows were left open. Oddly, the Forest City Ratner press release said that 622 Pacific Street, the single-story building, was among "the six buildings which have been determined by LZA Technology to be unsafe." However, the report linked above doesn't mention 622 Pacific.

"The question is, God forbid that a building collapses, God forbid that a falling brick hits someone in the head, or that there's a fire," FCR's Bruce Bender told the Times. But if people were in imminent danger, why didn't the developer make an announcement immediately after the Nov. 7 report, or put more signs on the buildings? No press outlet has raised this question, but the timing of Forest City Ratner's announcement seems to have been tied less to the receipt of the report than the plans for asbestos abatement that were to begin a few days later. [Addendum 2/20/06: papers filed in the legal case show that Forest City Ratner's delayed its announcement only until the Empire State Development Corporation approved the demolition plans.]

Well, Forest City Ratner might say it had to get its asbestos abatement and demolition plans in place, including the identification of minority contractors, though apparently it has not yet applied for all the necessary permits. But the timing of the company's announcement deserves a closer look. FCR apparently gave the New York Times an exclusive, as it has done in the past, such as the 7/5/05 front-page article (Instant Skyline Added to Brooklyn Arena Plan) that introduced Frank Gehry's revised architectural sketches.

Why give the Times an exclusive? (A Forest City Ratner press release was dated 12/16/05, the date the Times story appeared.) Perhaps because the Times's audience, including policymakers, is the key audience as the Atlantic Yards plan makes its way through review by the Empire State Development Corporation. Perhaps because the Times has more space than the tabloids. Perhaps because a general public announcement might have led to more coverage, especially in the Brooklyn Papers, as noted below. Perhaps because the Times, while certainly providing more thorough coverage in recent months, has nonetheless given Forest City Ratner the benefit of the doubt in two long articles, on changes in the plan and the developer's community strategy.

Also, by announcing its decision to the Times on a Thursday (for Friday coverage), and by announcing it to the press at large a day later, Forest City Ratner could be sure that the story would not be covered immediately by the often-critical Brooklyn Paper weekly chain, which appears on Fridays (but has a Saturday publication date). [Addendum 2/20/06: The timing is more likely linked simply to the 12/15/05 decision by the Empire State Development Corporation.] And a Friday announcement would meet the deadline of the generally less-critical Courier-Life weekly chain, which appears on Saturdays (but has a Monday publication date). Indeed, the Courier-Life story included the Forest City Ratner press release, virtually verbatim, delivered just as the paper was going to press. (Note that the article is dated 12/16/05, which was apparently the day it was posted on the web, but the print issue is dated 12/19/05.)

The story continued to develop. On 12/19/05, a Daily News story headlined Plan to flatten 6 bldgs. ripped reported that City Council member Letitia James, along with fellow project critics state Senator Velmanette Montgomery and Representative Major Owens, would ask for a tour of the buildings with an independent engineer. (The building below, in two photos, is at 585 Dean Street--from the outside, it looks more stable than the Underberg building further below, though the engineer's report describes interior damage in both.)

The Daily News reported a complicating fact not part of the Forest City Ratner press release or the Times story: the developer signed contracts regarding the buildings at issue from March to June 2004. (The Times described the properties as "newly acquired.") That leaves open the question of "developer's blight"--whether and how much the buildings deteriorated while under Forest City Ratner's control. The engineer's report cites water infiltration, the nature of the construction, and the age of the buildings.

The Daily News reported a complicating fact not part of the Forest City Ratner press release or the Times story: the developer signed contracts regarding the buildings at issue from March to June 2004. (The Times described the properties as "newly acquired.") That leaves open the question of "developer's blight"--whether and how much the buildings deteriorated while under Forest City Ratner's control. The engineer's report cites water infiltration, the nature of the construction, and the age of the buildings.  As Owens said in a press release issued on 12/22/05: "Ratner has owned many of these properties for over one year. Some of the damage sustained by these buildings took place after Ratner bought them. And we all know Ratner is trying to say this is a ‘blighted’ area so he can have the state seize properties for him using eminent domain. Simply put, the area is not 'blighted.' Real estate values in the footprint have risen at the same rate or faster than the rest of Brooklyn."

As Owens said in a press release issued on 12/22/05: "Ratner has owned many of these properties for over one year. Some of the damage sustained by these buildings took place after Ratner bought them. And we all know Ratner is trying to say this is a ‘blighted’ area so he can have the state seize properties for him using eminent domain. Simply put, the area is not 'blighted.' Real estate values in the footprint have risen at the same rate or faster than the rest of Brooklyn."James also offered an unsupported quote to the Daily News: "I know these buildings, and some of them are as sound as the Empire State Building." But the bigger question is: would an outside engineer reach the same conclusions as the firm hired by Forest City Ratner?

We still don't know.

In a 12/22/05 article headlined RATNER 'RAZES' STAKES, the New York Post reported that James, Montgomery, and Owens decided not to tour the structures after the developer refused to allow the engineer to accompany them. After James's office issued a press release on 12/22/05, the Daily News, in a 12/23/05 article headlined Ratner nixes checks of Yards site bldgs., filled in the detail that Forest City Ratner had initially agreed to the request

:

:Originally, a Ratner executive approved a request from City Councilwoman Letitia James (WFP-Prospect Heights) to let her bring an independent engineer into the buildings on Dean St. and Atlantic Ave.

But in a reversal yesterday, another Ratner official barred the engineer - who had agreed to do the inspection for free - and said only elected officials could take the tour.

"It looks like they're trying to hide something," said James. "It looks like they're going forward with creating blight in the community."

James was more cautious in her comments: James conceded the Underberg Building [above, at 608-620 Atlantic Ave., photo from Forgotten NY] should be demolished, but said claims of decay at the Dean St. buildings are "questionable."

Architect Jonathan Cohn, in his Brooklyn Views blog, also raises questions about the buildings at 461 and 463 Dean Street, based on an outside view. (A photo from his 12/18/05 blog is at left.) James said of Forest City Ratner in a press release: "They told me that an independent review might 'slow down the process,'" said Council Member James. "I find this irresponsible, and overtly in contempt of the state environmental review process. We want to know what they are trying to hide by not letting us in. I have requested the Department of Buildings issue no permits until an analysis is done by someone not paid by Ratner."

Architect Jonathan Cohn, in his Brooklyn Views blog, also raises questions about the buildings at 461 and 463 Dean Street, based on an outside view. (A photo from his 12/18/05 blog is at left.) James said of Forest City Ratner in a press release: "They told me that an independent review might 'slow down the process,'" said Council Member James. "I find this irresponsible, and overtly in contempt of the state environmental review process. We want to know what they are trying to hide by not letting us in. I have requested the Department of Buildings issue no permits until an analysis is done by someone not paid by Ratner."Left unsaid is that the five week gap between the engineer's report and the Forest City Ratner announcement could have offered more time for such an independent review.

The press release apparently came too late for the article in the 12/24/05 Brooklyn Papers, headlined DEMOLITION MAN: Ratner preps Atlantic Yards site, which mentioned local officials' criticisms, but not the developer's denial of the request to have an engineer tour the buildings. The follow-up in the Courier-Life chain, headlined Ratner Itches to Level Buildings, did address the developer's denial of the request, but not the company's flip-flop. (The article is dated 12/23/05, but the issue is 12/26/05.) Rather, company spokesman Joe DePlasco criticized James for her "Empire State Building" comment, which suggested inconsistency on her part.

So what's next? According to the 12/31/05 edition of the Brooklyn Papers, in an article headlined James and Ratner: 2 heads ’a’ buttin’, James said she was asking the city to refuse to issue demolition permits, but Ratner’s spokesman Joe DePlasco said "the relevant agencies" have been convinced. DePlasco muddied the waters by saying that that James and the other critical elected officials "were invited to tour the structures with the licensed engineer who wrote the reports, but they said no." This seems like an example of DePlasco's "Changing the Subject" tactic, since the independent engineer could have come along and would not have delayed the process significantly. (The 11/7/05 LZA Technology report was based significantly on a field visit just a few days earlier, on 11/1/05.) As the Brooklyn Papers reported: DePlasco also pointed out that if the buildings were to collapse and injure someone, everyone would again be screaming for the head of Bruce Ratner.

Again, if the issue was public safety, why did that report wait five weeks?

Thursday, December 29, 2005

"Unfamiliar territory": Times critic Ouroussoff on Gehry, Ratner, and the challenge in Brooklyn

On the Charlie Rose show on PBS last night, the host interviewed New York Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff (below, photo from Charlie Rose web site) about a range of issues and, at one point, the talk turned to Brooklyn. The critic offered some cautionary words about the relationship between architects and developers, and wondered whether Bruce Ratner would give Gehry more autonomy.

Charlie Rose: Brooklyn. Frank Gehry has a chance to change a city, literally, of four million people, which is the fourth or fifth largest city in America. Will that happen? [Note: Brooklyn has about 2.5 million people.]

Nicolai Ouroussoff:This goes back to what we've been talking about. One of the things that's fascinating to me about Brooklyn, and all the projects that Frank and also Renzo Piano are doing for Bruce Ratner, because Piano's designing the New York Times Tower.

CR: On Times Square.

NO: On Times Square, yeah.

CR: 42nd is it, or where?

NO: 41st, across from Port Authority, on Eighth Avenue. You can see it, it's going up now.

But I think that one of the things that's happened, that's very important in the past few years, that all of a sudden, because of the cachet that architects can bring to projects, that you have a lot of developers that suddenly are interested in working with the kinds of architects they never would've touched four or five years ago. And the question then becomes: what are these architects allowed to do? Are they only there to be able to kind of decorate buildings, to make them more appealing to the public, or to raise their value basically and put more money in the pockets of their developers? Or are they actually there to rethink the way most of this work is done? And I think, if you look at Frank Gehry's project for example for Bruce Ratner in Brooklyn, where he's dealing with an arena and a lot of residential space. We all know that Frank Gehry can make very pretty forms. He has an incredible sense of scale, of massing, he'll make the buildings somehow relate to what's around them, he understands context.

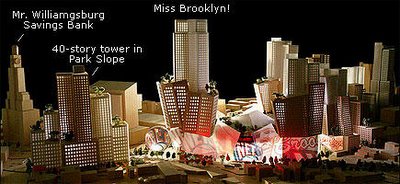

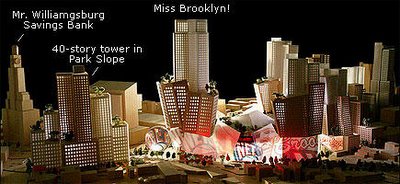

[The original plan, announced in December 2003, albeit without a close-up of the arena and the buildings around it, which were the only ones fleshed out.]

The question is, for me, is he going to be able to deal with the things that traditionally developers might not let him play with. For example, the social organizations of the apartments inside. The relationship of the project to the context around it, in terms of the ground plan. I think Frank comes out of a tradition, in terms of urban planning, that in a lot of ways is very conservative. He's never built on this scale before. And I think he's now getting into a kind of unfamiliar territory, in terms of the scale he's working with. One of the things I think happens when you're working with developers is that, y'know, the kinds of architects they're used to working with--they come up with a scheme and what the developer does is, he takes a scheme, and then he builds it.

And a talented architect, all of the work happens between here and here. You start with an idea and then it's at that moment that you struggle with it, that you realize that you start turning it into something, then it takes on a life of its own, you have to kind of let it go where it's going to go. And the question is: can these architects operate that way in the context of a developer like Bruce Ratner, and to me that's really important, because if you're able to make that system work and change that system, then you start to really affect the world in a very important way.

Andersen on Gehry, Gehry on Brooklyn

In the 11/28/05 issue of New York magazine, in an article headlined Delirious New York, Kurt Andersen noted that the reason for hiring Gehry (right, photo from Columbia University web site) was in part political:

Ratner isn’t spending 15 percent extra on these new buildings simply because he wants to underwrite cool design. He understands that in Brooklyn, just as his quotas of apartments for poor people and construction jobs for women and minorities were ways of winning over key constituencies, hiring Gehry was politics by other means, sure to please the city’s BAM-loving chattering class. “The spirit of what you say,” Ratner agrees when I posit this theory, “is accurate.”

And Ratner acknowledged to Andersen the distinction Ouroussoff pointed out: "I have to blame myself [for the Atlantic Center mall]. I’ve been talking for ten years about trying to use ‘design architects’ instead of 'developer architects.'"

But would the buildings of Atlantic Yards project "somehow relate to what's around them," as Ourossoff suggested? Andersen suggested they might not, but it was worth it: The skewed, cartoony angles of the buildings, which range from 20 to 60 stories, would in one fell swoop create a second, sui generis Brooklyn skyline encompassing the familiar, phallic old Williamsburgh Bank Building. Note, however, that that July 2005 design below may be supplanted by a new one. [Addenda courtesy of Naparstek.com]

A couple of letter-writers to New York magazine, however, were more critical. Stuart Schrader wrote: Like Bruce Ratner’s previous developments in Brooklyn, the Atlantic Yards stadium complex is not going to seamlessly merge a new development with an existing and vital cityscape. It seems totally appropriate, then, that Bruce Ratner would choose an architect whose buildings are rootless, equally out of place wherever they are erected, always supplanting on-the-ground urban realities with whimsical promises of a future that never quite arrives.

And what does Gehry think? Speaking to an audience at Columbia University on October 31, he said he had succeeded in getting the developer to agree to scale back chunks of the project (note that I originally wrote, based on the Columbia News Service report below, that Gehry wanted the project scaled back but Ratner has not yet announced doing so); that Brooklynites expect only brownstone scale (not quite; the community-developed Unity Plan for the Vanderbilt Yard envisions high-rise buildings, though not 40-60 stories, like some at Atlantic Yards); and that he's "brought all kinds of people in" to help him get it right (that's admirable, but could some of those people be concerned locals?).

Columbia's news service reported:

While best known for his shimmering forms like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, and the Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, the Toronto-born Gehry, now 76, views himself as an urban planner, whose buildings should enhance their surroundings. "I'm a do-gooder," he said. "I see architecture as a service."

But as people in Brooklyn expect the borough to be all "brownstones and tree-lined streets," Gehry's project has met with opposition from the community. "You can't do that with a project of this size," he said, adding that he had asked the developer, Bruce Ratner, to scale back the project several times.

Meanwhile, he hasn't convinced Ratner to do something else: bring in other architects to design parts of the project, to ensure a variety of styles. "He wanted to be able to deal with one person, so he refused," Gehry said.

Faced with the challenge of designing the entire project on his own, Gehry decided to develop a "design hierarchy," where several "iconic towers" will be surrounded by "background buildings."

But the dilemma, he said, is that the background buildings end up looking ordinary, like standard-issue housing projects. "Sometimes I think I should be less polite," he said -- implying that life would be easier if his buildings were all attention-getters.

"I'm very insecure about it," Gehry said of the Brooklyn project. "I've brought all kinds of people in to beat me up, because I want to get it right."

Charlie Rose: Brooklyn. Frank Gehry has a chance to change a city, literally, of four million people, which is the fourth or fifth largest city in America. Will that happen? [Note: Brooklyn has about 2.5 million people.]

Nicolai Ouroussoff:This goes back to what we've been talking about. One of the things that's fascinating to me about Brooklyn, and all the projects that Frank and also Renzo Piano are doing for Bruce Ratner, because Piano's designing the New York Times Tower.

CR: On Times Square.

NO: On Times Square, yeah.

CR: 42nd is it, or where?

NO: 41st, across from Port Authority, on Eighth Avenue. You can see it, it's going up now.

But I think that one of the things that's happened, that's very important in the past few years, that all of a sudden, because of the cachet that architects can bring to projects, that you have a lot of developers that suddenly are interested in working with the kinds of architects they never would've touched four or five years ago. And the question then becomes: what are these architects allowed to do? Are they only there to be able to kind of decorate buildings, to make them more appealing to the public, or to raise their value basically and put more money in the pockets of their developers? Or are they actually there to rethink the way most of this work is done? And I think, if you look at Frank Gehry's project for example for Bruce Ratner in Brooklyn, where he's dealing with an arena and a lot of residential space. We all know that Frank Gehry can make very pretty forms. He has an incredible sense of scale, of massing, he'll make the buildings somehow relate to what's around them, he understands context.

[The original plan, announced in December 2003, albeit without a close-up of the arena and the buildings around it, which were the only ones fleshed out.]

The question is, for me, is he going to be able to deal with the things that traditionally developers might not let him play with. For example, the social organizations of the apartments inside. The relationship of the project to the context around it, in terms of the ground plan. I think Frank comes out of a tradition, in terms of urban planning, that in a lot of ways is very conservative. He's never built on this scale before. And I think he's now getting into a kind of unfamiliar territory, in terms of the scale he's working with. One of the things I think happens when you're working with developers is that, y'know, the kinds of architects they're used to working with--they come up with a scheme and what the developer does is, he takes a scheme, and then he builds it.

And a talented architect, all of the work happens between here and here. You start with an idea and then it's at that moment that you struggle with it, that you realize that you start turning it into something, then it takes on a life of its own, you have to kind of let it go where it's going to go. And the question is: can these architects operate that way in the context of a developer like Bruce Ratner, and to me that's really important, because if you're able to make that system work and change that system, then you start to really affect the world in a very important way.

Andersen on Gehry, Gehry on Brooklyn

In the 11/28/05 issue of New York magazine, in an article headlined Delirious New York, Kurt Andersen noted that the reason for hiring Gehry (right, photo from Columbia University web site) was in part political:

Ratner isn’t spending 15 percent extra on these new buildings simply because he wants to underwrite cool design. He understands that in Brooklyn, just as his quotas of apartments for poor people and construction jobs for women and minorities were ways of winning over key constituencies, hiring Gehry was politics by other means, sure to please the city’s BAM-loving chattering class. “The spirit of what you say,” Ratner agrees when I posit this theory, “is accurate.”

And Ratner acknowledged to Andersen the distinction Ouroussoff pointed out: "I have to blame myself [for the Atlantic Center mall]. I’ve been talking for ten years about trying to use ‘design architects’ instead of 'developer architects.'"

But would the buildings of Atlantic Yards project "somehow relate to what's around them," as Ourossoff suggested? Andersen suggested they might not, but it was worth it: The skewed, cartoony angles of the buildings, which range from 20 to 60 stories, would in one fell swoop create a second, sui generis Brooklyn skyline encompassing the familiar, phallic old Williamsburgh Bank Building. Note, however, that that July 2005 design below may be supplanted by a new one. [Addenda courtesy of Naparstek.com]

A couple of letter-writers to New York magazine, however, were more critical. Stuart Schrader wrote: Like Bruce Ratner’s previous developments in Brooklyn, the Atlantic Yards stadium complex is not going to seamlessly merge a new development with an existing and vital cityscape. It seems totally appropriate, then, that Bruce Ratner would choose an architect whose buildings are rootless, equally out of place wherever they are erected, always supplanting on-the-ground urban realities with whimsical promises of a future that never quite arrives.

And what does Gehry think? Speaking to an audience at Columbia University on October 31, he said he had succeeded in getting the developer to agree to scale back chunks of the project (note that I originally wrote, based on the Columbia News Service report below, that Gehry wanted the project scaled back but Ratner has not yet announced doing so); that Brooklynites expect only brownstone scale (not quite; the community-developed Unity Plan for the Vanderbilt Yard envisions high-rise buildings, though not 40-60 stories, like some at Atlantic Yards); and that he's "brought all kinds of people in" to help him get it right (that's admirable, but could some of those people be concerned locals?).

Columbia's news service reported:

While best known for his shimmering forms like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, and the Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, the Toronto-born Gehry, now 76, views himself as an urban planner, whose buildings should enhance their surroundings. "I'm a do-gooder," he said. "I see architecture as a service."

But as people in Brooklyn expect the borough to be all "brownstones and tree-lined streets," Gehry's project has met with opposition from the community. "You can't do that with a project of this size," he said, adding that he had asked the developer, Bruce Ratner, to scale back the project several times.

Meanwhile, he hasn't convinced Ratner to do something else: bring in other architects to design parts of the project, to ensure a variety of styles. "He wanted to be able to deal with one person, so he refused," Gehry said.

Faced with the challenge of designing the entire project on his own, Gehry decided to develop a "design hierarchy," where several "iconic towers" will be surrounded by "background buildings."

But the dilemma, he said, is that the background buildings end up looking ordinary, like standard-issue housing projects. "Sometimes I think I should be less polite," he said -- implying that life would be easier if his buildings were all attention-getters.

"I'm very insecure about it," Gehry said of the Brooklyn project. "I've brought all kinds of people in to beat me up, because I want to get it right."

Tuesday, December 27, 2005

Atlantic Center mall vs. Atlantic Terminal mall: The Times can't tell (and why it matters)

A roundup article on post-Christmas shopping on the front-page of the Business Day section of today's New York Times, The Day After Christmas, Shoppers Take a Holiday, doesn't otherwise mention Brooklyn, but the photo depicts a man with four shopping bags. The caption: "Keino Bennet leaving the Atlantic Center Mall in Brooklyn yesterday."

A roundup article on post-Christmas shopping on the front-page of the Business Day section of today's New York Times, The Day After Christmas, Shoppers Take a Holiday, doesn't otherwise mention Brooklyn, but the photo depicts a man with four shopping bags. The caption: "Keino Bennet leaving the Atlantic Center Mall in Brooklyn yesterday."Except he's outside the brick-and-glass clad Atlantic Terminal mall next to the Atlantic Center mall and, at least in the picture in the print version, the cinderblock Site 5 of Atlantic Center is in the background, across Flatbush Avenue, with P.C. Richard and Modell's. (In the cropped, online version of the photo (right), there's no dispute: the only mall shown is the Atlantic Terminal. Note that in an earlier version of this post, I misidentified Site 5 as the Atlantic Center Mall. Both have similar coloring, quite distinct from the brick of Atlantic Terminal.)

Also, the man pictured is carrying at least two bags from Target, an anchor tenant of the Atlantic Terminal mall. Both malls are products of developer Forest City Ratner, but Atlantic Center (opened 1996) is much-reviled for disrespecting the urban fabric, while Atlantic Terminal (opened 2004) gets more mixed reviews.

As noted in Chapter 14 of my report, FCR head Bruce Ratner himself has criticized in Atlantic Center, telling the Times (Rethinking Atlantic Center With the Customer in Mind, 5/26/04): "Honestly, it isn’t beautiful. It’s not architecturally outstanding. It’s kept clean, and we do try and take care of it. It’s not as bad as a strip center in the burbs, I mean, but it’s not something that we would build again."

Others are harsher. Observed architectural historian and critic Francis Morrone in The New York Sun (ABROAD IN NEW YORK, 2/23/04): Atlantic Center Mall is the ugliest building in Brooklyn.

As for Atlantic Terminal mall, as noted in Chapter 10 of my report, a 5/22/05 Times Real Estate section article headlined The Underground Economy: Subway Retailing stated: The M.T.A. also worked with a private developer to turn Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn into an attractive mall with almost 400,000 square feet of retail space.

Now, Atlantic Terminal could not have been "turn[ed]... into an attractive mall" since it was built on empty land made vacant years ago after the historic Long Island Rail Road terminal was demolished. Atlantic Terminal more resembles the Manhattan Mall at Sixth Avenue and 33rd Street, which sits aboveground, with a subway concourse below. And The mall’s attractiveness is a matter of opinion. In a 4/25/05 New Yorker article, Rebecca Mead wrote (Mr. Brooklyn: Marty Markowitz—the man, the plan, the arena): The mall is an unlovely green-and-brown hulk bordering streets of brownstones, the shape of whose sloped roofs its own much taller roof grotesquely mimics.

The esthetic distinction between the two malls matters on another level as well, because the Atlantic Center mall may be torn down to build a new and higher-yielding development. It's not part of the Atlantic Yards plan, but it needs to be taken into consideration by urban planners. At the same time in February that city and state officials signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) regarding Atlantic Yards, they also signed an undisclosed MOU regarding two parcels of land. One parcel is Site 5 (now occupied by Modell's and P.C. Richard), to be replaced by a 430-foot tower as part of the Atlantic Yards project. The other is the Atlantic Center mall, which according to that second MOU--unveiled by Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn in August--offers 1.586 million zoning square feet for a mixed-use development consisting of residential development, commercial office space, and retail space.

According to page 3 of the MOU, if the arena project does not occur, Forest City Ratner would develop up to "875,000 square feet of commercial office space and up to 711,000 square feet of residential space on the Atlantic Center site." If Atlantic Yards does go through, the developer would subtract "328,272 zoning square feet of office, retail, and/or residential space." That would mean 1.26 million square feet. Given that Atlantic Yards, currently slated to be 9.1 million square feet, has been criticized as too big by even supporters like Marty Markowitz, the proposed project at Atlantic Center should be factored into the public discussion.

[Correction: FCR all along has had the right to build at the Atlantic Center site; the MOU would transfer a portion of the development rights to Site 5.]

Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, in its 10/28/05 response to the Empire State Development Corporation (a tenant at the Atlantic Center mall, by the way), commented that the upcoming Draft Environmental Impact Statement regarding Atlantic Yards must take plans for Atlantic Center into account:

In March 2005, ESDC, the City and FCRC announced the Memorandum of Understanding dated February 18, 2005 governing this project and entitled “Brooklyn Arena/Mixed Use Development Project”. There was another Memorandum of Understanding dated that same day entitled “ATURA Development Project” which was not announced. That second MOU appears to contemplate the transfer of development rights from the Atlantic Center to Site 5 and further development of the Atlantic Center. While the project description for this project does include some development of Site 5, it does not include the planned expansion of Atlantic Center. The DEIS must accurately describe what is contemplated in the second MOU and include the development contemplated therein as part of the project or at the least the cumulative impacts of the further development of Atlantic Center with the current proposal.

The Times has yet to write about this. In fact, the only daily paper to write about the second MOU was the New York Sun, in an 8/18/05 article headlined PRIVATE MEMO GUARANTEES RATNER SPACE. In the article, Ratner spokesman Joe DePlasco said that plans for Site 5 were disclosed at a 5/26/05 public hearing and in some local newspapers--true--but he said nothing about previous disclosure of plans for Atlantic Center. The Sun reported: As for the memorandum, a spokeswoman for the Economic Development Corporation, Janel Patterson, said that although it was never distributed publicly, it "has been available to anyone that requested it."

Note: there was no particular reason for the Times to shoot a generic post-Christmas photo outside one of Ratner's Brooklyn malls. In fact, the Times did shoot a second picture at Macy's at Manhattan's Herald Square; that smaller photo accompanied the Contents box on the front page of the main section. I don't suspect there was any intention to burnish the image of Forest City Ratner. It was likely the most convenient shot logistically for the assigned photographer. But if Times staffers were reminded that the developer is partnering with the New York Times Company on the new Times Tower, they'd have a heightened awareness of Forest City Ratner properties--for example, that 5/22/05 story mentioned above that praised the Atlantic Terminal mall should have named the developer, but it didn't. And they might identify the malls correctly. Because it matters.

Read your own clip file: the Courier-Life chain lets Roger Green explain it away

In an article published in several editions of Brooklyn's Courier-Life chain this week, state Assembly Member Roger Green discusses his potential run for Congress against Rep. Edolphus Towns. The incumbent Towns doesn't come off well--his spokesperson apparently declined to be named. But more curious is the newspaper's incomplete treatment of Green's ethical lapses:

While some have questioned Towns’ voting record, Green, if he decided to run, will be doing so with a checkered past.

In 2004, Green pleaded guilty to two misdemeanor counts of petty larceny stemming from billing the state for travel expenses that were already paid for from a prison-services company seeking state contracts.

As part of his bargain, Green escaped felony charges, which would have prevented him from standing for re-election. After his conviction, Green resigned his seat only to run again and regain it that same year.

“When I was re-elected [after the conviction], I received the largest vote of any African-American assembly member in the borough. I think my apologizing for what occurred embraces the narrative of African-American males in this society, which is about resiliency and human redemption,” said Green.

Green said he looks at U.S. Senator John McCain, who was part of the investigation related to the savings and loan scandal and later admitted mistakes, but went on to be one the nation’s most respected lawmakers.

But it was not just a question of resiliency and redemption. As the Courier-Life's then-Brooklyn Politics columnist Erik Engquist reported 6/14/04, Green's resignation was part of a plan:

Green would rather have not resigned at all, but he did so in a deal with Assembly Speaker Shelly Silver to prevent (or at least forestall) the release of the Assembly Ethics Committee's report on his misconduct, which would have prompted his colleagues to punish him.

The Assembly's refusal to release that report has been criticized by both editorialists and good government watchdogs, and Engquist's column pointed out that, while Green cited other lawmakers for ethical lapses, Green has a lot of trouble casting himself as a reformer.

One of the white lawmakers Green cited: Marty Markowitz. The New Yorker has reported that, when Markowitz first ran for Borough President in 1985, he pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor for failing to disclose a campaign contribution from a local businessman; he paid a nearly $8,000 fine, and performed 75 hours of community service. By contrast, according to recent press reports, Green paid $3,000 in restitution and $2,000 in fines, and was sentenced to three years' probation.

Another statement by Green deserves further analysis. One reason he received "the largest vote of any African-American assembly member in the borough" is that he faced no opposition in the Democratic primary--tantamount to election--and token Republican opposition. The New York Times explained on 11/2/04 (In District Lines, Critics See Albany Protecting Its Own) that it looked like cronyism:

While many New Yorkers might wonder about the fate of some candidates in today's election, Roger Green is not likely to be among them. Mr. Green ran without opposition in the Democratic primary and faces a little-known Republican rival as he seeks to return to the Assembly, completing a political comeback just months after he resigned from the Legislature in disgrace after pleading guilty to billing the state for false travel expenses.

Mr. Green's likely return to the Assembly is a textbook example, critics say, of one of the most brazen ways Albany protects its own: By carving up legislative districts to assure that incumbents face little or no opposition. In Mr. Green's case, the redrawing took place before his resignation, and after a significant challenge in a primary.

Mr. Green could have faced another formidable primary challenge this year from Hakeem Jeffries, a lawyer who made a vigorous but ultimately unsuccessful run against him two years ago. But this time around, Mr. Jeffries could not challenge Mr. Green, since his Brooklyn block was carved out of the 57th Assembly District, which Mr. Green represented.

"The district was cut out by just that one block," Mr. Jeffries said. "It's unfortunate that the dysfunctional nature of the Legislature in Albany allows politicians to slice and dice communities to meet their own needs."

The Times Union of Albany has produced the most thorough coverage of Green's lapses. The Albany County probation department concluded that Green was either of limited mental capacity or dishonest because he denied that he knowingly violated the law, the newspaper said. The probation officer called Green's story of why he submitted fraudulent reimbursement requests "very convoluted," according to a 3/25/04 article. Green's lawyer, without providing specific details, said facts in the probation report were "demonstrably untrue" and Green told the newspaper on 3/31/04, "It's not the first time a black man's intelligence has been questioned."

In a 12/22/05 editorial headlined "Enough, Mr. Green," the Times-Union decried Green's potential run for Congress: "So much for any sense of remorse... Next year, depending on what he runs for, [the people of Brooklyn] should vote against him for Congress or vote him out of the Assembly - anything to deny him of his shameless aspirations."

I should add that City Councilwoman Leticia James--now an antagonist on the Atlantic Yards issue--was Green's senior staffer during the period of time he billed the state for expenses he didn't pay for. She defended Green in the 6/4/04 New York Times, which reported: City Councilwoman Letitia James said, "The people in this community are still with him." Also, she told the New York Sun, in a 6/2/04 article: "There was no intent on his part to do anything wrong," said Council Member Letitia James, who formerly served as Mr. Green's chief of staff.

While some have questioned Towns’ voting record, Green, if he decided to run, will be doing so with a checkered past.

In 2004, Green pleaded guilty to two misdemeanor counts of petty larceny stemming from billing the state for travel expenses that were already paid for from a prison-services company seeking state contracts.

As part of his bargain, Green escaped felony charges, which would have prevented him from standing for re-election. After his conviction, Green resigned his seat only to run again and regain it that same year.

“When I was re-elected [after the conviction], I received the largest vote of any African-American assembly member in the borough. I think my apologizing for what occurred embraces the narrative of African-American males in this society, which is about resiliency and human redemption,” said Green.

Green said he looks at U.S. Senator John McCain, who was part of the investigation related to the savings and loan scandal and later admitted mistakes, but went on to be one the nation’s most respected lawmakers.

But it was not just a question of resiliency and redemption. As the Courier-Life's then-Brooklyn Politics columnist Erik Engquist reported 6/14/04, Green's resignation was part of a plan:

Green would rather have not resigned at all, but he did so in a deal with Assembly Speaker Shelly Silver to prevent (or at least forestall) the release of the Assembly Ethics Committee's report on his misconduct, which would have prompted his colleagues to punish him.

The Assembly's refusal to release that report has been criticized by both editorialists and good government watchdogs, and Engquist's column pointed out that, while Green cited other lawmakers for ethical lapses, Green has a lot of trouble casting himself as a reformer.

One of the white lawmakers Green cited: Marty Markowitz. The New Yorker has reported that, when Markowitz first ran for Borough President in 1985, he pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor for failing to disclose a campaign contribution from a local businessman; he paid a nearly $8,000 fine, and performed 75 hours of community service. By contrast, according to recent press reports, Green paid $3,000 in restitution and $2,000 in fines, and was sentenced to three years' probation.

Another statement by Green deserves further analysis. One reason he received "the largest vote of any African-American assembly member in the borough" is that he faced no opposition in the Democratic primary--tantamount to election--and token Republican opposition. The New York Times explained on 11/2/04 (In District Lines, Critics See Albany Protecting Its Own) that it looked like cronyism:

While many New Yorkers might wonder about the fate of some candidates in today's election, Roger Green is not likely to be among them. Mr. Green ran without opposition in the Democratic primary and faces a little-known Republican rival as he seeks to return to the Assembly, completing a political comeback just months after he resigned from the Legislature in disgrace after pleading guilty to billing the state for false travel expenses.

Mr. Green's likely return to the Assembly is a textbook example, critics say, of one of the most brazen ways Albany protects its own: By carving up legislative districts to assure that incumbents face little or no opposition. In Mr. Green's case, the redrawing took place before his resignation, and after a significant challenge in a primary.

Mr. Green could have faced another formidable primary challenge this year from Hakeem Jeffries, a lawyer who made a vigorous but ultimately unsuccessful run against him two years ago. But this time around, Mr. Jeffries could not challenge Mr. Green, since his Brooklyn block was carved out of the 57th Assembly District, which Mr. Green represented.

"The district was cut out by just that one block," Mr. Jeffries said. "It's unfortunate that the dysfunctional nature of the Legislature in Albany allows politicians to slice and dice communities to meet their own needs."

The Times Union of Albany has produced the most thorough coverage of Green's lapses. The Albany County probation department concluded that Green was either of limited mental capacity or dishonest because he denied that he knowingly violated the law, the newspaper said. The probation officer called Green's story of why he submitted fraudulent reimbursement requests "very convoluted," according to a 3/25/04 article. Green's lawyer, without providing specific details, said facts in the probation report were "demonstrably untrue" and Green told the newspaper on 3/31/04, "It's not the first time a black man's intelligence has been questioned."

In a 12/22/05 editorial headlined "Enough, Mr. Green," the Times-Union decried Green's potential run for Congress: "So much for any sense of remorse... Next year, depending on what he runs for, [the people of Brooklyn] should vote against him for Congress or vote him out of the Assembly - anything to deny him of his shameless aspirations."

I should add that City Councilwoman Leticia James--now an antagonist on the Atlantic Yards issue--was Green's senior staffer during the period of time he billed the state for expenses he didn't pay for. She defended Green in the 6/4/04 New York Times, which reported: City Councilwoman Letitia James said, "The people in this community are still with him." Also, she told the New York Sun, in a 6/2/04 article: "There was no intent on his part to do anything wrong," said Council Member Letitia James, who formerly served as Mr. Green's chief of staff.

Sunday, December 25, 2005

The Times corrects the "over the railyards" error--in the Real Estate section, at least

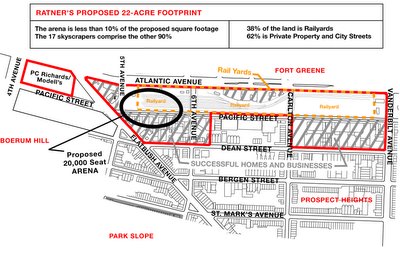

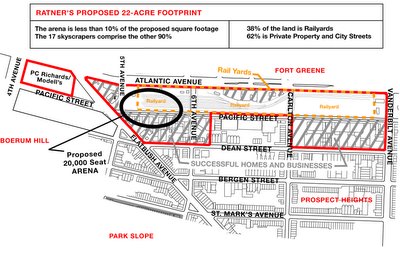

A Times Real Estate section correction printed 12/25/05: The "Living In ..." article last Sunday, about Prospect Heights in Brooklyn, referred imprecisely to a proposal by Bruce C. Ratner to build a nearby complex of shops, offices, housing and a basketball arena. It would indeed be built over the Atlantic Avenue railyards, but also on adjacent land now occupied by residences and businesses.

Indeed, precise description of the location is important, since the railyards occupy 8.3 acres of a proposed 22-acre site, as has been pointed out multiple times. The project also would require purchase of private land, the closing of city streets, and, most likely, the use of eminent domain--all unnecessary if the project were confined to the railyards. I'd also quibble with the description of the project itself, since, as I noted, the phrase "a sizable complex of shopping, offices, housing and a Frank Gehry-designed arena"--contrasts with the more accurate description in an 11/6/05 Metro section article: "essentially a large residential development with an arena and a relatively small amount of office and retail space attached to it."

Still, it's welcome that the Times--which generally corrects the most minute of errors--finally corrected this far more significant one. But will the Times now issue corrections for the same error? It previously occurred in John Manbeck's 11/13/05 op-ed (Forest City Ratner Companies' plan to build a sports arena surrounded by 17 imposing high-rise buildings on the Atlantic Avenue railyards) and then-architecture critic Herbert Muschamp's 12/11/03 assessment (The six-block site is adjacent to Atlantic Terminal, where the Long Island Rail Road and nine subway lines converge. It is now an open railyard.).

Given that previous correction requests regarding the above two errors have not yielded results, I'm not sure whether the correction printed today represents a change of policy or a sign of the Times's balkanization--it may be that the Real Estate desk is more willing to print corrections. Still, if the Times wants to remain consistent, the Manbeck and Muschamp descriptions should be corrected as well.

Indeed, precise description of the location is important, since the railyards occupy 8.3 acres of a proposed 22-acre site, as has been pointed out multiple times. The project also would require purchase of private land, the closing of city streets, and, most likely, the use of eminent domain--all unnecessary if the project were confined to the railyards. I'd also quibble with the description of the project itself, since, as I noted, the phrase "a sizable complex of shopping, offices, housing and a Frank Gehry-designed arena"--contrasts with the more accurate description in an 11/6/05 Metro section article: "essentially a large residential development with an arena and a relatively small amount of office and retail space attached to it."

Still, it's welcome that the Times--which generally corrects the most minute of errors--finally corrected this far more significant one. But will the Times now issue corrections for the same error? It previously occurred in John Manbeck's 11/13/05 op-ed (Forest City Ratner Companies' plan to build a sports arena surrounded by 17 imposing high-rise buildings on the Atlantic Avenue railyards) and then-architecture critic Herbert Muschamp's 12/11/03 assessment (The six-block site is adjacent to Atlantic Terminal, where the Long Island Rail Road and nine subway lines converge. It is now an open railyard.).

Given that previous correction requests regarding the above two errors have not yielded results, I'm not sure whether the correction printed today represents a change of policy or a sign of the Times's balkanization--it may be that the Real Estate desk is more willing to print corrections. Still, if the Times wants to remain consistent, the Manbeck and Muschamp descriptions should be corrected as well.

Beyond scale: the Times finally prints letters responding to its editorial, but ignores key criticisms

So, four weeks after the New York Times published a deeply-flawed editorial about Atlantic Yards (A Matter of Scale in Brooklyn, 11/27/05), calling for the project to be scaled down (by an unspecified amount), the Times finally printed four letters in response. I say "finally" because the Times City Weekly section usually publishes letters within a week or two.

The tally: three letters critical of the development, one in favor, but some key criticisms missing. The first problem is the headline: "Brooklyn's Railyards: The Fight Continues." It's not a fight about the railyard, it's about a 22-acre project that would include construction over the 8.3-acre railyard. How about "Atlantic Yards: The Fight Continues" or "Brooklyn Mega-project: The Fight Continues."

Lucy Koteen, an activist from Fort Greene, pointed out that the editorial ignored that "[t]he approval process bypasses all local oversight," even though the MTA land is only about one-third of the project. Koteen also noted that local residents "desire development over the M.T.A. yards that is fair and inclusive and has a city-led review process, rather than a developer-driven project that relies solely on well-oiled connections to the governor and the mayor for approval." However, unlike Daniel Goldstein's unpublished letter, Koteen diplomatically neglected to chide the Times for speciously suggesting that the residents of the area want the status quo.

Stuart Pertz of Park Slope, a former member of the City Planning Commission and a former consulting architect-planner to Forest City Ratner Companies, suggested that the Times let the developer off the hook:

Emphasizing "a matter of scale" in a debate over the developer Bruce Ratner's Atlantic Yards rather than character and quality exposes the public to a dangerous ruse.

A focus on scale allows a developer to own the development debate - letting the community steam and fret, and when the furor is exhausted, (reluctantly) reducing the project's scale to very much what the developer intended in the first place.

Peter Levinson of Windsor Terrace contended that Ratner may be gambling by planning 3,000 [actually, 2,800] market-rate condos, given other development in the area, and that taxpayers and politicians should think twice about funding it.

The only defense came from a Manhattanite, Jay Weiser of NoHo, a professor of real estate law at Baruch College. He wrote:

There is no more ideal place in Brooklyn (or even the United States) for a large-scale development like Atlantic Yards, which sits atop one of the densest mass transit hubs in the world.

Your concerns about scale are out of place. Atlantic Yards will rise over massive, empty railyards that have been an eyesore for a century.

Also out of place is your desire to replace Forest City Ratner Companies' market judgment on the appropriate mix of uses with your own. Why build commercial space in a marginal Brooklyn location when there's excess office space in Lower Manhattan?

In contrast, demand for housing is booming. Even if Forest City Ratner reduces the proportion of low- and middle-income units in the project, new market-rate units will add supply and reduce housing prices for all New Yorkers. We need to remove obstacles to build housing for New Yorkers.

Well, we're back to the distinction between "over the railyard" and "over and around the railyard." If the Atlantic Yards project were confined solely to the railyard, Weiser's argument would be stronger. His call to defer to Forest City Ratner's "market judgment" would hold more water if the company were not seeking subsidies and other benefits that distort the free market.

What's missing from these letters? How about criticism of the Times's willingness to overlook the costs of the project as a whole, or the effect of the most expensive arena proposed on those total costs?

The tally: three letters critical of the development, one in favor, but some key criticisms missing. The first problem is the headline: "Brooklyn's Railyards: The Fight Continues." It's not a fight about the railyard, it's about a 22-acre project that would include construction over the 8.3-acre railyard. How about "Atlantic Yards: The Fight Continues" or "Brooklyn Mega-project: The Fight Continues."